Burma is a police state. Make no mistake. You feel it the minute you arrive at Rangoon’s shabby, desultory airport, thronging with ill-equipped armed soldiers. Downtown, among the banyan trees, rust-robed monks, bicycles, trishaws, and Daihatsu trucks, billboards exhort citizens to crush internal and external foes. On the sidewalks, cheroot-smoking hawkers in longyis (sarongs) and sandals sell cheap combs, razor blades, and belts, or simply snooze in the sweltering heat beside the bundles on their mats. Old cars belch fumes, while between blighted British-built buildings wink shimmering gold-leafed pagodas. Consumer culture has barely penetrated here, and the currency, the kyat, is in a near free fall.

Burma is a police state. Make no mistake. You feel it the minute you arrive at Rangoon’s shabby, desultory airport, thronging with ill-equipped armed soldiers. Downtown, among the banyan trees, rust-robed monks, bicycles, trishaws, and Daihatsu trucks, billboards exhort citizens to crush internal and external foes. On the sidewalks, cheroot-smoking hawkers in longyis (sarongs) and sandals sell cheap combs, razor blades, and belts, or simply snooze in the sweltering heat beside the bundles on their mats. Old cars belch fumes, while between blighted British-built buildings wink shimmering gold-leafed pagodas. Consumer culture has barely penetrated here, and the currency, the kyat, is in a near free fall.

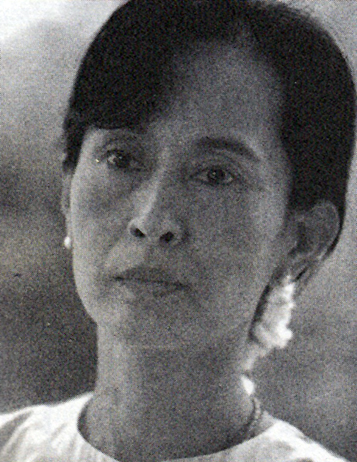

Burma—or Myanmar, as its current leaders controversially call it—is an ancient, picturesque land in eastern Indochina. Once an outpost of the British raj, it has been ruled by military force since 1962. It is a country curiously arrested in time, both charming and tragic. After the reformist National League for Democracy’s overwhelming electoral victory in 1990, the military blocked NLD leader Aung San Suu Kyi’s ascension to power; it closed down universities and imprisoned, killed, or banished many party members, intellectuals, and dissidents. Once one of the region’s most prosperous states, Burma now languishes in poverty and isolation, a pariah among nations, with a per capita income of $170 a year.

Ms. Suu Kyi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991 and is the daughter of modern Burma’s founder, Bogyoke Aung San. For six of the years since the annulled election she has been confined to her home in the capital, Rangoon (Yangon, in the rulers’ terminology). Unable to travel around the country or leave it without being barred from returning, she was denied a visit to her dying husband, Oxford professor Michael Aris, in 1999. In September of 2000 she was apprehended at gunpoint by government agents on the outskirts of Rangoon as she and supporters tried to leave the city; now she is once again under house arrest and remains incommunicado. Her case is but one of many: the week before I left for Burma in March, another NLD member, a writer, was sentenced to twenty-three years in prison.

Ms. Suu Kyi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991 and is the daughter of modern Burma’s founder, Bogyoke Aung San. For six of the years since the annulled election she has been confined to her home in the capital, Rangoon (Yangon, in the rulers’ terminology). Unable to travel around the country or leave it without being barred from returning, she was denied a visit to her dying husband, Oxford professor Michael Aris, in 1999. In September of 2000 she was apprehended at gunpoint by government agents on the outskirts of Rangoon as she and supporters tried to leave the city; now she is once again under house arrest and remains incommunicado. Her case is but one of many: the week before I left for Burma in March, another NLD member, a writer, was sentenced to twenty-three years in prison.

Burma’s military rulers, who consider themselves fervent Buddhists, rule by fear. Newspapers, television, and radio spew endless streams of propaganda, empty uplift, and xenophobia. Informers and spies sow suspicion among the populace. Telephone, fax, and Internet access are tightly controlled by the government, although CNN and NBC leak into the country, and the BBC and the Voice of America are broadcast in Burmese. Outside the country, several generations of exiles work to bring about democratic change.

Fewer than 160,000 foreigners make the trip annually to this land of mostly Theravada Buddhists, whose warmth and openness were remarked upon by nearly every visitor I encountered. The NLD has long called for a tourist and business boycott; in their view, money brought in serves only to prop up the military regime, though even some NLD supporters differ on this thorny issue.

Up-country, on the ancient archaeological plain of Bagan, among the more than two thousand exquisite Buddhist temples and stupas built nearly a millennium ago, the country’s present difficulties seemed remote. In the Shan highlands, where opium is still grown and people both practice Buddhism and worship nats(animist spirits), resilient tribal peoples endure illegal drug and amphetamine traffic, border squabbles with Thailand, and ecological depredations initiated by their own government.

“We’re tired of politics,” a Burmese intellectual told me one night in a monastery in the Inle Lake mountain region, out of earshot of the authorities, when I asked why popular support for Suu Kyi’s NLD party appears to be waning. “People are afraid.”

Yet the military reportedly has been holding secret talks with Ms. Suu Kyi in recent months to discuss the framework for a transitional administration. Whether the talks are merely meant to alleviate international pressure or whether they will result in some sort of power-sharing arrangement remains to be seen. The generals, should they lose power, may face charges for international human rights violations, not to mention the wrath of the their own people.

For now, progress is held hostage, and Aung San Suu Kyi, Burma’s elected leader, remains confined to her home, a virtual prisoner in a city with streets that bear her father’s name.