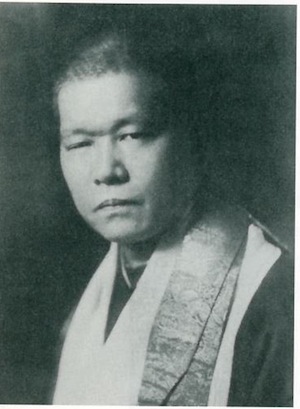

At the turn of the century, the United States became home to its first Zen master, Sokei-an Shigetsu Sasaki. Born in 1882 to a successful Shinto scholar and his concubine, Sokei-an first came to America as a student of the Zen master Sokatsu Shaku in 1906. Except for two return visits to Japan, he remained in the United States for the rest of his life, maturing into an artist and teacher with a distinctively American creative spirit.

As a young man, Sokei-an studied at the Imperial Academy of Art in Tokyo. Upon graduation in 1905, he was drafted into the Japanese Imperial Army and served on the Manchurian front. A few months after he was demobilized in 1906, he and his wife, Tome Sasaki, followed his teacher Sokatsu to the United States to help found the first Zen community in America, on a small parcel of land in Heyward, California. The community floundered, and in 1910, Sokatsu returned with his students to Japan. But Sokei-an remained behind, traveling east and supporting himself as a farmhand, art restorer, writer, humorist, and journalist.. In Greenwich Village he worked as a janitor and helped Maxwell Bodenheim translate poems by Li Po for The Little Review.

In 1922, after visiting Japan for an intense period of Zen study with Sokatsu, Sokei-an received inka, a Zen master’s seal of approval authenticating a student’s experience of awakening. He then returned to America, and during his second stay in New York began lecturing on Buddhism at the Orientalia Bookstore on East 58th Street, opposite the Plaza Hotel.

In 1929, with the support of Japanese and American friends, Sokei-an opened the Buddhist Society of America at 63 West 70th Street, a block from Central Park. From 1929 to 1941, the most productive period of his life, Sokei-an lived and worked at the Society. Two or three evenings a week, he gave sanzen and extemporaneous talks. During the day he worked on translations, including the Record of Rinzai and the Platform Sutra.

On December 7, 1941, the day the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the Society moved into new quarters at Ruth Fuller’s home at 124 East 65th Street. (Fuller, who was Alan Watts’ mother-in-law, subsequently became Sokei-an’s second wife as well as a priest at Daitoku Temple in Kyoto.) Six months later, after thirty-six years in the United States, Sokei-an was arrested by the FBI as an “enemy alien” and sent to Ellis Island – like many thousands of Japanese living in the United States. In a letter to Ruth he wrote, “The Island is shrouded in drizzling rain. Avalokitesvara weeps over me today. I am waiting for Alice in Wonderland to come.”

Sokei-an was transferred in October to Fort Meade, Maryland, but was released in 1943 after a vigorous campaign mounted on his behalf by several of his students. His arrest ended his “formal” teaching career, but he would continue to give sanzen until his death in 1945. After suffering a variety of complications due to high blood pressure, he passed away in his apartment, surrounded by his wife and students.

Sokei-an lectured on Zen and Buddhism in English. But he communicated the essence of the Buddha’s teaching and in his daily life by his presence alone, in silence, and in a radiance achieved through, as he once said, “nature’s orders.” In an essay published in Cat’s Yawn, a 1947 collection of his teachings and drawings, Sokei-an wrote, “I was initiated into Buddhism when I was still a boy. My age is now three score years. It was only yesterday that I came to understand what Buddhism is. Let me speak, lying on the floor with my yawning cat at my side, about the Buddhism which is my very self.”