Nonprofit organizations in the heart of Silicon Valley often marvel at the irony of not having websites to promote their work. Enter Nipun Mehta, a twenty-four-year-old former Sun Microsystems computer programmer who organized a network of over 350 well-meaning techies to create free websites for nonprofits on weekends and in their spare time. Mehta’s organization, CharityFocus, appears to be meeting its stated goal of introducing the pleasures of dana—the Buddhist practice of giving—to hundreds of computer professionals. Mehta says ChariryFocus is “an experiment in the joy of giving without any expectation of material gain.” Beneficiaries of CharityFocus include Sustainable Business Alliance, India Literacy Project, and California School for the Blind. CharityFocus has its own projects, including “Ask a Monk” (www.askamonk.org), a service for online seekers who have questions related to their problems in practice. Nipun, who sits every Tuesday at the Berkeley Buddhist Monastery, recently left his job at Sun to devote himself full time to ChariryFocus. He recently traveled ro the heart of India’s hi-tech beltway in Bangalore to help set up Tibetan Tech Training, an organization that brings technology education to exiled Tibetans.

Nell Newman learned to fish and garden with her dad, Paul Newman, and became deeply involved with the sport of falconry at a young age. But when she was eleven, she learned that peregrine falcons were facing extinction from the use of DDT. Nell is now using her time and her father’s good name to change the face of chemical-based food production, one pretzel at a time. Nell is head of Newman’s Own Organics, which she started in 1993 with longtime family friend Peter Meehan. Her idea was to make money for activism by forming a profitable organic food company. “Corporate farming is unsustainable,” she explains. “Soil is depleted, crops and fields are sprayed with poisons, workers are made sick by chemicals, and the government subsidizes it.” Organic farming helps reduce use of pesticides and herbicides, and generates an income stream for nonprofits that fight for the environment. Soon after starting the business, Nell did a few meditation retreats, at Valleciros, New Mexico, and at the Insight Meditation Center in Barre, Massachusetts. A vipassana practitioner, Nell is also an avid surfer; she considers surfing “meditation in action.” With respect to social action, her style is not ro preach but to set an 100 percent organically grown, that people already like—pretzels, chocolate, chips, and cookies. Paul Newman donates 100 percent of his after-tax profits to charities and has already given more than $100 million to over 150 ecological and humanitarian organizations, including the Organic Farming Research Foundation, Predatory Bird Research Group, Habitat for Humanity, and Rainforest Action Network.

Gary Cohen‘s vipassana practice taught him how big a turning of the wheel would be required, and how much patience would be needed, to awaken people to the extent of exposure to chemical toxins that people suffer around the world. Cohen is a tireless campaigner for the right to be healthy and free from pesticides and unsafe medical practices, such as the use of mercury, PVC, and medical waste incineration, without compromising safety or care. He served as director of the National Toxics Campaign and the Military Toxics Project, and now is the co-leader of Health Care Without Harm. Cohen sees his job as “Buddhist work,” reminding people about the interbeing, or the inherent interconnectedness, of their inner and outer ecologies. “We suffer an incredible disconnect between the saturation of toxic chemical inputs in our environment and our personal health.” “What is cancer)” Cohen asks. “It’s what happens when a cell mutates and grows so aggressively that it cannibalizes other cells in uncontrolled growth. It is a mirror of the uncontrolled growth of our global consumer economy that is literally consuming everything in its path.” Cohen coauthored the book Fighting Toxics (Island Press, 1990), which provides a detailed guide to combating toxins in local communities, from toxic waste storage sites and incinerators to factories near children’s playgrounds and schools, where they are exposed to asbestos, pesticides, and medical waste incineration. Raised in the postholocaust generation of East Coast American Jews, Gary has expanded the Jewish reminder “never forget” to apply also to the amazing tendency of some corporations to objectify human beings to such an extent that they are rendered expendable. One of the many examples he points to is that Dupont sold CFC products for a full ten years after it became known that they destroy the ozone layer and result in people getting skin cancer. Another is the reminder that “Union Carbide assessed the costs of their accident in India at about sixty-six cents a share.”

“For a while I forgot that I’m incarcerated,” said Martin, 17, from East Los Angeles, whose felony trial is set to begin later this summer. “This is the closest I’ll ever get to a church.” Martin has been enjoying a meditation demonstration from “the motorcycle monk” Carl Kohlhoff, an American ordained in a Vietnamese order who has taken to preaching the dharma to incarcerated

teens in the California prison system. Carl, also known by his dharma name, Rev. Kusala, studied with the late Ven. H. Ratanasara at the College of Buddhist Studies in Los Angeles throughout the 1980s and took his novice vows in 1994. Carl is the Buddhist chaplain for the University Religious Conference at UCLA and Director of the University Buddhist Association website. He was featured in several Los Angeles Timesarticles and in a report on the News Hour with Jim Lehrer about his work in Juvenile Hall. Known for often arriving on a motorcycle and beginning his lectures on meditation with a lesson on blues harmonica, Carl recently accepted a full-time position as the first Buddhist ride-along volunteer police chaplain for California’s Garden Grove Police Department. He keeps a laminated picture of Kuan-yin, the Chinese Bodhisattva of Compassion, in the side pocket of his bulletproof vest.

About the nature of his work over the past ten years at Zen Hospice Center in San Francisco, ex-government worker Louis Vega says: “I bring people their food, I change their diapers, and I watch them die.” The people receiving his care for his first six years were all dying from AIDS. Then the new protease inhibitor class of drugs turned AIDS from a fatal affliction into a manageable disease. “It was nice to see two men I cared for recover enough to walk Out of the hospice rather than be carried out,” remembers Louis. Now attending mostly to older people and victims of cancer, Louis feels his work connects him in a profound way to all of humanity. “Sad at times, when people die, but never depressing,” Louis remarks as he explains how caring for his

dying father awakened in him the deep satisfaction he feels from being with people as they face the end. He was already a student of Lama Lodre at Karma Kagyu when he received a letter from Zen Hospice Center asking for volunteers. Jumping at the chance to put his practice of compassion and impermanence to work in a practical way, Louis started working as a caregiver and never stopped. Residents of the hospice are cheered by Louis’ wry wit when he bids them goodnight. “Maybe I’ll see you next week, or maybe I won’t,” says Louis. “I could get hit by a car tomorrow.”

When the United Nations World Court of Justice finally declared in 1996 that nuclear weapons were illegal, it was the culmination of persistent efforts by many committed activists, including artist Mayumi Ada, founder and director of Plutonium Free Future. Mayumi has devoted much of her life to stopping plutonium trade. Her goal was to network with activists in the U.S. and Japan to publicize the fact that nuclear energy relies on the highly dangerous element of plutonium, and how vital it is to stop the hazardous transportation of this material across our lands and oceans. Mayumi credits her daily meditation practice, which includes mantra recitation, with not only rooting her to her “core” but also bringing forth her activism. She sits to deeply realize the two truths that compose her life: impermanence and interpenetration (interbeing). She is a firm believer in the power of prayer to guide her thinking and help her manifest her goals. Recently, Mayumi has focused on providing opportunities for young people living in Japan, and ro that end has started a fiveacre organic farm in South Kona, Hawaii, devoted to experimental farming in biodynamic and permacultural techniques. She coaches visiting Japanese university students interested in ecological activism in methods for growing their own food and medicinal herbs, such as kava, ginger, and gotakola (known as the Chinese memory herb). Investing themselves in the land in this way creates a spiritual and ecological base for their activism, or what Mayumi calls “sustainable activism.” Mayumi is also widely known for her magnificent and inspiring paintings, many of them colorful, mural-sized portraits of goddesses. Painting is another part of her spiritual practice in that “the work helps me understand who these goddesses are and what they represent.”

Annie Eichenholz lives In California with her husband and four children. She is also a Certified Hospice R.N. with more than fifteen years’ experience. Somehow she has found time to co-facilitate Volunteer Caregiver Training for Hospice and to educate health care professionals and volunteers in the Spiritual Care Program for Rigpa, a network of Buddhist centers around the world founded by Sogyal Rinpoche. Annie trains student caregivers in lovingkindness meditation, the compassion practices of tonglen, and the Essential Phowa, the principal practice of offering spiritual support to others at the moment of death (and a practice useful for one’s whole life). Annie has studied with Sogyal Rinpoche since 1981, and most of her work is based on his teachings and his classic bestseller, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying(HarperSanFrancisco, 1992). She was also influenced deeply by the book Facing Death and Finding Hope(Doubleday, 1998) by Christine Longaker, founder of the Spiritual Care Program. But much of Annie’s work is also based on her considerable experience and her own practice. Perhaps not so ironically, Annie came ro her work of caring for the dying through her studies as a prospective midwife. “The whole birth and death thing goes hand in hand,” Annie explains. Since, as Annie points out, all the major religions teach that stabilizing the mind at death is critical, the time to start working on it is now. “Through meditation practice, I work toward becoming a presence that is warm, loving, and compassionate, not only to patients but to my family and co-workers as well. The work, in turn, helps me open to suffering, and toward more profound compassion, and the clarity of thinking that goes with that,” says Annie. “Sometimes knowing what not to say—when to just be there in silence—is the greatest gift you can give.”

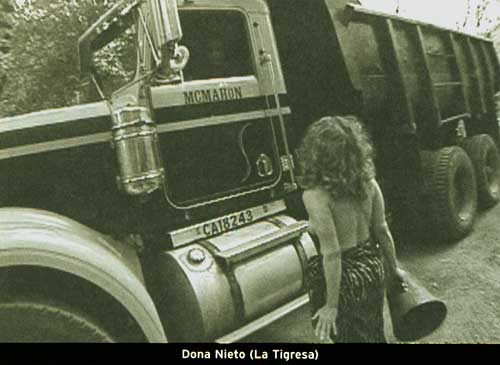

A logging truck in California’s redwood country suddenly comes to a gravelly stop while the driver stares ahead in disbelief. Dona Nieto, who goes by the name “La Tigresa,” has stepped into the road and removed her faux tiger skin sarong. She brings what she calls “Goddess-based, nude Buddhist guerrilla poetry” to the eco-war zones north of San Francisco, where environmentalists are waging a desperate battle to stop the clear-cutting of ancient coastal California redwoods—some of the oldest living things on Earth. “I’ve changed some of these guys’ lives” says Dona, “but I’d like to change the laws, and I’d like to change history.” Speaking into a beat-up megaphone, La Tigresa shares with the loggers a vision of both her body and the dharma of our ecological interdependence with the giant trees. When La Tigresa, who practices both vipassana meditation and pagan ritual, stops a logging truck with her bare breasts—what she calls “a striptease for the trees”—she commits herself totally: mind and body, sensibility, and awareness of the world. Ecoactivists, including celebrities like Bonnie Raitt and Woody Harrelson, lament the difficulty of drawing attention to the struggle, but this is where La Tigresa excels. Local newspapers, national media, the wire services, and such show hosts as Jay Leno, Rush Limbaugh, and Dr. Laura have taken notice of her bold tactics and the story of what may be the most serious ecological holocaust of our time. ▼