In 1994, on one of his frequent trips through Southeast Asia, German-born photographer Hans Georg Berger first visited Luang Prabang, a remote mountain town in the republic of Laos. A renowned religious center and ancient capital of the “Kingdom of a Million Elephants,” the town is still famous for its many monasteries. Over the course of three years, Berger took more than 8,000 photographs there, many depicting the use of plants and flowers in Buddhist rituals and ceremonies.

Phra Meo, the Venerable Abbot of Wat Xieng Thong, a beautiful sixteenth-century temple in the old quarters of Luang Prabang, tells me that he considers flowers the most suitable offerings to the Buddha. Indeed, the frequent references to flowers in the sacred scriptures show that the Enlightened One enjoyed their presence in the monasteries and gardens of the Valley of the Ganges, where he taught and meditated more than 2,500 years ago.

In the town of Luang Prabang, rituals form the basis of everyday life both for the monks and the ordinary people. Every gesture and every object has a meaning and a history stretching back centuries, and many of the rituals are accompanied by flowers. There are, says Phra Meo, numerous customs, traditions, and other considerations about the kinds of flowers to offer for each occasion, and the ways of presenting them, that must be respected. First and foremost, one should be aware that to cut a bloom is to destroy a living thing. “The best flowers to offer are those that have not been picked at all but fall from the tree and are gathered in a cloth before they reach the ground,” he says.

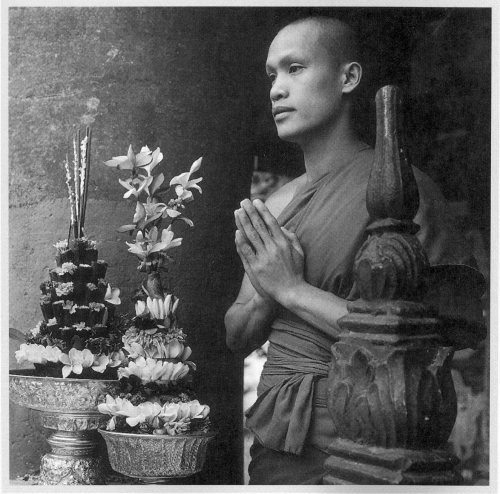

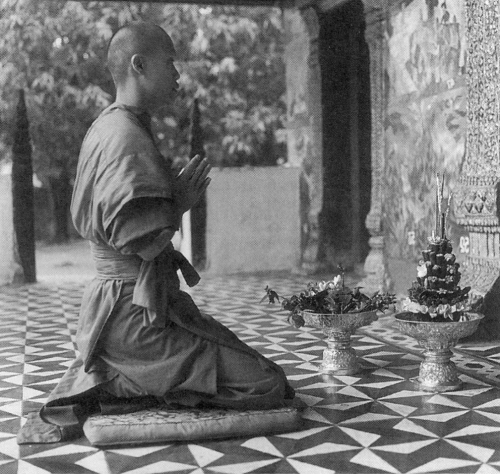

But of course not all the inhabitants of Luang Prabang will conform to such strict recommendations when they prepare their flower-offerings to the thirty-four temples of the town. The temples, lying close to each other on a narrow peninsula formed by the rivers Mekong and Khan, are the focus of the numerous festivities of the Laotian Buddhist year, where flowers play an important role. Blooms and leaves for the ceremonies are collected at precisely prescribed times of the day, and prepared to form elaborate objects in the shape of a stupa, or Buddhist reliquary. These are then presented on finely carved silver trays with fruit and sticky rice that the monks will eat after the celebration—thus giving laypeople the chance to gain particular merit.

Flowers of all kinds can be seen adorning the temples: old roses that have come all the way from southern China, exquisitely perfumed frangipani flowers (the symbol of the Lao nation), and different varieties of white and pink jasmine. Large branches of palm trees and banana leaves are also frequently used, as are cream-and-yellow marigolds, which found their way from South America to the banks of the Mekong—a legacy of European colonialism.

Flowers are used for the daily decoration of the sala, the open wooden veranda where the monks eat their meals, and frequently adorn other sacred places. For Bun Praveth, a festival in which locals evoke the Buddha’s previous incarnations by reading from the sacred scriptures, groups of laypeople organize a walk to the forests around the town. There they collect wildflowers, mostly orchids, which they bring in a colorful procession to the monastery to decorate the surroundings of theviharn, where the monks pray. On the first night of Bun Makha Busaa, when the monks record the first teachings of the Buddha to his disciples, hundreds of children and adolescents walk three times round the large wooden viharn of Wat That Luang, holding candles, incense sticks, and scented white frangipani and jasmine. Their palms are held together in the traditional Laotian nap, a gesture signifying peace and devotion. The flowers and candles offered by the children will, for one night, adorn the steps of a sacred stupa housing the relics of a pious king, Si Savang Vong.

The temples, or wats, are not only safe havens for abandoned animals but also places of conservation for rare or sacred trees and bushes. The leaves of one of these trees, the Talipot palm, or Corypha umbraculifera, have been used since ancient times as a medium on which to write sacred scriptures as well as texts of law and the extraordinary literature of the Lao, very little known in the West. The favored retreat for the monks’ meditation is a forest covering a steep hill to the right of the river Mekong. There, in ocher-brown robes dyed with natural annatto seeds, the monks sit under a carefully chosen tree, each performing a solitary exercise close to nature, sleeping on a bed of leaves protected only by a brown umbrella and mosquito net.

Contemplating a flower, says Abbot Phra Meo, is a way of reaching understanding. But the true Buddhist should be aware that the beauty of the flower is also a potential distraction—it is therefore important not to limit one’s considerations to the colors, forms and scent of flowers. Flowers represent impermanence—a central concept of Buddhism: they are sweet-smelling one day and foul and withered the next. Wat Xieng Thong, with its elegantly arched roofs, the facades decorated with golden sculptures and glittering mosaics, has a small enclosed garden, where pink and white old China roses bloom for most of the year. Looking out the garden from the small veranda in front of the room where he lives and sleeps, the seventy-six-year-old abbot says, in a confidential tone: “I like to look at these blooms, but I never smell them. I suppose it would be taking away something that is not freely given.”