“When the iron bird flies, the dharma will come to the land of the red man.”—Eighth-century prophecy by Padmasambhava

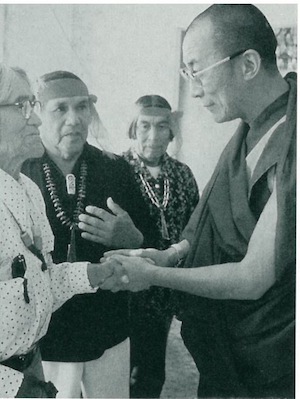

In the incongruous atmosphere of the Wilshire Hotel in Los Angeles, an extraordinary encounter took place in 1979. During the Dalai Lama’s first visit to North America, he met with three Hopi elders. The spiritual leaders spoke in their native languages. Delegation head Grandfather David’s first words to the Dalai Lama were: “Welcome home.”

The Dalai Lama laughed, noting the striking resemblance of the turquoise around Grandfather David’s neck to that of his homeland. He replied: “And where did you get your turquoise?”

Since that initial meeting, the Dalai Lama has visited Santa Fe to meet with Pueblo leaders, Tibetan lamas have engaged in numerous dialogues with Hopis and other Southwestern Indians, and now, through a special resettlement program to bring Tibetan refugees to the United States, New Mexico has become a central home for relocated Tibetan families.

As exchanges become increasingly common between Native Americans and Tibetans, a sense of kinship and solidarity has developed between the cultures. While displacement and invasion have forced Tibetans to reach out to the global community in search of allies, the Hopi and other Southwestern Native Americans have sought an audience for their message of world peace and harmony with the earth. These encounters have created a context for the activities of writers and activists who are trying to bridge the two cultures. A flurry of books and articles have been published, arguing that Tibetans and Native Americans may share a common ancestry.

The perception of similarity between Native Americans of the southwest and the Tibetans is undeniably striking. Beyond a common physicality and the wearing of turquoise jewelry, parallels include the abundant use of silver and coral, the colors and patterns of textiles, and long, braided hair, sometimes decorated, worn by both men and women.

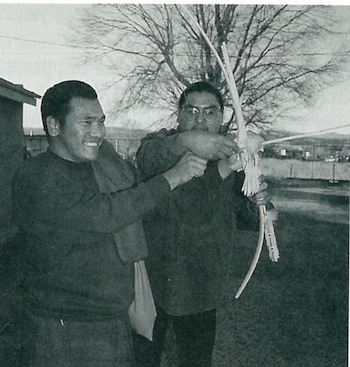

When William Pacheco, a Pueblo student, visited a Tibetan refugee camp in India, people often spoke Tibetan to him, assuming that he was one of them. “Tibetans and Native American Pueblo people share a fondness for chile, though Tibetans claim Pueblo chile is too mild,” says Pacheco.

Even before most Westerners knew where Tibet was, much less the extent of its people’s suffering, and almost twenty years before the advent of the Tibetan diaspora, cultural affinities between these two people were noted by Frank Waters in his landmark work Book of the Hopi (1963). Waters’ analysis went below the surface, citing corresponding systems of chakras, or energy spots within the body meridians, that were used to cultivate cosmic awareness. In The Masked Gods, a book about Pueblo and Navajo ceremonialism published in 1950, Waters observed that the Zuni Shalako dance symbolically mirrored the Tibetan journey of the dead. “To understand [the Shalako dance’s] meaning, we must bear in mind all that we have learned of Pueblo and Navaho [sic] eschatology and its parallels found in the Bardo Thodal, The Tibetan Book of the Dead, in The Secret of the Golden Flower, the Chinese Book of Life, and in the Egyptian Book of the Dead.”

Many Earth-based cultures steeped in a shamanic tradition share spiritual motifs (hence the broad comparison made by Waters). This could account for some similarities, such as Navajo and Tibetan sand painting, and cosmic themes found in Tibetan and traditional Pueblo dances.

But such comparisons hide the fact that there is no unified opinion among any indigenous groups, whether they are Tibetan or Native American. In the Southwest, for example, the Hopi and Navajo have distinctly separate cultures, religions and languages, yet they are often lumped together. Moreover, even among the Hopi, there is no single voice.

That, however, has done little to impede the promotion of a formal link between America’s own Earth-based spirituality and the unique and mythologized shamanistic Buddhism of Tibet. Since the publication of Waters’ books, some theories have claimed that the Tibetans and the native peoples of the Southwest both descend from common Mongolian tribes. Yet, even assuming that North America was originally populated by immigrants who crossed the Bering Strait some 20,000 years ago, common ancestry would not explain the similarities of more recent cultural artifacts. Another explanation posits a case of parallel, but unrelated, cultural evolution. This theory is certainly the greater possibility, even if it does not satisfy the somewhat romantic vision promoted by some Westerners of a “proven” ancestral link.

Not all third-party observers agree that a historical connection exists. Doug Preston, an author who served as the Dalai Lama’s press secretary on his 1992 visit to New Mexico, attended an important meeting between Hopi elders and the Tibetan leader. According to Preston, the meeting wasn’t the great reunion some had anticipated. “In my opinion,” he said, “the two great religious traditions did not have much in common, except on a general level. My impression is that the Dalai Lama is more concerned with the connection between humans, while the connection between Pueblos and Tibetans is irrelevant.”

Frank Korom, Ph.D., curator of the Asian and Middle Eastern Collections at the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, has researched how Tibetan iconography has been appropriated by the New Age. After long-term interactions with the Tibetan diaspora, he concluded, “Tibet is not homogenous. And this is obviously true of Native Americans.” According to Korom, the popularity of the idea of a connection between Tibet and Native America is “a need for a perennial philosophy of cosmic oneness.”

Joan Price, a writer and artist who has documented many of the exchanges between Hopis and Tibetans, noted how difficult it is to compare the prophetic messages of the two groups, something that many use as evidence for their ancient bond. “They are both very secretive, with good reason,” she said. “Events have conspired in both cultures such that they have to communicate with a very alien world.” Because of a need to protect their culture, it is hard for outsiders to get enough information to make a true comparison.

But searching for literal parallels between the groups, some observers argue, ignores a real bond that can be found in their respective struggles to preserve cultural integrity. Drodrup Chen Rinpoche, a Tibetan who spent time with the Hopis in the 1970s, emphasized a more general spiritual kinship. “It is very difficult to say if there are similarities or not,” he said. “But this is not important. The important thing is that among these Indians there are still elders who have this special knowledge and special power and transmissions. They, and the Tibetans too, should believe in their gods and deities, or whatever the object of reverence, do their prayers and have devotion, faith and confidence.”

In a talk to the Unitarian Church in Santa Fe in 1987, Gomang Khensor Rinpoche said: “From what I have seen, both the Hopi and Tibetan traditions have the highest regard for spiritual matters, both as bearing on the condition of daily life and also on the long run.” That there would be a resonant connection between Native Americans and Tibetans represents a natural outgrowth of their similar histories of oppression. Polger Thondup, director of Friends of Tibet, a nonprofit organization founded by Tibetan refugees in Santa Fe, finds Native Americans more receptive to their cause. “It’s much easier for Indians to understand the Tibet situation,” he said. “Anglos don’t know what it’s like to be oppressed. Westerners can be skeptical of the Tibet cause, but Indians are a friendly audience.”

Indeed, when the Dalai Lama visited Santa Fe in 1991, leaders of the fourteen Pueblo Nations of New Mexico gathered to express their solidarity with the spiritual leader, and to lavish him with jewelry and gifts. In one incident, a Pueblo resident took a silver warrior band from his wrist and slipped it on the Dalai Lama’s arm. Embarrassed by receiving such a gift, the Dalai Lama was told that refusing such an honor would be insulting.

Addressing the Dalai Lama and the Pueblo leaders, one Indian spokesperson said, “Our prayers for the people of Tibet in their struggle to further their claim to their homelands and their sovereign rights will forever bind us spiritually. Their struggle has become our struggle. We will always offer and seek spiritual solace for our continued existence and that of the people of Tibet.”

Reflecting on the meeting with the Dalai Lama, Regis Pecos, Executive Director of the Office of Indian Affairs, said, “Both cultures have been subject to the worst policies conceived to destroy them. The common bond is the compassion you get from going through these experiences, and the knowledge that others should not be subject to the same.” He went on to note that meeting the Dalai Lama was an incredibly moving experience for himself and all the Pueblo leaders.

From a historical perspective, Tibetans and Native Americans can certainly swap stories of political repression. Both are indigenous groups who were displaced by the expansion of imperialist governments, and both find their political power weakened by divide-and-conquer policies. Moreover, Tibetans and Native Americans have seen their populations suffer near-genocidal reductions.

To some observers, reservations and Tibetan refugees camps in India bear an uncanny resemblance to each other. For Thondup, the difference is that Indians have trucks and TVs.

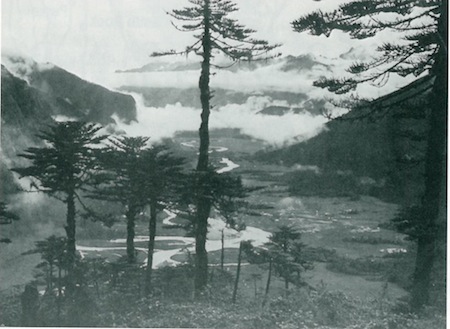

A person who has spent considerable time researching the similarities between Tibetans and Native Americans is Marcia Keegan, a Santa Fe-based writer and photographer who has spent the past twenty-five years photographing Southwest Indians. She is currently putting together a book of photographs that makes a visual comparison between the two cultures. “As I traveled and photographed throughout the Himalayas,” she said, “I saw many similar images, whether it be the architecture, the designs, the dances, the crafts, the people themselves, the turquoise, and of course the landscape.”

In addition to helping orchestrate the initial meeting between the Hopi elders and the Dalai Lama, Keegan, along with her husband, Harmon Houghton, also arranged and raised the money for a cultural exchange between the Tibetan Children’s Village in the Dharamsala refugee center in India, and four Pueblo Indian students from the Santa Fe Indian School. Pacheco, one of the exchange students, is now a freshman at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, where he has been involved with the Students for a Free Tibet Committee. Determined to be the first Native American to visit Free Tibet, he is also studying the Tibetan language.

Whether or not a historical connection between Tibetan and Pueblo people exists, the debate, say observers, is producing some positive results. According to David Dunn, an editor who collaborated with Joan Price in documenting the cross-cultural exchange, the “Hopi-Tibetan dialog is indicative of the kinds of problems and contradictions inherent in any indigenous or autonomous culture trying to maintain self-identity and tradition in the face of planetization.”

As Price observed, the process is like repeating a mantra. “You start saying a mantra, and very soon it gets complicated, and it puts you through different levels of thinking. Soon it becomes totally meaningless, which is also an aspect of the spiritual path, because eventually you just have to live each day carefully.”

The question of a unique and special relationship between Native Americans and Tibetans can lose sight of the more grounded assertion that indigenous groups in general share a similar cause. An affinity between the indigenous, especially in an era when more and more land-based cultures get displaced, is crucial. Whether its the Hopi, lowland Maya, or Kurds, there is a shared vision of a world in disrepair, and that in itself is sufficient evidence for a kinship that is likely to grow and expand among Tibetans and Native Americans.