For decades, Sojun Mel Weitsman has been an anchor of the Buddhist community in the San Francisco Bay Area and beyond. It might well be, however, that even if you’ve been around the North American Buddhist world for many years, you know little or nothing about him. I’m pretty sure that Mel—or Sojun Roshi, as he’s called formally as a Zen teacher— is just fine with that.

The image of an anchor speaks of Mel’s style of dharma activity: it runs deep and steady, mostly below the surface of things, and its effects are often hard to see. This makes him less than a ready fit for Buddhist publications. His dharma talks, divorced from the quiet force of his presence, can lose much in translation to the printed page. He is not big on innovation, and he doesn’t go in for major projects or dramatic pronouncements. If he does attend a conference or seminar, chances are he is in the audience rather than on the podium. He is neither a mover nor a shaker.

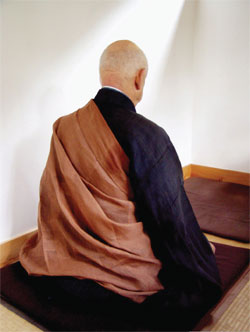

What Mel does is pretty much what he has done for more than forty years. In the morning, he gets up early and goes to the zendo (meditation hall) for zazen (sitting meditation) and morning service. He takes care of the Berkeley Zen Center, and he encourages his students. He spends time with his family. At night, he goes to the zendo for zazen and evening service. There’s not much there that’s newsworthy. Yet, if one investigates the matter further, it is clear that there is much more to the story.

For several years, we at Tricycle have tried to think of something we could do about Mel that would do him justice. Nothing we came up with seemed quite right. Then, last year, I received a copy of a small, privately printed book written for Mel on the occasion of his 80th birthday. The book, Umbrella Man, is a collection of tributes from Mel’s 20 deshi, or dharma heirs. Edited by Max Erdstein and Michael Wenger, it is an informal little gem of a book, not least because it so clearly demonstrates that as a teacher, Mel is best appreciated for the light that he has sparked in others.

Mel began Zen practice in 1964 with Shunryu Suzuki, the founder of the San Francisco Zen Center and Tassajara Zen Mountain Center and the author of the now classic Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. In 1967, Suzuki Roshi, with Mel’s help, established the Berkeley Zen Center, and two years later Mel was ordained as the center’s resident priest.

After Suzuki Roshi’s death, in 1971, the abbotship of San Francisco’s City Center and Tassajara passed to his dharma heir Richard Baker, and in 1972 a third temple, Green Gulch Farm Zen Center, was added to the rapidly growing SFZC community. Under Baker Roshi’s creative direction, the San Francisco Zen Center became a dynamic hub of Buddhist activity in the West. Across the Bay, at the Berkeley Zen Center, things proceeded at a more modest pace. But Mel was in the zendo every day, even if no one else was, and little by little the membership grew.

In 1979, the Berkeley Zen Center moved from its original location, on Dwight Way, to its present location, on Russell Street. Mel received dharma transmission from Hoitsu Suzuki, Shunryu Suzuki’s son and dharma heir, in 1984, and was officially installed as the Berkeley Zen Center’s abbot a year later. The zendo on Dwight Way was in the attic of Mel’s house, but at Russell Street, the members constructed a beautiful zendo building and housing for a small resident community. Today, the center has more than 150 general members.

In the mid-1980s, the San Francisco Zen Center community went through a long period of upheaval, at the core of which lay questions about leadership and power. This was initiated by events that many felt were part of a pattern on Baker Roshi’s part of misusing authority, and eventually Baker Roshi resigned as abbot. In 1988, during what was still a painful and confusing time, Mel was asked to assume the role of co-abbot of SFZC, and he agreed. For the next nine years, while continuing to lead the Berkeley center, Mel stepped up to help guide the San Francisco community. And when it was time to step down, he just stepped down.

In his introductory remarks to Umbrella Man, Hoitsu Roshi writes:

In Japan, we have a custom that celebrates when a person lives for eighty years. We call this Sanju. The “san” of Sanju means “umbrella.” We use umbrella in this case because the character for “eight” resembles an umbrella. When one reaches eighty, his character becomes more generous and broad-minded. His presence becomes like an umbrella, which can protect the people of the world from the rain and wind, the sufferings that arise in life.

The Buddha taught that “all constructed things are impermanent” and based his dharma teaching on this. “Impermanence” means that our bodies and minds, together with all things, will diminish and disappear. At the same time, it is precisely because of the impermanence that we grow and mature as years pass by. To grow old is to keep tasting life anew and to gaze at new scenery. It is to understand things that we didn’t understand before and to see things that we didn’t see until now.

I offer my heartfelt congratulations to Sojun Roshi as he celebrates Sanju. I really hope he will continue to be more and more healthy, that many disciples and Zen students will gather under his big umbrella, and that practicing together they will pass on the essence of Zen.

We at Tricycle join Hoitsu Roshi and the other contributors below in offering our congratulations to Sojun Roshi, the Umbrella Man.

—Andrew Cooper, Tricycle editor-at-large

Shosan Victoria Austin

I first met Mel at the Berkeley Zen Center, when I went there at the invitation of a friend. It was the mid-1970s, and I was looking for support for my Zen practice. Though the zendo was just a collection of sitting places around the edges of an attic room, the floor, the zafus, and the zabutons glowed with cleanliness. It felt cared for—welcoming—and intimate. After several visits, I came to meet Mel in dokusan [a formal, private interview with a Zen teacher]. In response to my question about practice, he said, “Just rely on zazen.” After that, Mel and I would meet for dokusan every so often. I began to notice that whenever I would go on and on, he would fall asleep. Often in the middle of presenting an emotional reaction to something that had happened, I would gradually notice him nodding. Sometimes he would open his eyes very wide, to try to stay with me. When the tone of my voice became authentic and fresh, he would completely wake up. Just last month in dokusan, more than thirty years after our first meeting, he told me, “Just rely on zazen.”

Ryokan Steve Weintraub

I was in the inner circle around Richard Baker at the San Francisco Zen Center, treasurer for five years and president for some years after that. It’s a little sad for me now, but during those years, I would say there was an unspoken disdain for this guy Mel Weitsman over in Berkeley. It was like, “We’re doing the real thing, this is where the real Zen is. The Zen capital of the universe is here. He’s doing something over there, and whatever it is, it’s not worth much.” I don’t remember anyone ever saying those exact words, but it’s quite clear to me that that was the attitude. I’m writing it now with some degree of embarrassment. To not recognize a jewel, it was just arrogance. It was the arrogance of much of SFZC’s leadership, including myself at the time. To be proper about it, I shouldn’t ascribe that arrogance to anyone else, but I can say that it was certainly my feeling. And I don’t think my feeling was unusual.

I really didn’t have very much to do with Mel during those years. Then, 4 or 5 months after everything blew up in 1983, my wife, Linda Ruth Cutts, and I went down to Tassajara, where we lived for a year and a half. Being at Tassajara really saved my practice life, because it reminded me of Suzuki Roshi’s way. For years I had grown increasingly discouraged with myself and, after the crisis, with Zen Center itself, which had been the focus of my life for 15 years. Returning to Tassajara renewed my inspiration.

I recall Mel coming down during that time. He was very warm and supportive to me, though he had no reason to be. I had harbored a haughty attitude toward him previously, but he didn’t hold it against me. Sometime during the following years, the idea for the two of us to study together came up, though I don’t remember who suggested it. Eventually Mel suggested we begin to study certain writings of Dogen that are generally related to dharma transmission, and I accepted his suggestion. This was tremendously generous of Mel. He didn’t have to offer his support in this way; he didn’t have to offer dharma transmission. He saw that it would be helpful to me, and that was enough.

Mel is steadfast. There is nothing fancy about him. When “big things” were happening at the San Francisco Zen Center, Mel followed his way, followed Suzuki Roshi’s way, teaching and practicing steadfastly, and modestly, at the Berkeley Zen Center. Once, Suzuki Roshi was giving a dharma talk and at a certain point, toward the end, he said, “This is a really good dharma talk. I should listen to this dharma talk.” I believe there is an important line of continuity, steadfast and modest, from Suzuki Roshi to Mel.

I’m tempted to say I don’t remember anything that Mel has ever said about dharma. That’s an exaggeration. But the point is that the core of the teaching I have received from him has come through how he is—how he is when he walks out the gate of the Berkeley Zen Center, how he is when he talks to me or talks to someone else. Sometimes, though, he’ll say something that really hits home. One time, at the beginning of one of our meetings, he asked how I was doing and I said, “Pretty wobbly.” He said, “Oh, you’re a wobbly buddha.” The Soto Zen way is not about achieving a particular state or experience; it’s about realizing and actualizing Buddha, including wobbly Buddha.

In Genjokoan, Dogen writes, “Those who have great realization of delusion are buddhas.” The place where you get to be Buddha, so to speak, is in delusion, and there’s plenty of that to go around. You get up where you fall down. You don’t get up somewhere else. It’s where you fall down that you establish your practice. Back years ago, at Tassajara, when I was feeling discouraged and confused, Mel helped me by being supportive and open and friendly. He assisted me in getting up where I fell down.

Jusan Edward Brown

Mel surprises me. The surprises are not unpleasant character traits haphazardly revealed or social gaffes carelessly displayed. No, instead, suddenly, in the midst of apparent plainness, sparkle flashes, and the brilliance is reflected in others. I find myself wondering, Where did that come from? Mel isn’t doing anything, yet others in the room are flourishing.

More than anyone else, I see Suzuki Roshi in Mel’s face. I tried for several years to be Suzuki Roshi: “It’s okay that you died,” I thought, “you can have my life.” But I just ended up abandoning myself. Mel is just Mel, and there’s Suzuki Roshi.

Mel surprises me. The miso soup he serves me looks so plain, and it’s so delicious. Calligraphy appears on the back of a rakusu [an abbreviated version of Buddha’s robe, given to students at jukai, the ceremony of receiving the precepts]—it’s beautiful like the magic of raindrops falling nowhere else. We’ve worked together with rocks at Tassajara and on Suzuki Roshi’s talks for the book Not Always So. It’s collaborative—my gifts rise to the occasion in his presence.

Daijaku Judith Kinst

Once I heard a lecture that described the ocean and its layers. The speaker told of the benthic layer, the deepest layer that is not affected by surface characteristics or more superficial tides. I immediately thought of my relationship to Mel. Ours is a con connection in the benthic layer. I think perhaps this is always true between teacher and disciple.

A friend of mine, a teacher in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, told me how her teacher understood her so well that he knew exactly what she needed, and when, as she developed. She wondered, was that true for me with Mel? I surprised myself when I said no, that in fact we had times of real struggle. But what I remembered, in that moment, was the clear sense that in the stillness of the benthic layer there was an unshakable connection that nourished my growth in the dharma. That kind of connection is exactly what I needed.

While I was his anja (personal attendant) at Tassajara, I had the closest daily contact with Mel and his teaching. Being anja for anyone was not my idea of what I wanted to do with my practice when I went to Tassajara. And it was, perhaps, the greatest gift of my time there. Learning the practice of mutually respectful service and absorbing embodied teaching silently broke down my ideas of who I thought I was and what I thought practice was and allowed a different understanding to form itself. Recovering from cancer treatment, thrown into a darkness I didn’t understand, the daily practice of zazen and ordinary contact with my teacher was the best medicine I could have had.

Once, on the way back to Mel’s cabin after a meeting, I was complaining about something. He turned to me and said, “You are being a spoiled brat.” Like a cold bucket of water. I knew he was right. In a way I had not seen before, I was circling around my own suffering. There was also kindness when I needed it, but kindness that was respectful of my commitment to the dharma. This was caring that was not confused with sentimentality. This was medicine that went directly to the root.

Dairyu Michael Wenger

I didn’t know Mel very well in 1988, when he was asked to be co-abbot of Zen Center. His primary practice place was to be City Center, while Reb Anderson would be at Green Gulch, and the two of them would alternate at Tassajara. The question of religious leadership was consuming the Zen Center community at the time. I watched Mel closely, and he welcomed the scrutiny. He seemed to accept whatever came his way. Soon I realized that I had a new teacher. I found that I could be straightforward with him and that we could disagree without jeopardizing our relationship.

Later, he helped me think through my questions about priest ordination. After an initial desire to be ordained, I didn’t see any reason to do it. I felt that my being a senior layperson made me more approachable to many students. I felt I understood this.

I grew up with little religious training. My parents were particularly suspicious of religious institutions. I was also very aware of how easy it is for the more narcissistic members of a community to gravitate toward leadership and for those with low self-esteem to defer to them. Mel suggested that I ordain and become the priest I wanted to become, not one that I was critical of. Whatever good reasons I had, I was resisting ordination, thinking that as a layperson I was better than the priests. But no form of practice is inherently superior to another. What a relief it was it was to stop resisting what I really wanted in my heart and let go of such arrogance!

Zoketsu Norman Fischer

It seems to me that the main characteristic of Suzuki Roshi’s teaching, and of Soto Zen, is faith in the practice and a steadiness and endurance to keep going with the practice no matter what. As Dogen taught so profoundly, the practice is the enlightenment. There is no enlightenment outside of practice. In the early days (and I know it is the same now) it was clear without anyone ever needing to say so that this was the value most encouraged by Mel. There was sitting every morning at 5 a.m., and Mel was there every day, always on time. Whether there was one person or two or three joining him (and there were seldom more than three or four) he was always there, sitting in his place at the head of the stairs, so that when you walked up the steep stairs to the attic you would see him first, just there, always there. Motionless and quiet. Dwight Way was a pretty busy street and there was sometimes traffic by the end of the morning session, but traffic or no traffic, whatever was going on, there was steady silent sitting. Every day, week after week, month after month. And by now, decade after decade. Though the location has changed and the years have sped by, I am guessing that the practice remains the same and the spirit remains the same: just to do the practice, to have faith in the practice, come what may. To be steady and to endure. To appreciate what is.

Not saying much, not explaining much—this was how it was in those days. There were no sesshins, no dokusan. Nothing special or spectacular. Mel gave, I think, a talk at the all-day sittings and maybe there was a weekly dharma talk, but these events were always themselves very quiet. Just part of the schedule. I always found them moving and encouraging, but they were not charismatic or complicated or exciting. Mel would speak pretty simply about our practice, very often bringing up sayings of the old Zen teachers or Dogen. I can’t really remember now much of what Mel said, but the general impression I had was of steadiness and wisdom and beauty. Conviction, but lightly held.

Chikudo Lewis Richmond Sojun

Mel Weitsman was my first teacher. I learned how to sit from Sojun; I first met Suzuki Roshi in the living room of Sojun’s house. Sojun said to me once, “Everything I have learned has been through patience.” As a generally impatient person, I took this as a great teaching and have never forgotten it; I also think he was just telling the truth about himself.

During a period when I imagined I had given up on being a priest, I came to Berkeley Zen Center for a ceremony and watched Sojun bow. That moment turned me; I saw in that bow something that awakened in me a path I thought I had forgotten. Within a few months, Sojun and I were doing transmission together.

After my transmission, I said to Sojun, “Remember, I’m not going to start a Zen group. That’s not what I do.” He didn’t say anything.

A few years later, after I had started a Zen group and it was thriving, I was again talking with Sojun and reminded him, with a little embarrassment, of my earlier comment. “I guess you must have known something back then that I didn’t,” I said.

He replied, “Oh, I don’t listen to what people say.”

Right.

What he meant was, “I don’t listen to what people say; I listen to what people say.”

Hoitsu Suzuki Roshi

Magnetic teachers who are good leaders tend to have a surprising, unpredictable quality about them. Sojun Roshi is like this. He has a side that is completely unlike a Zen master, and he also has a side that is like a Zen master. It can be said that he has an unpredictable nature.

As I see it, the side of him that is completely unlike a Zen master is the one filled with a very folksy, common humanity. He seems like an ordinary, amiable person and not a figure of authority as a Zen priest and teacher. In this way, I think he closely resembles his late teacher, Shunryu Suzuki Roshi. Like his teacher, Sojun is also a very natural person.

Nevertheless, once Sojun takes his seat in the zendo, sitting zazen facing in toward the room, his appearance completely changes and he has the dignity of Great Master Bodhidharma. His piercing gaze glares for an instant and is very penetrating. This is something that his disciples surely know well.

Zenki Mary Mocine

When I spoke to Sojun Roshi during my Mountain Seat [abbot installation] ceremony, I paraphrased King Lear’s upright daughter, Cordelia. I told him that I love him like potatoes love salt. I do.

Umbrella Man can be obtained from the San Francisco Zen Center Bookstore at 300 Page Street, San Francisco, CA, 94102, or by calling (415) 255-6524, or online at www.sfzc.org/bookstore.