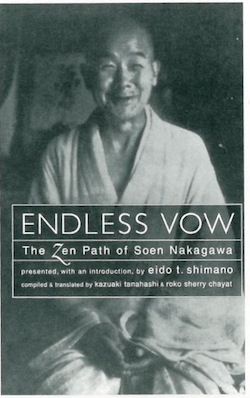

Endless Vow: The Zen Path of Soen Nakagawa

Presented, with an introduction, by Eido T. Shimano

Compiled and translated by Kazuaki Tanahashi and Roko Sherry Chayat

Shambhala Publications, Inc.: Boston, 1996.

179 pp., $13.00 (paper)

Soen Nakagawa Roshi (1907-1984) was a seminal figure in American Zen. For many American teachers and students, especially on the East Coast, it was his exemplary life and character that drew them into Zen practice and helped them persist when it proved to be so much slower and harder than anything promised by D. T. Suzuki. One of the first Zen masters who ventured—beginning in 1949—to these shores, Soen was abbot of Ryutaku-ji in Mishima, Japan, the New York Zendo in Manhattan, and Dai Bosatsu Zendo in Livingston Manor, New York. He was the dharma father of five well-known Zen masters, including the late Sochu Suzuki, who succeeded him at Ryutaku-ji; Kyudo Nakagawa (no relation), the present abbot of Ryutaku-ji, who founded the Soho Zendo in New York; and Eido Shimano, who founded Dai Bosatsu and the New York Zendo. Endless Vow, a remarkable and inspiring tribute to Soen, is a unique contribution to Zen literature. It includes a biography by Eido Roshi, several eloquent statements by former students, and a collection of Soen’s poetry and journals, translated by Kazuaki Tanahashi, in which his energy and faith are so vivid and concrete that the typically accepted conflicts between Zen and language seem to fall away.

Soen had a classical education that left him with an enduring passion for both Eastern and Western cultures. Goethe, Dante, Beethoven, and Schopenhauer figured no less significantly in his teachings and poetry than Bassho and the great Zen patriarchs. Ordained as a monk at the age of twenty-four, Soen displayed from the start an individuality and eccentricity that did not endear him to the Zen establishment. Zen, he said, was “fundamentally about the emancipation of all beings [but] unfortunately sealed in some square box called Zen.” At Ryutaku-ji, where he had gone to study with his teacher, Gempo Yamamoto Roshi, his dietary habits (at the time he ate no cooked food), his inclinations toward travel and solitary retreat, and his tendency to ignore the official monastery schedule and sit all day and all night led his fellow monks to complain to Gempo, suggesting he might be better off at another monastery. The same habits continued after Gempo, to the amazement of Soen as well as almost everyone else, made Soen his successor in 1951. Unlike other abbots, Soen insisted on taking his meals and sitting zazen with his monks, and he raised eyebrows among those who believed an abbot had “finished” his training by attending sesshin with Harada Sogaku Roshi at Hosshin-ji. No doubt it was the same independent spirit that led to his friendship with Nyogen Senzaki, the itinerant Zen monk who was the first resident teacher in the United States, and, later, on his many visits to this country, to his deep connection with American students, whom he found “more sincere” than the Japanese.

Soen had a classical education that left him with an enduring passion for both Eastern and Western cultures. Goethe, Dante, Beethoven, and Schopenhauer figured no less significantly in his teachings and poetry than Bassho and the great Zen patriarchs. Ordained as a monk at the age of twenty-four, Soen displayed from the start an individuality and eccentricity that did not endear him to the Zen establishment. Zen, he said, was “fundamentally about the emancipation of all beings [but] unfortunately sealed in some square box called Zen.” At Ryutaku-ji, where he had gone to study with his teacher, Gempo Yamamoto Roshi, his dietary habits (at the time he ate no cooked food), his inclinations toward travel and solitary retreat, and his tendency to ignore the official monastery schedule and sit all day and all night led his fellow monks to complain to Gempo, suggesting he might be better off at another monastery. The same habits continued after Gempo, to the amazement of Soen as well as almost everyone else, made Soen his successor in 1951. Unlike other abbots, Soen insisted on taking his meals and sitting zazen with his monks, and he raised eyebrows among those who believed an abbot had “finished” his training by attending sesshin with Harada Sogaku Roshi at Hosshin-ji. No doubt it was the same independent spirit that led to his friendship with Nyogen Senzaki, the itinerant Zen monk who was the first resident teacher in the United States, and, later, on his many visits to this country, to his deep connection with American students, whom he found “more sincere” than the Japanese.

In 1967, Soen suffered a near-fatal accident that left him with a piece of bamboo imbedded in his skull. Surgeons wanted to operate, but he refused. For the rest of his life, the excruciating pain he suffered as a result of this wound led to long periods of solitary retreat and increasing bouts of what Eido Roshi calls “unpredictable, erratic behavior.” “Practitioners in America,” he writes, “loved his spontaneity and viewed his actions as indications of his ‘crazy wisdom,’ but in Japan, people were not so understanding… It was clear to those of us who knew him well that he was suffering from depression during the last few years of his life, but his need for privacy, his shyness, and his pride wouldn’t allow him to admit it.”

Many of those who knew Soen, especially those like me who attended the New York Zendo during the period of Soen’s “depression,” will find such a description reductive and disrespectful. Like everyone else connected to the community, Soen was aware that allegations of sexual misconduct had been directed at Eido, so it is hardly unreasonable to assume that his “erratic behavior” was less a matter of internal psychology than the pain and embarrassment he felt about the behavior of his principal disciple in America. Eido’s reference to this period without any mention of his own role at the time seems disingenuous to me.

Still, such caveat seems trivial beside the portrait of Soen that emerges from his poetry and journals. At the age of twenty-seven, after a long fast in solitary retreat, Soen wrote the following pair of haiku a few weeks apart:

Flesh withering

Among myriad petals

I stand alone

Tears of gratitude

biting into a cucumber—

dharma flavor

The three conditions here described—aloneness, gratitude, and faith in the dharma—are Soen’s constant refrain. Like all great haiku, however, his are less description than embodiment of their subjects. And since his subject is always dharma, one cannot help but feel that these haiku are not about the dharma, but dharma itself. Present in these pages is a man for whom life itself was dharma, a constant reaffirmation of the vow that gives the book its title. “To my knowledge,” writes Eido, “no other roshi in Japan had Soen Roshi’s courage, faith, and enthusiasm for the dharma.”

“Why did you become a monk?” Eido asked him once.

Soen replied, “I so badly wanted to become a monk.”

“But why?”

“I so badly wanted to become a monk.”

It is worth noting that the mind from which these words sprang was not unsophisticated. Dualism and self-consciousness, not to mention the capacity to explain a matter so important as one’s choice of monasticism, were hardly unknown to it. This is a book about a monk who transcended such explanation, a man, finally, who took the dharma seriously. Think of it as medication, the perfect antidote to weakening of faith.