Miranda Shaw has a Ph.D. in Buddhist Studies from Harvard University, is the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship, and is currently Assistant Professor of Buddhist Studies in the Department of Religion at the University of Richmond. Her book Passionate Enlightenment: Women in Tantric Buddhism, which will be published this summer by Princeton University Press, clarifies the importance of women in the tradition of tantric teachings and practices. Tantric Buddhism is a nonmonastic, noncelibate strand of Indian, Himalayan, and Tibetan Buddhist practice that seeks to weave every aspect of daily life, intimacy, and passion into the path of liberation. Historians have long viewed the role of women in tantric practices as marginal and subordinate at best and degraded and exploited at worst. Shaw argues to the contrary. In addition to interviews and fieldwork conducted in India and Nepal over a two-year period, Shaw recovered forty previously unknown works by women of the Pala period (eighth through twelfth centuries C.E.) and has used them to reinterpret the history of tantric Buddhism during its first four centuries. Shaw claims that the tantric theory of this period promoted an ideal of cooperative, mutually liberating relationships between women and men while encouraging a sense of reliance on women as a source of spiritual insight and power.

This interview was conducted for Tricycle by Ellen Pearlman in New York City.

Tricycle: Are there certain overarching principles that one finds in the literature on tantric sexuality?

Shaw: Yes. The Tantras, or sacred tantric texts, make it clear that the purpose of the relationship is for the mutual enlightenment of both persons involved. It cannot be for the ego-gratification of one person. This purpose must be clear to both and agreed upon absolutely and explicitly by both. Another principle that could prevent the kind of exploitation that has occurred in the West is that the woman always takes the initiative in the Tantras. Always.

Tricycle: Can the man ask and the woman say yes?

Shaw: That would be a breach of form, because the initiative is in the woman’s hands. But if he does approach her, which is unusual, he must use an elaborate decorum that is set out in the tantric texts. He must be extremely respectful and use secret nonverbal gestures to communicate with her. He also looks for certain signs to determine whether she is a tantric practitioner, and he shows her that he is a worthy tantric companion by using these gestures and by rendering the forms of homage that are required of him. These forms of homage are laid out in the Yogini Tantras, what the Tibetans call the “Mother Tantra” texts. He has to prostrate to her, circumambulate her, and use a form of etiquette called “behavior of the left,” in which he stays on her left side when they walk together, takes the first step with his left foot, and makes offerings to her with his left hand. When they eat together he should always serve her first. These behaviors demonstrate that he does not regard this relationship as one of ego-fulfillment or self-service. He is showing that he is civilized enough and refined enough to become her spiritual companion and that he understands that this relationship will serve her.

Tricycle: And this is between student and teacher?

Shaw: No, this is between man and woman, whether the woman is the teacher or the man is the teacher or, more often, neither is the teacher of the other. The stories that come down to us include various types of cases. In tantric sexuality, the relationship is focused upon his offerings to her even though both partners are seeking to achieve certain yogic transformations. It is believed that they will bring their psychic states into resonance with one another and slowly lift each other, increasing and intensifying the energy that each has available for traversing the tantric path. So it is not the case that one person is gaining something psychically while the other person is being left behind. The partners must enter this realm, this experience of transcendental bliss, together.

Tricycle: How do they recognize each other? Shaw: First, they are looking for a tantric practitioner who understands the underlying principles of the relationship. A person who is new to the study and practice of Buddhism is not a potential tantric partner. One of the key qualifications is that both must have taken tantric vows, the vows that accompany Anuttara-yoga initiation. The vow, or samaya, is a commitment to the world view in which these principles are operative. The keeping of such vows will confirm the ability to keep a commitment, to maintain a relationship of profound, ultimate significance and import to both people and to surround it with the necessary integrity and secrecy.

Tricycle: Does that imply monogamy?

Shaw: It means impeccable integrity in their dealings with each other. For example, one partner could not be secretive about a relationship with someone else. One of the reasons for this—actually different from what we might expect—is that the partners are literally sharing their karma, their psychic resonance. They are communing on the most intimate level possible, mixing their spiritual destinies. That is one of the reasons it is called Karma Mudra practice: you are imprinting on one another’s karma. That is why you must choose a partner so carefully. If another person becomes involved, then his or her karma is brought into the equation, so it has to be with the knowledge and consent of the other person. The other person must at least be able to choose whether to continue or not, whether they want to interact with this quality of energy.

Tricycle: Can you say more about the formalities?

Shaw: The criteria for choosing a tantric partner are more stringent than those for selecting a mate or sexual partner. The principles that surround a tantric relationship are more thoroughgoing, because you are entrusting your spiritual growth to a relationship in which both partners will be undergoing profound yogic transformations. It is explicitly stated in the tantric texts that the woman has her own set of transformations that reflect the subtle anatomy of her psychic body, or yogic body, or what is called the vajra body. The man is instructed in how to make the series of offerings that relate to her increasingly subtle and interiorized experiences. As he approaches her, he makes offerings that please the senses, including kind, gentle words. It is said that he should not criticize the woman or speak harshly. He should be very agreeable, very pleasant, and make offerings to the buddha in her. She should also recognize the male buddha, the enlightened essence, in him.

Tricycle: Does she make any offerings?

Shaw: She makes no form of obeisance. This is to ensure that the balance of power in no way tips towards him. After he makes the outer offerings to the senses as he approaches her, the next level of offering is sexual pleasure. The tantric texts are very specific about this. He must be a person who is knowledgeable and skilled in that area. The texts describe this with great delicacy and beauty. He must be erotically skilled, an erotic virtuoso as well as a yogic virtuoso.

Tricycle: For the benefit of sexual pleasure?

Shaw: The point of giving her sexual pleasure is to awaken the bliss that she will then combine with meditation on emptiness in order to attain enlightenment. The instructions are extremely clear on that. Both partners must remind each other as the pleasure builds not to descend into ordinary passion or lose their mindfulness, because it is very easy to do that. So they may say mantras, or scratch or tap one another with their fingernails lightly to remind one another to maintain wakefulness. One of the reasons his virtuosity is so important is that as they begin to meditate on emptiness, the physical interaction must be very subtle and delicate in order not to distract her from her meditation on emptiness. At this point they both apply their understanding of emptiness to the experiences that they are undergoing. They start to deconstruct the bliss, the relationship, and the object and source of the pleasure as empty.

Miranda Shaw has a Ph.D. in Buddhist Studies from Harvard University, is the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship, and is currently Assistant Professor of Buddhist Studies in the Department of Religion at the University of Richmond. Her book Passionate Enlightenment: Women in Tantric Buddhism, which will be published this summer by Princeton University Press, clarifies the importance of women in the tradition of tantric teachings and practices. Tantric Buddhism is a nonmonastic, noncelibate strand of Indian, Himalayan, and Tibetan Buddhist practice that seeks to weave every aspect of daily life, intimacy, and passion into the path of liberation. Historians have long viewed the role of women in tantric practices as marginal and subordinate at best and degraded and exploited at worst. Shaw argues to the contrary. In addition to interviews and fieldwork conducted in India and Nepal over a two-year period, Shaw recovered forty previously unknown works by women of the Pala period (eighth through twelfth centuries C.E.) and has used them to reinterpret the history of tantric Buddhism during its first four centuries. Shaw claims that the tantric theory of this period promoted an ideal of cooperative, mutually liberating relationships between women and men while encouraging a sense of reliance on women as a source of spiritual insight and power.

This interview was conducted for Tricycle by Ellen Pearlman in New York City.

Tricycle: How would this apply to charges of sexual abuse against teachers involved with their students?

Shaw: I think it is very important that people become knowledgeable about tantric relationships and tantric intimacy. Once they become knowledgeable about it they will have something against which to measure any experience, any relationship they enter. At any stage they can evaluate, is this proceeding for mutual benefit? Is this proceeding for the sake of the enlightenment of both persons involved and for the sake of the enlightenment of all sentient beings? People can also apply this knowledge to the actions of Buddhist teachers. For example, one may hear about a teacher who verbally manipulated or emotionally coerced a woman to have sexual relations with him, was dishonest in his dealings with her, and displayed no yogic mastery in their relationship. This behavior can easily be seen to bear no resemblance to tantric practice.

Tricycle: What if two people who have not had any tantric initiations, which must be given by a lama or a teacher, want to practice tantric exercises anyway?

Shaw: This kind of information can be put to use by people who are not interested in gaining enlightenment but are interested in taking some of these methods from the East in order to enhance their sex life. Motivation is the dividing line between tantric practice and its more secular adaptations. I have a feeling that the people you might be describing would want to become a little knowledgeable about tantra to add new dimensions to their sex life.

Tricycle: So is this practice only available to lay Buddhists?

Shaw: It is available to those who have not taken monastic ordination. In the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism, for example, there are two routes one can take: one is thab-lam, the perfection stage practice with a yogic partner, and the other is dro-lam, the perfection stage practice without a partner for fully ordained monastics who do not want to give up their ordination or who are not ready to do this kind of practice. In many cases, in Tibet, the people who do not do tantric practice with a partner refrain because they feel they are not yet advanced enough. It is not that they believe that the monastic path is inherently superior.

Tricycle: Why do you think these practices have been so misinterpreted in the West?

Shaw: We in the West are at a very early stage of assimilation of Buddhism. We are very much where seventh century Tibet was when the Buddhist texts started streaming over from India. In India, these texts and teachings emerged slowly over hundreds of years, but when Indian Buddhism went to Tibet, all of the texts came together on the back of a yak, so they say. There was a lot of discussion, and confusion, because so many texts came all at once. Now in the West we also have received a wide variety of teachings, and we have to sift through them. There are so many Buddhist texts that it takes time for the ones that are pertinent to any given issue to be translated.

Tricycle: Do you find that any of these texts were suppressed because they were translated by men?

Shaw: In Tibet, for example, the tantric texts that I am talking about were expurgated in their canonical versions. In the earlier versions we find all the references to women and interactions between men and women intact. I find that in later canonical versions such references began to be expurgated because the translators increasingly were monks, so they had a vested interest in removing the references to women, the purity and glories of female bodies, and the grandeur of sexuality and sensuality in the religious context. Also in China these texts were expurgated and references to women were changed to references to men. I find that as these texts are translated into English, male translators typically render generic, ambiguous, and plural constructions into masculine terms and pronouns. That is very misleading. In different Tibetan versions and in the Sanskrit original where gender is specifically marked, in many cases I have found that what ends up in our English translations as a male reference was originally a female reference.

Tricycle: So this is a profound breakthrough. You are offering an English-speaking reader much more than just a “translation.”

Shaw: It is a paradigm shift because I have been working with different hermeneutical principles, a different approach to translation and interpretation. The philosophy that has held sway is that all religious texts are written by men, about men, and for men. I did not share that presupposition, particularly when I was looking at tantric texts that are clearly talking about something that is practiced by both men and women. I did not therefore assume that the texts contained only male experiences, insights, and points of view, and that revolutionized the way that I read the texts. Even though I had been trained for many years in the androcentric method of reading, I had a series of breakthroughs as I realized that the texts were talking about women, women’s experiences, embodiments, and sexuality from a female point of view, and religious practice from a female perspective.

Tricycle: Where will this new information take us?

Shaw: Academically it is going to open up a new field of research. Much more attention will be turned toward the origins of tantric Buddhism, the female founders of the movement, and the treatment of gender in tantric texts. I have worked with a certain number of texts, but a great deal of work remains to be done. Now that this door is open I am assuming a lot of researchers will take up this area of study.

Tricycle: How might this affect Buddhist practice in the West?

Shaw: People will no longer be able to use ignorance of the tantric teachings as an excuse for sloppy relationships and interactions. They can’t just say, Well, if it is a Buddhist teacher and it is sex, it must be tantra. I’ve had conversations with some teachers who have been accused of engaging in exploitative sexuality, and found in many cases that early in our conversation they might be cutesy and throw the word tantra about in a very offhand but suggestive way, hoping that I would let the topic drop and let that explain whatever it was that they had done. But as I started to ask them about specific texts and teachings and they realized that I was knowledgeable about the sources, they dropped all pretense of practicing tantra and immediately would confess that of course they had no knowledge of tantra and were not practicing Buddhist tantra. Teachers like these will no longer be shielded by the label of tantra, because we will know what this label means.

Tricycle: There will be a standard.

Shaw: Yes. Particularly because the classical tantric works that I have looked at—the Cakrasamvara, the Hevajra, and to a lesser extent the Guhysamaja, are the major Tantras that are used in Tibet. I also consulted theCandamaharoshana, which was one of the major texts in India and is presently one of the major Tantras used in Nepal. So I have consulted the major sources. I have not gone to minor, obscure sources.

Miranda Shaw has a Ph.D. in Buddhist Studies from Harvard University, is the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship, and is currently Assistant Professor of Buddhist Studies in the Department of Religion at the University of Richmond. Her book Passionate Enlightenment: Women in Tantric Buddhism, which will be published this summer by Princeton University Press, clarifies the importance of women in the tradition of tantric teachings and practices. Tantric Buddhism is a nonmonastic, noncelibate strand of Indian, Himalayan, and Tibetan Buddhist practice that seeks to weave every aspect of daily life, intimacy, and passion into the path of liberation. Historians have long viewed the role of women in tantric practices as marginal and subordinate at best and degraded and exploited at worst. Shaw argues to the contrary. In addition to interviews and fieldwork conducted in India and Nepal over a two-year period, Shaw recovered forty previously unknown works by women of the Pala period (eighth through twelfth centuries C.E.) and has used them to reinterpret the history of tantric Buddhism during its first four centuries. Shaw claims that the tantric theory of this period promoted an ideal of cooperative, mutually liberating relationships between women and men while encouraging a sense of reliance on women as a source of spiritual insight and power.

This interview was conducted for Tricycle by Ellen Pearlman in New York City.

Shaw: One of the things people can gain from my work is the realization that the problems we are facing are not new. We are not uniquely facing the challenge of creating a relationship, of pursuing enlightenment in the context of an intimate relationship. We are not the first ones to discover that men and women need to enter into right relationship with one another in order to gain enlightenment. It is not really viable for everyone to separate themselves out and isolate themselves in a monastery. That can create very problematic relationships between the feminine and the masculine. Avoidance itself can become an obstacle to enlightenment. We in the West are not the first to discover this, nor are we uniquely equipped to face this challenge. Many people claim that American women are bringing a new feminist perspective to Buddhism. I disagree with that. We may have done some Buddhist practice, obtained a college education, and have a feminist perspective but this does not mean that we have a more privileged perspective on femaleness than the many women who practiced before us. Those women practiced for many years; many of them were highly educated, and in addition to that, many of them were enlightened. They knew a great deal. We can learn from them. It is not just that we have something to teach Buddhism. Buddhism has a lot to teach us. It is somewhat contemptuous toward the Buddhist women of the past to suggest that we automatically know more than they. If they were enlightened then they knew things that we are still trying to discover.

Tricycle: But we sense that the daily context for them was one of sexist restraints.

Shaw: In the literature I have studied there were many women who were not dominated by men and who manifested complete freedom in their lifestyles. They were not dependent on men for their self-esteem or growth or for spiritual teaching. The women taught each other, and they taught men. They rebuked men, openly condescended toward men, and in no way conceded any superiority or preeminence to men. They were indomitable women.

Tricycle: Why do you think that got lost?

Shaw: It did not get lost. That has survived as a strand of the living tradition in Tibet and Nepal. The reason that in the West we have not recognized that aspect of the tradition is that the first thing we encountered was the most visible and impressive representatives of that culture, which are the monastic universities. These universities have existed in a relationship of competition with the yogic, noncelibate strand. Slowly these elements are becoming more visible to us. There were many, many enlightened women and female teachers in Tibet at the time of the Chinese takeover. Some of the people living today know their names and have their texts. They are often handwritten manuscripts that are kept by their students. I have confirmed the existence of some of their works, but their guardians would not show them to me, in part because the manuscripts contain the precious records of the visions and enlightenment of these women. Many of the women were self-styled, unconventional yoginis. Some of them went naked, some wore rags, some lived by the side of the road. Many of them traveled on perpetual pilgrimage. There was one woman in Tibet named A-tag Lhamo, which means Divine Tiger Woman. She united with many men. When she died, her father, who was a lama, said that every man who had united with her, who had sexual union with her, would never have a lower rebirth after that. They would either be reborn in a heaven realm or a pure land, because of the power of the blessing of uniting with her. That is just one example. Someone should collect these stories. Many are written in texts that are difficult to read. You have to have expertise in the language and you have to pry them away from their students. You have to prove yourself to be worthy to read them because it takes more than a scholar to translate a text which is talking about highly rarefied spiritual experiences. That is why their guardians rightfully will not entrust the texts to just anyone.

Tricycle: What did you have to do to gain access to the primary materials for your book?

Shaw: I had to gain the cooperation and help of a large number of yoginis and yogis. They were very conscious that by teaching me they were playing a role in the transmission of these teachings to the West. Therefore, one of the things that they were very concerned about, I could tell, was my motivation. They would question me at some length about what I was doing and why I was doing it, and they would question me about my dreams. In some cases they would not teach me until they had received a sign from the dakinis. That sign would usually be something in the sky, because the dakinis are sky dancers. Dakinis are both women and female spirits of exalted spiritual attainment and freedom. The teachers would look at the sky for unusual cloud formations or a rainbow or something out of the ordinary. When they received that confirmation, they would work with me while continuing to watch for signs. They felt that it was significant that I was a woman. These teachings have been guarded by female spirits through the centuries, and the teachers felt it was natural that the dakinis would choose to reveal the teachings to a woman at this time. So they felt that I had been sent or chosen by the dakinis to translate these teachings in the West. They believed that these teachings could not be revealed without the cooperation and blessings of the dakinis. That is not to say that there is anything special about the transmitter, the method that was chosen to transmit them. What is special is the transmission.

Miranda Shaw has a Ph.D. in Buddhist Studies from Harvard University, is the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship, and is currently Assistant Professor of Buddhist Studies in the Department of Religion at the University of Richmond. Her book Passionate Enlightenment: Women in Tantric Buddhism, which will be published this summer by Princeton University Press, clarifies the importance of women in the tradition of tantric teachings and practices. Tantric Buddhism is a nonmonastic, noncelibate strand of Indian, Himalayan, and Tibetan Buddhist practice that seeks to weave every aspect of daily life, intimacy, and passion into the path of liberation. Historians have long viewed the role of women in tantric practices as marginal and subordinate at best and degraded and exploited at worst. Shaw argues to the contrary. In addition to interviews and fieldwork conducted in India and Nepal over a two-year period, Shaw recovered forty previously unknown works by women of the Pala period (eighth through twelfth centuries C.E.) and has used them to reinterpret the history of tantric Buddhism during its first four centuries. Shaw claims that the tantric theory of this period promoted an ideal of cooperative, mutually liberating relationships between women and men while encouraging a sense of reliance on women as a source of spiritual insight and power.

This interview was conducted for Tricycle by Ellen Pearlman in New York City.

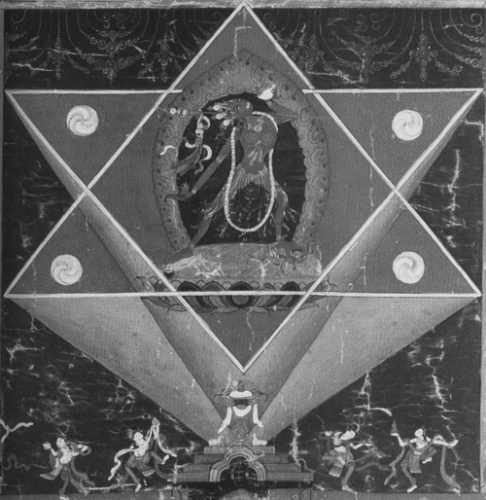

“What is sought in the yoga of union is a quality of relationship into which each partner enters fully in order that both may be liberated simultaneously. This level of intimacy is not easily achieved. Therefore, often a man and a woman would forge a life-long spiritual partnership. In other cases a male and female Tantric would go into retreat and practice together for a year or two to accomplish specific religious goals together. When the breath, fluids, and subtle energies of the yogic partners penetrate and circulate within one another, they produce experiences that otherwise are extremely difficult to generate through solitary meditation. The texts describe a complex spiritual interdependence, with an emphasis upon the dependence of the man upon the woman and his efforts to supplicate, please, and worship her. Their interdependence reaches fruition as they combine their energies to create a mandala palace spun of bliss and emptiness. Thus, the female and male partners in union both literally and figurativaly are ensconced within a mandala generated from and infused by their bliss and wisdom, which radiates from the most intimate point of their physical union. They use the energies and fluids circulating through one another’s bodies to become enlightened beings in the center of that mandala.”

From Passionate Enlightenment: Women in Tantric Buddhism