Lama Drama

If Thinley Norbu Rinpoche has the severe philosophical and practical problems with Western Buddhist teachers, groups, and students that he claims to have, then it should be plain and clear that factual examples need to be given support to these very serious criticisms. If this chafing indeed exists as he says, then it needs to be openly aired, not further irritated by keeping it under cover (this is mainly the job of the journalist, not the interviewee). I would hope the spirit of open and honest inquiry is present whether you are interviewing a Tulku or a first-year student or a person hostile to the dharma. I find it difficult to believe that the interviewer didn’t ask the obvious “Who?”

Is Rinpoche commenting on Ole Nydal or Lama Surya Das or Stephen Batchelor? Friends of the Western Buddhist Order or the Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Buddhism or the New Kadampa Movement?

Is he talking about the students of my refuge lama, Tharchin Rinpoche, who has hosted Thinley Norbu Rinpoche at Pema Osel Ling in Santa Cruz?

His broad brush statements implying that all or most Westerners are “nihilists,” that they have no valid concept or practice of surrender, and that their expressions of compassion are condescending, are neither instructive nor enlightening.

I also believe that his definition of “nihilism” is terribly misplaced. As I have understood the Dalai Lama’s admonitions against nihilistic thought in Buddha-dharma, it has meant “the belief that there is no meaning or purpose to existence,” which has been a philosophical hurdle for some Westerners approaching the concepts of the ill-translated terms “emptiness” and “no-self.”

Instead Rinpoche uses the less common, archaic definition of nihilism, “the general rejection of customary beliefs in morality, religion, etc.” This is evident in the first line of his interview, “nihilism means not believing in any spiritual point of view.” He then spends the rest of his interview defending this skewed interpretation and develops it into an all-out attack on Westerners who earnestly seek to evolve teacher/student relationships beyond the no longer functional patriarchal models of divine infallibility. It has been my experience that most Western Buddhists embrace more of the traditional religious and cultural aspects of Buddhism than reject them.

No defense of incisive yet useful criticism of Western dharma practice is necessary—constructive criticism is more often invited than rejected. But if I have never before witnessed the last vestiges of archaic, patriarchal, religious politics scraping its collective fingernails down the slippery walls of history, I can surely say that I have now.

This type of “guru tirade” was very popular and effective in the 1960s and 1970s. I watched Yogi Bhajan, a former customs officer in Northern India, create an entire spiritual movement by insulting and condescending to his prospective Western students. And Americans, being the self-hating and disenfranchised people we believed ourselves to be, drove to him in flocks! As my younger and wiser friends say, “Go figure . . .”

Christopher Osel Dorje Moran

Topanga, California

Norbu Rinpoche, I am sorry if American Buddhists do not meet your expectations. We are the children of Socrates, Hume, Nietszche, Freud, Marcuse, and many others. Cognitive science, Western and Eastern philosophy, politics, and psychology all permeate our cultural existence. In addition, we have seen too many Russian, German, Chinese and other totalitarian systems that have caused mass human exterminations. We have seen the effects of heroin, crack, crank, etc., upon our cities, friends and family. Perhaps we are too distrustful of those who claim to have all the answers. However, blind obedience is not an option.

F. Zierold

Norbu Rinpoche attacks materialist minds and democratic minds as lacking in faith: “For men who have no faith, it is impossible to have pure dharma, like planting a burned seed in a field and expecting green shoots to come.”

But isn’t it that same Western mind that the teachers of Tibet are appealing to in order to bring democracy to their troubled land? The guru surely doesn’t expect Western Buddhists to cut themselves off from their roots, denying their scientific, materialist conceptions of reality. We are, after all, not in Tibet and the methods that enlighten the people in the East, with their long tradition of Buddhism and Buddhist lore, might not prove so successful for the more individualistic West. It seems to me that if a guru discovers that ‘his’ seed doesn’t take root, maybe the teacher should assume some responsibility for its failure. I wouldn’t plant the seed of an orange in the tundra and then complain if it failed to survive.

Michael Stone

Montreal, Quebec

Reading the Fall issue, I became despondent again about the state of the American mind in general. How is it we’ve managed to become virtual caricatures of spiritual practitioners and often even of human beings? I’m sure I’m not the only person who was very saddened by the apparent need for the “alms-rounds” in Olympia, Washington, and the “Buddhabus” tours. The sense of “American” Buddhism as performance art, drama therapy, or inspiration for home decorating ideas is pervasive in articles and ads. Perhaps a few people will take to heart the grounded essays of Thinley Norbue Rinpoche and David Frawley in the same issue.

G. F. Nair

Lummi Island, Washington

Thinley Norbu Rinpoche, in his diatribe, seems to equate faith with an unquestioning allegiance to “Buddhist lineage holders.” The West, from the Enlightenment onward, has engaged in a long and valiant struggle to separate the spheres of religion, science, and art, so that truth in any one of these realms could be pursued independent of the overweening influence of the other two. The dominance of religion and its principles over all three realms previous to the Renaissance forced scientists such as Galileo to recant what they observed about the physical world and artists such as Leonardo da Vinci to suppress their aesthetic expression. Most of the dignities of the modern era—including what Norbu Rinpoche refers to as “the modern superficial democratic idea of equal rights”—stem from this heroic differentiation. To simply dismiss this struggle as illusory and irrelevant, that is hubris. While it is sad that most of us have not integrated these realms into a truly holistic approach, or transcended them altogether, and that scientific materialism has come to dominate a Westerner’s perception of what is “real,” it is only logical that we should seek proof of legitimacy from any teacher in any realm. In short, the doctrine of divine right, whether granted to kings or gurus, is no longer in fashion. The West is justifiably wary of hierarchies, whether organic or imposed. To upbraid Westerners for questioning the “spiritual intangible qualities” of a teacher, even one of Thinley Norbu Rinpoche’s fine pedigree, appears foolish. Paul W. Rogers

San Francisco, California

Thinley Norbu Rinpoche’s Words for the West was a refreshing wake-up call. I’m happy to see his point of view join all the others that have been presented in Tricycle. What a treat to get a glimpse of his luminous wisdom mind.

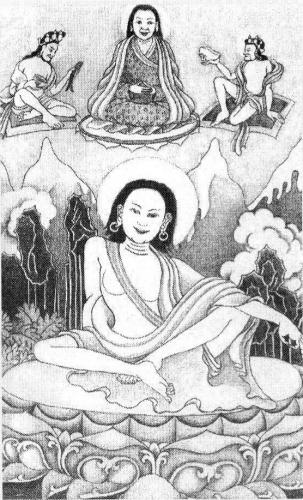

Thinley Norbu Rinpoche makes the point that belief and renunciation are essential, but some would like to bring that which they have renounced with them and make it a part of the path. This simply distorts and trivializes his view of Buddhist practice. One cannot let go while gripped by the nihilist fear of letting go.

Thinley Norbu Rinpoche also points out that surrender is essential. In the beginning it is to the Three Gems and the teacher, but ultimately in Vajrayana teaching it is to the nature of one’s own wisdom mind. While it’s reasonable in our overinformed society to have doubts, it is the teacher’s task to prevent the student from becoming a consumer of doubt and a prisoner of ego. Now more than ever we need the pure teachings of lineage holders like him.

Thinley Norbu Rinpoche stresses that devotion is the way one connects to the sangha and that this devotion is freeing rather than restricting. Freeing because the mind actually opens with devotion. Without devotion there is no teacher, student, or sangha.

Some would wish that Buddhism enter a hellish descent into intellectual utopianism. Abandoning our teachers will not lead to an enlightened future. Teachers like Thinley Norbu Rinpoche insure the continuity of the future by keeping the teachings of their lineage alive. The value of their wisdom mind is to tame confusion and to prevent Dharma from entering into discursive babble.

Nyingmapa tradition distinguishes between intellectual consensus and wisdom. Views based on political attitude are not spiritual. His Holiness Dudjom Rinpoche (Thinley Norbu Rinpoche’s father) told me, “Have these views if you like them, but don’t mix them with the Dharma.” While these views may be helpful to society, we shouldn’t mistake them for spiritual view, meditation, or action.

Les Levine

New York, New York

Some of the Tibetan lineages offer many instances in which the teacher “appears” to abuse the student, and Zen stories are filled with what might sound like verbal and physical abuse. It may indeed be lamentable that if the Great Marpa appeared among us today he would proabably be sued for abusing his devoted disciple Milarepa and villified by a righteous, unenlightened—and, by Thinley Norbu’s definition—nihilistic sangha. And after that, he might still be barred from teaching in the state of California by a self-appointed squad of dharma police.

The difference between what Marpa dished out to Milerepa and what Thinley Norbu dished out to us is that Marpa loved Milarepa. Love is the foundation of guru yoga. It is the experience of the guru’s capacity for unconditional love that opens the heart and allows for surrender to the guru’s compassion. Love is what distinguishes spiritual from military submission. Without love, what passes for guru yoga is another form of domination.

Thinley Norbu Rinpoche may have individual disciples for whom the traditional values of guru devotion are affirmed by their direct experience of his compassion. But for those of us who were introduced to him for the first time through Tricycle, trying to beat us into submission, or beating us up for our ignorance and delusions, feels a lot like guru devotion gone awry. By flaunting his views in arrogant and racist language, he (paradoxically?) reaffirmes the primacy of establishing a kind and loving context in which to pulverize our egos in the manner of supreme crazy wisdom masters.

In the years ahead it may prove to be true that, as the Rinpoche suggests, Buddhism in the West cannot survive the deterioration of the role of the guru and the importance of lineage. In that case, what a shame that he chose to take this opportunity to preach to the converted and leave most of us ever more mistrustful of the guru tradition that he cherishes and advocates.

Joseph Mitchell

Vancouver, British Columbia

Absolut & Relative

In “From A to Z,” Bill Alexander bemoans the self-loathing and low self-esteem he finds among AA members. He says AA implicitly blames alcoholics for their disease and helps to cultivate this perjorative self-judgement. I think Bill forgets that alcoholism is a family illness. Indeed, it is true that many alcoholics suffer from shame and a distorted sense of who they are. Shame, depression, and self-hatred are common characteristics among addicted and recovering folks. I think it comes from growing up in alcoholic homes or as co-morbid factors of the gestalt of addiction, and not from shortcomings in the AA philosophy or practice. As we get sober, we start to sort out these other issues and, if we are fortunate, get the right kind of help that we need, often outside of AA. In AA, I don’t feel blamed, but I do feel responsible for taking the medicine offered.

AA’s position that alcoholism was a disease and not a sin or moral defect was a radical breakthrough at the time the Big Book was published in 1939. Today alcoholism is listed in every medical textbook in the world as an illness, and the predisposition to this malady is usually inherited genetically. However, the medicine AA proposes IS moral: the twelve Steps takes us on the journey of transformation. The process begins with the first Step: the dropping of denial, the embracing of the reality of alcoholism and the acceptance of an ego deflation that allows us to go on with the journey. The Steps suggest a surrender to and guidance from a Higher Power, moral inventory, confession, restitution, and service toother alcoholics. Those of us who are thorough about this journey discover ‘a new freedom and a new happiness’; we don’t wallow in self hatred, but practice gratitude and acceptance on a daily basis as we grow along spiritual lines.

One more point: I wish Bill Alexander and the others quoted in your articles that spoke of their participation in Alcoholics Anonymous had observed AA’s tradition of anonymity. I was surprised to find out early in my sobriety that the practice of anonymity originated not as a protection of individual members (to shield them from discrimination in the outside world) but as a method to protect AA from its self seeking members. These folks would (and do) use their disease, the name of AA, the twelve Steps and the recovery process itself to promote themselves, through being an author, salesman, celebrity or entrepreneur, etc. I find it sad and disturbing that these AA members don’t heed AA’s simple call to humility through anonymity.

Anonymous

Portland, Oregon

I, like many, came to Buddhism after comparing it to twelve Step groups and found them wanting. Today, I simply cannot find Buddhism to be compatible with twelve Step Groups as I’ve experienced them.

Philip Kapleaus’s Three Pillars of Zen was the stuff of legend. It stated that as joriki, zazen concentration ability, was cultivated, that addictions would attenuate. Well, if this was true, twelve Step groups’ claim to being the “last route” for any addict must be bunk. I came to realize that this was true. If my nose itches, during zazen, and I’m able to not scratch it, how can that be different from wanting to have a drink during “rest practice” and not drinking? The more I practice, the more I realize that Buddhist practice, in and of itself, without focusing on drinking or not drinking, is sufficient to alleviate addiction. The fact that Twelve-Steppers were trying to coerce certain forms of religious behavior from me, under the threat of relapse was the straw that broke the camel’s back, for me. If we ask, without preconceived notions, “What is addiction?” and look at the scientific literature as one source for an answer, some interesting results can be found. Specifically the scientific literature states that what is most important in the maintenance of an alcoholic, sober, or moderative lifestyle is our belief about what the alcohol does. In fact, these beliefs are so important that there are numerous experiments that show that the “one drink, one drunk” belief about AA is bunk—self-described alcoholics will drink alcoholicly or not solely on whether or not they believe they are drinking alcohol. So whether or not one can stop alcoholic behavior or not is dependent on changing beliefs about alcohol. But how do we choose our beliefs? Buddhism teaches mindfulness and reliance on Buddha, Dharma and Sangha to find out what we experience as our true nature. It’s ours. We’re not powerless, and we’re not omnipotent. We’re perfect and complete, lacking nothing.

John M. Kowalski, Ph.D.

Vancouver, Washington

Some people have a familial biochemical variation in metabolizing ethyl alcohol: They lose control after just one drink. This variant is known as alcoholism. Although commonly called a disease it is not and was not so designated by the founders of AA, but if this susceptibility is repeatedly activated into a crescendo of months and then years of intoxication, alcoholism can cause many diseases. Such drinking also causes a degeneration of character and personality with resultant defects that not only damage life quality for all concerned, but also lead to repeatedly picking up the fatal first drink.

These defects are both the result of drinking and will lead to more drinking, but they are not due to the inborn variant that we call alcoholism, which in itself can be innocuous and need never lead to a drink. These are the defects that are reviewed and analyzed in “inventory” (“resentment is the number one offender”) and then admitted to a self, God and another human being—and for good reason, as has just been pointed out. It is these character defects and not the inborn biochemical variant which leads to the first drink and hence to the many diseases and death that can follow.

Finally, blame is not in this equation, and neither is disease if properly understood. The main function of the “disease concept” is to gratify those profiting from “treating” alcoholism, i.e., the rehabilitation industry in an era of HMOs. A lot of money changes hands, but the survivors are those who began and stay with AA.

Mistakes in describing AA can be fatal to those who use these mistakes as a reason not to enter the AA program, which would otherwise be lifesaving.

Donald B. Douglas, M.D.

New York, New York

Another Zen

I would like to respond to the article in your Summer 1998 issue about Joko Beck’s teachings of Zen. I agree with many of the key points that Sensei Beck makes with regard to what I call “worldly” or “therapeutic” Zen, or more to my point, non-religious Zen: neither little openings (kenshos) or big openings (satoris) are necessary for getting people to cope more constructively with everyday life; organized religion is always trying to change one into a better person; many people come to Zen or other belief systems in the hope of fixing up their lives; great satoris are not going to come to most people; the attempt at such a breakthrough is too often an ego or power trip.

However, I also belive that there is another Zen that is not the Zen of Sensei Beck. Her interview says that she has certainly separated from the way in which she was trained, and I suspect, though I may be very wrong, that this means a departure from traditional religious Zen.

Zen, from its beginning has been a religious phenomenon, and even though it was more often used for secular purposes, i.e., training samurai to be more efficient killing machines, it nonetheless has its roots in religion; by religion I mean the non-worldly or mystical renunciation of existence.

Mysticism is an awareness of a dimension of reality that is other than that of normal consciousness. It is the level that is reached though the Three Pillars of Zen: great faith, great effort, or what I prefer to call great courage, and great questioning or doubt. It has been my profound personal experience that a breakthrough, as defined in religious Zen, is necessary to achieve this mystical awareness. I do not wish to imply that this is a more authentic Zen than Joko Beck’s, just a different one. In fact, such a religious experience may have very little to do with enabling a person to cope more efficiently with everyday life, and it may even increase one’s ego, as Beck states. But, without this experience having occurred to me personally, I would not be anywhere nearly as satisfied with my life nor as tolerant of myself and others as I am now, as compared to my pre-breakthrough self.

Mysticism is an awareness of a dimension of reality that is other than that of normal consciousness. It is the level that is reached though the Three Pillars of Zen: great faith, great effort, or what I prefer to call great courage, and great questioning or doubt. It has been my profound personal experience that a breakthrough, as defined in religious Zen, is necessary to achieve this mystical awareness. I do not wish to imply that this is a more authentic Zen than Joko Beck’s, just a different one. In fact, such a religious experience may have very little to do with enabling a person to cope more efficiently with everyday life, and it may even increase one’s ego, as Beck states. But, without this experience having occurred to me personally, I would not be anywhere nearly as satisfied with my life nor as tolerant of myself and others as I am now, as compared to my pre-breakthrough self.

For many individuals, including myself, the Zen of Sensei Beck simply would never be satisfying. It is the mystical breakthough, or the Zen of faith, that led me to become a Zen monk and a Zen dharma teacher. It is this Zen that I teach. For some students who come to me it is the Zen that they seek; for others it is not. For the latter, possibly Joko Beck’s Zen would be preferable, and for this reason, I am grateful that there is more than one form of Zen.

Rev. Vajra Karuna

Los Angeles, California