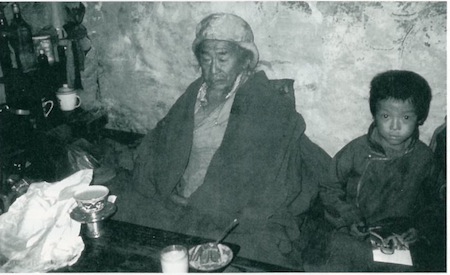

In 1990, I made a pilgrimage in Nepal to meet Cushok Mangtong, the Charok Rinpoche, a 106-year-old lama who lived in a mountain cave 15,000 feet above sea level. As my companions and I trekked over many days to his retreat, I decided to talk to him about what was happening to the earth, and ask him his advice about a world that was rapidly becoming dangerously poisoned.

After several weeks with Rinpoche, the day to ask finally came. Lama had never been away from the mountains and valleys of that region of Nepal and knew nothing of the modern world. But he was very curious. I talked about radioactive waste, with its 240,000-year life span before decaying into a “safe” level of radiation. I talked about how humans have become sick with cancers and other disease, and how we didn’t know what to do. He asked if there were people where we lived who were dedicating themselves to practicing for the benefit of others and said that even just one person practicing deeply will bring many blessings to the whole area.

Then he spoke of the earth treasure vases. Following a tradition that has been carried on for centuries on the Tibetan plateau, earthen vessels are made and filled with life-enhancing substances and then consecrated and buried in order to protect and heal the area around them. He told us that we should by all means get some and put them in many places. He told us to go next to Thangboche Monastery and ask the abbot there to make some for us.

“How can an earthen vase in the ground do anything to protect us against the kind of severe damage being done to the earth nowadays?” I wondered. But full of respect and willing to try anything, we set out for Thangboche.

The abbot offered to make the earth vases, and showed us some extraordinary relics he had saved—powerful medicines—to place inside the vases. Because of airport customs, it was better for them not to be filled and sealed in Nepal. Instead, they would mix the relics (which consisted of the crematory remains of great lamas) directly into the clay as they made the eight-inch-high pots, then we would fill and seal them ourselves back home. I asked if there was a special practice we needed to do accomplish this. “No, don’t worry about that,” he said. “We will consecrate them here. Just put them in the ground. They’ll do the work.”

Six years passed, and I had twenty-five earth treasure vases in a Nepali trunk in my home in Santa Fe, waiting to be put to use. I held back, unsure how to proceed, waiting for the “right” lama to come along and instruct us, waiting perhaps for the perfect Native American elder to tell us where they should go.

Finally, in the spring of 1996, northern New Mexico faced a severe drought, and forest fires raged across the Southwest. The skies were smoky and dark. The Lama Foundation had burned to the ground, the creeks were dry, and our gardens were dying. It was time to pull out the vases. At May’s full moon, a group of friends gathered to meditate and pray for rain. In the center of the circle was a bowl of water and four of the vases, one for each of the four directions. As if by magic, the first gentle rain in many months fell the next day.

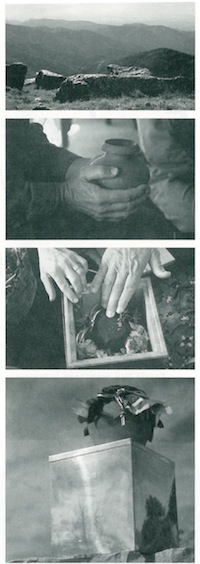

We began to meet regularly at the full moon, and we brought offerings to fill the vases: earth from sacred places in India, Nepal, Tibet, and the American Southwest, healing herbs and medicines, precious and semiprecious stones, rolled mantras, images of deities,dutsi (Tibetan powders made from relics), prayers, songs, even golden acupuncture needles—all kinds of things that were sacred to us. We brought grains and corn pollen, brocades and silk, and water gathered from around the world. Anything that had life-giving properties, a healing essence, or protective qualities. Month after month, no matter how many sacred objects we placed inside, there was always room for more. The vases began to take on a life of their own, full of energy and purpose. We honored the blessings of the lamas who had given us this tradition, and realized we were digging into our own cultural roots by placing them here.

By late fall, the vases were full and ready to be placed in the earth. It seemed natural to bury one in each of the four directions of the Rio Grande bio-region, embracing the watershed in a mandala of healing. One would go to the north, at the source of the Rio Grande above Creede, Colorado; another to the east on the highest peak above Santa Fe, the capital of New Mexico. A third would go to the south, near Brownsville, Texas, where the Rio Grande empties into the Gulf of Mexico, and a fourth would lie to the west in the Jemez Mountains above Los Alamos National Laboratory, the birthplace of the atomic bomb.

We sealed the vases with cork and beeswax, then decorated them with five colored silks, representing the five Buddha families, and sealed them with gold wax. We had made wooden boxes of fir, covered with copper to protect the vases in the ground, and we packed them inside with dried sage, lavender, rose petals, and juniper.

Before the winter snow came, we made pilgrimages to two of the four directions, north and east. This year the pilgrimages will continue to the south and west to complete the circle of protection for our small part of the planet. It’s just a beginning. There are still twenty-one earth treasure vases waiting to be filled and buried, and many other regions calling out to be stewarded in this way. As the lama told me, “Just put them in the ground. They’ll do the work.”