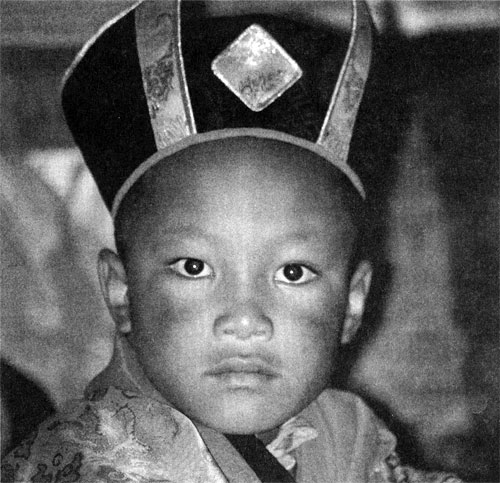

On June 17, 1992, a seven-year-old nomad boy from the steppes of eastern Tibet was installed as one of Central Asia’s great religious hierarchs. The child, Ugyen Thinley, was recognized as the Seventeenth Gyalwa Karmapa. His predecessors—the Guru Lamas of Kublai Khan and successive Mongol Chinese Emperors—had been virtual rulers of Tibet before the Dalai Lamas. Princes of an immensely wealthy theocratic establishment, they were buddhas in the guise of sacred magicians, high priests, and god-kings. The recognition of the last Karmapa was greeted with exultation and delight, rejoicing and relief—in Tibet, across the Himalayas, among Tibetan communities in exile, and by devotees of the Karmapa throughout the world. The ceremony itself was attended by thousands of Tibetans.

This event was doubly remarkable because it meant that a Karmapa once again presided at Tsurphu monastery, the traditional seat of the Karmapas in central Tibet. The Sixteenth Karmapa had been forced into exile in India during the 1959 Chinese invasion, taking along his followers, books, wealth, and ritual appurtenances, including his primary sign of office, his Black Hat, reputed to have been woven from the body hair of female buddhas. In 1966, the great monastery citadel of Tsurphu, located at an elevation of 14,500 feet in a desolate yet beautiful valley some fifty miles northwest of Lhasa, was destroyed by the Chinese army. A substitute seat was built at Rumtek, near Gangtok, in Sikkim, and the activities of educating tulkus and monks, blessing and comforting lay devotees, and proselytizing in the West, proceeded successfully under the powerful and benign gaze of the exiled Karmapa. But now the dharma of the Karma Kagyu school had returned to the place of its origin. Surely this was reason for all Tibetans to rejoice. Unfortunately, political controversy and faith-shaking doubt were to blight this event.

It had been ten long years since the Sixteenth Karmapa died of cancer in a hospital bed in Chicago, Illinois, at the age of fifty-six, and there had been increasing apprehension about the ability of his regents to discover the new incarnation. Lay pressure groups soon demanded quick action to identify a new Karmapa. Furthermore, the press had already reported accounts of disturbing events at the Karmapa’s seat of exile at Rumtek, in Sikkim. These reports indicated dissension about the identity of the new Karmapa among those appointed to administer the previous Karmapa’s temporal estate and spiritual parish. Factional intrigue had apparently reached the point of physical violence. Rumor and doubt were running rife among Tibetan and Western Karma Kagyu followers.

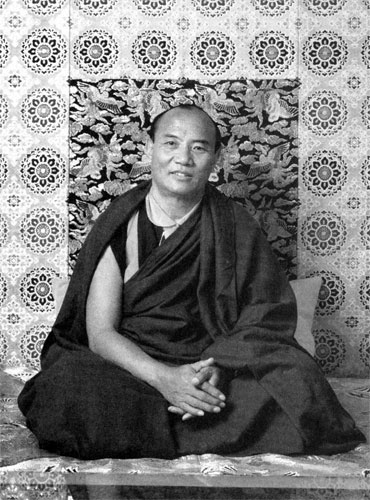

The Sixteenth Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje, had been a man of extraordinary charisma and personal power. In the twenty-three years of his exile he had established a flourishing monastic academy at Rumtek, hundreds of meditation centers around the world, and an international parish embracing individuals as diverse as Indira Gandhi and David Bowie who acknowledged his spiritual authority. His seat in the United States was established at the Karma Triyana Dharma Center in Woodstock, New York, and his spiritual authority was recognized by the disciples of the late Kalu Rinpoche and the disciples of the late Chogyam Trungpa, who hosted the Karmapa’s first visit to the United States in 1976. After his death, the Karmapa’s vast wealth in property and chattels was left in the hands of the Karmapa Charitable Trust, an organization governed by a board of trustees, while spiritual power was inherited by four young tulkus, who would act as regents until the Karmapa’s successor came of age at eighteen.

In the twelfth century, the First Karmapa had been the first Tibetan lama to adopt succession by reincarnation as a spiritual and temporal device by which continuity of his line could be assured. There was precedent in both India and Tibet for the recognition of particular realized beings taking rebirth for a special purpse. The Karmapas, spiritual heirs to the eminent succession of Indian and Tibetan tantric adepts from Tilopa and Naropa to Marpa and Milarepa, were the first to institutionalize the spiritual principle of a bodhisattva returning to samsara for the sake of all sentient beings. According to tradition, putative successive Karmapa incarnations were identified in a literary missive, a Letter of Intimation, written by the Karmapa, which could indicate precisely where his successor would be born. In general, this method proved successful down through the centuries, although there have been instances of conflicting interpretations and resulting rival candidatures.

Few literary indications were to prove so ambiguous, however, as that accepted by the four regents as the Sixteenth Karmapa’s Letter of Intimation. It consisted of a four-line verse that seemed only to exhort disciples to practice mahamudra—the highest form of yoga tantra—in order to expedite his rebirth. The lack of any further indication was the principal cause of the long failure to identify a Seventeenth Karmapa. There were political difficulties as well. In light of the Chinese record of treatment of high lamas—particularly the Panchen Lama, who had remained in Tibet as guardian of Lamaism when the Dalai Lama fled to India—was it wise to recognize a Karmapa born in a Chinese-controlled area? Surely the Chinese would seek to influence and control the child.

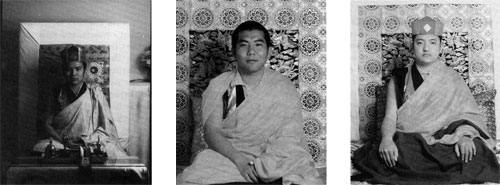

Inevitably, the personalities of the regents—the four young tulkus whose responsibility it was to recognize a successor to their Guru-Buddha—formed an important element in the scenario. The Shamarpa, a nephew of the Sixteenth Karmapa, has the dominant influence in Rumtek (the Karmapa’s seat) and also held temporary residence in Kathmandu, at the Swayambhu monastery of Subchu Rinpoche, as well as in Delhi. He is known for his ironic and realistic bent of mind and forward-looking perspective. Tai Situ, on the other hand, is more of the traditional savant and ritualist lama, highly competent and popular. He was based at his monastery at Bir, in the Kangra Valley in India. A rift—having its origin in their school days—now developed between these two most influential of the four regents and widened until the regency was deeply divided between the Shamarpa on one side and Tai Situ, with Gyeltsap Tulku, on the other; Jamgon Kongtrul, the fourth of the quorum, had long acted as mediator between the two sides.

To return to the sequence of events after the Sixteenth Karmapa’s death in 1981: the four regents had accepted responsibility for the identification of the Karmapa and in 1985 opened the Karmapa’s Letter of Intimation. This, however, gave them no substantial data to act upon. In 1990, the Sharmapa had a visionary dream indicating Lake Namtso, north of Lhasa, as the area in which the Karmapa had taken rebirth. He journeyed there, but could find no manifest sign. In the same year there was increasing pressure from Tibetan lay factions for an immediate discovery of the Karmapa. At this point, Tobga Rinpoche, General Secretary of the Rumtek Trust that administers the Karmapa’s multimillion-dollar estate, entered the picture together with a lay group based in Kathmandu that was known as the Thirteen Family Derge Group (Derge is the principal town of Kham). Fueled by the potent Tibetan rumor mill, various Byzantine intrigues were played out between the two factions. The most pernicious and divisive rumor was that a member of the Bhutanese royal family, supported by the Shamarpa, was the principal candidate to the throne. This rumor was to persist, much to the Shamarpa’s detriment.

In March 1992, Tai Situ requested a meeting of the regents in Rumtek. At this meeting, which Tai Situ seems to have dominated, the long-awaited breakthrough occurred. After prostrating thrice to the Karmapa’s throne, Tai Situ produced a second Letter of Intimation from a protection pouch that he claimed had been given to him by the Karmapa in 1981. This amulet (sunga) had been kept around his neck for most of the intervening years, a fact attested to by the sweat stains on the contents. His long failure to examine this gift from the Karmapa as a possible source of intimation, Tai Situ explained away as merely being a lapse of memory. The letter within stated explicitly the new Karmapa’s birthplace, his parents’ names, and other details—and it concluded with the Karmapa’s signature and seal.

The Shamarpa was not inclined to accept this letter as authentic and sought to keep its existence and contents concealed. Over the next few months, Tai Situ, overriding the principle of unanimity among the regents, publicized the letter’s contents and remained intent on having his candidate recognized. The Derge Group wrote to centers around the world promoting Tai Situ’s views. The pronounced failure of the regents to meet and obtain a consensus illustrated the acrimony that existed among them. The tension continued despite the tragic and most lamentable death of their mediator Jamgon Kongtrul in a road accident in India on April 26, 1992. His death has been followed by rumors of foul play, and both factions have claimed him as their erstwhile ally; while the rumors cannot be definitively substantiated, they will not go away. The delegation that Jamgon Kongtrul had been about to lead to Tibet (to locate the Khampa child mentioned in the letter) then departed to fulfill its task without him. The delegation succeeded in identifying the boy according to every last detail given in the letter.

The struggle among the regents reached its climax in an unseemly incident in Rumtek on June 12, five days before Ugyen Thinely arrived at Tsurphu. While Tai Situ and Gyeltsap Tulku were in Dharamsala claiming Kagyu unanimity in order to obtain the Dalai Lama’s verification of their candidate, the Shamarpa arrived in Rumtek and marshaled his forces. Speaking with strong personal feeling, he explained publicly his doubt regarding the authenticity of the letter, particularly questioning the handwriting and the signature. He had given a copy to forensic authorities in America, England, and Germany. Although nothing definitive could be said about the duplicate that he had submitted for testing, in the Sharmapa’s view Tai Situ was trying to foist an unproven candidate onto the Karmapa’s throne. The following day two busloads of Khampas (known for their ferocity as warriors) left Kathmandu for Rumtek with the avowed intent of convincing the Shamarpa of the error of his views. At the same time, the Indian government deployed an army unit to protect the Shamarpa at Rumtek. This unit arrived the next morning.

Later that day, June 12, Tai Situ and Gyeltsap returned from Dharamsala and immediately addressed the crowds gathered at Rumtek. They presented their case, celebrating the discovery of the Seventeenth Karmapa while defending their actions in the process of identification. When Shamarpa, accompanied by his army escort, decided to confront the situation at the monastery, he was greeted by violent opposition. It now appears that, in the intensity of the moment, disaffected monastery employees and Tibetans outraged by the Indian army’s involvement in this affair attacked the Shamarpa’s escort. During the fracas, an army captain and a member of the monastery staff sustained superficial injury. Tai Situ retreated upstairs and the Shamarpa returned to his quarters.

To the amazement of many devotees, this Rumtek farce displayed apparent human vanities and passions in a relationship between incarnate buddhas. What appeared to be samsaric emotion was evidently unfettered in an intense personal and political situation. To anyone familiar with the nature of Tibetan religious politics, however, this came as no great surprise. There had been rival candidates for the throne of the Sixteenth Karmapa, too, a struggle resolved only when the first choice—the son of a Gelugpa minister—died after a fall from a Tsurphu rooftop. And compared to some of the historic bloody struggles between all the Tibetan lineages, the pushing and shoving at Rumtek—however disheartening—showed restraint.

The conflict among the regents was satisfactorily—though only partially—resolved by a mediator, a “grandfather” lama respected by all parties. Ugyen Tulku of Bodhanath in Kathmandu, arrived in Rumtek and induced the Shamarpa to accept the Khampa boy as the principal candidate to the Karmapa’s throne. Ugyen Tulku tried to give the regents a placid perspective on events by assuring them that the authentic Karmapa would resolve the apparent deadlock. At this time, the Shamarpa chose to formally recognize Ugyen Thinley, while privately maintaining reservations. This recognition was subsequently confirmed by the majority of Kagyu tulkus.

The Shamarpa’s reservations were now to be held in the face of the Dalai Lama’s concurrence with the majority view. When Tai Situ and Gyeltsap Tulku went to Dharamsala on June 7, the Dalai Lama was in Rio de Janeiro attending the Earth Summit. In a faxed message they informed the Dalai Lama of the discovery of the second Letter of Intimation and its contents and of the existence of the child Ugyen Thinley in Kham.

They had left Dharamsala with the Dalai Lama’s faxed acceptance of their candidate. Later in the month the three regents visited the Dalai Lama in person to present their views. He confirmed unequivocally his previous decision, accepting Tai Situ and Gyeltsap Tulku’s evidence and identity of the Kham candidate and rejected Shamarpa’s private reservations. Because of the Karmapa’s political overthrow in the seventeenth century, the Dalai Lama possessed the final authority on the matter. He applied that authority judiciously and impartially.

In the days and weeks thereafter, fabulous stories of the birth and childhood of the Seventeenth Karmapa began to spread and the mythology of his birth was established. His conception had been marked by the cry of a hawk circling the tent where his parents lay. While pregnant, his mother had dreamed of three white cranes offering her a bowl of yogurt. She had also dreamed of Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhava, the eighth-century founder of Tibetan Buddhism) presenting her a letter that promised her a son with a long life. Just before his birth in a small nomad encampment on the plateau, a cuckoo (a holy bird) sang, and at the very moment of his birth the first rays of the morning sun entered the black yak-hair tent where his mother had labored. Three days after his birth the sound of a conch and cymbals resounded spontaneously in the sky for some hours and were audible to everyone in the area. Finally, when the party sent to bring the Karmapa to Tsurphu arrived, four suns were seen to arise over the important town of Chamdo, to the east.

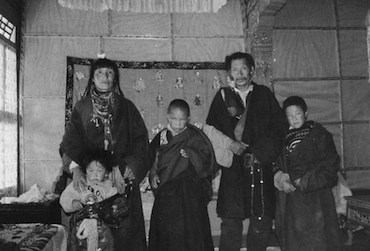

As indicated in the second Letter of Intimation, the Karmapa’s parents were cattle-herding nomads living in a black yak-hair tent on the plateau-steppes in the area called Lhathok. Lhathok was formerly a small kingdom, located to the north of Derge (in Kham). Unlike his predecessor, the Seventeenth Karmapa was born into a poor, uneducated family. He is the eighth of nine siblings, six sisters and two brothers, one of whom is older and one younger.

Indications that the mother was to bear a remarkable son were evident before the child’s birth. A local yogi, Jamyang Trakpa, who had accompanied Khamtrul Rinpoche to exile to Tashi Jong in India, on a visit back to Tibet, had left a robe with the family with the assurance that he would return for it one day. After his death, the family assumed that the newborn Ugyen Thinley was the yogi’s incarnation. The child was taken to the local monastery, Kaleb Gompa (a Karma Kagyu establishment), and there at the age of four was given monk’s ordination. He was not, however, recognized as any specific incarnation. Word spread of the existence of this remarkable child. Jamgon Kongtrul would probably have heard of him during his 1990 trip to Kham. Subsequently, a consensus upon the wisdom of recognizing this boy as the Karmapa could have been reached within the Tai Situ circle.

Few who have had the good fortune to meet the new Karmapa, who have seen the video of him, or have seen his picture, have doubted that the child is quite extraordinary and sufficiently remarkable to be such a high incarnation. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about him is his perceptivity, the insight that accompanies his sensory perceptions, and his existential discrimination in the situations in which he discovers himself, particularly evident in his communication with foreign devotees. He may be slow to verbalize, but his reactions are like lightning. At the present moment he appears to be a child who will be endowed with the qualities of a Gyalwa Karmapa by intuition rather than through study and intellect. However, he has yet to establish himself by a conclusive demonstration of his spiritual power, such as imprinting his foot in stone.

What, then, of the Shamarpa’s doubts and misgivings? First, a majority of regents, the Dalai Lama and most of the Karma Kagyu tulkus have accepted the Letter of Intimation and the candidate it identifies. For many reasons, there is a strong reluctance to discredit Tai Situ. However, the matter of the second Letter may still be disposed of by admitting doubt. It is conceivable that the handwriting and signature is not that of the Sixteenth Karmapa. Tai Situ’s well-intentioned discovery of the letter can be justified as a genuine attempt to give traditionally valid support to the obvious candidate. Discussion can then revolve around the wisdom of priests devising supports for the faith of the devout and the advisability of maintaining such supports that may have been acceptable in Tibet but are of questionable relevance in the West. Second, the possibility of multiple candidates and uncertain identity can be entertained in light of the notion that there is not one single Karmapa reborn in this world, but a multiplicity of Karmapas. The Sixteenth Karmapa himself once taught that he would be made manifest in eight hundred incarnations. The difficulty, then, is to determine the most suitable candidate to deal with the problems of the next generation. Some would advocate an academic Karmapa who could assimilate the concepts of modern physics and psychology into the dharma. Some would support a philosopher-logician; others an ascetic renunciate meditator (a Milarepa), others, a crazy yogi; and yet others, an able administrator. There is doctrinal precedent for the idea of multiple candidates.

Tai Situ believes he has discovered the fated incarnation in Ugyen Thinley, thereby satisfying the craving of devotees for an object of devotion in this lineage that leans most heavily on faith as a support to meditation. Still, the Shamarpa privately expects the discovery of a further Letter of Intimation or another candidate to be made manifest. This expectation is reinforced by the foreboding that the Chinese will not allow the present candidate to leave Tibet. A paranoid scenario for the future presents the Karmapa as a political pawn in the hands of the manipulative, imperialist, atheist Chinese. Others may consider an impressionable young Karmapa exposed to Rumtek politicians and fanatical Western devotees as the worst-case scenario. At least at Tsurphu he would be educated in a more traditional, congenial, and aesthetic ambiance, where he could obtain the extended meditation-retreat experience denied his regents by their international peregrinations. But the Chinese may choose to prove their professed religious liberality in Tibet by allowing the Karmapa to come and go at will. On September 27, he received his ritual enthronement at Tsurphu in the presence of many Kham Kagyu tulkus, thousands of devout Tibetans, a group of Western disciples, and with the support of Chinese authorities. The question of whether an exit visa will be granted him to permit attendance at a further installation at Rumtek, where he will take possession of his Black Hat, remains unanswered at this time.

Devotees watching from afar the tragicomedy played out by the regents in the last few months have been placed in a situation of intense meditative potency. Above all, they have been exhorted by the Sixteenth Karmapa in the first Letter of Intimation to practice mahamudra meditation, the cornerstone of many of the Kama Kagyu school’s spiritual accomplishments. Such a practice would support the nondual view in which the temptation to take sides and join the emotive fray can be avoided. The events described above would then appear as an illusory dance called “identifying the Karmapa” or maybe simply “a political folly.” Here is an opportunity to transform, through detachment, a political scenario into a Buddha field.

There will be skeptics—Tibetans as well as Westerners—who will believe that these events have arisen out of ignorance and vanity. They will contend that the realities of power politics are the flesh and bones of all such situations and that mystical explanations are merely the stuff fed to believers to support their faith. The priestcraft of Tibetan lamas, they will say, is no less pernicious because of its inimical efficiency. The stakes are indeed enormous—control over millions of dollars of assets, power over millions of minds and hearts, and the spiritual authority generated by intense and unremitting adulation and devotion. It is indeed regrettable that such mundane and materialistic vision has been lent support by the political wrangling at Rumtek. But surely the faith that sustains the genius of the Karma Kagyu pantheon will survive it.