“This is vulgar,” A. pronounced loudly into my ear. “This is vulgarity itself.” We were standing under an arch in the gymnasium of a public school in Manhattan in June 1971. Fifteen clean-cut, energetic young men were waving their arms about vigorously, leading the audience in a song called “Have a Gohonzon,“* set to the Jewish song “Havah Nagila”:

Have a Gohonzon,

Have a Gohonzon

Have a Gohonzon,

Chant for awhile.

You’ll find your life will be

Full of vitality,

Watching your benefits

Grow in a pile …

*Gohonzon: In Japanese, honzon indicates an object of worship. Go is an honorific prefix. Nichiren Daishonin embodied “Nam Myoho Renge Kyo,” as a mandala (Sanskrit for an object or altar on which buddhas and bodhisattvas are represented). The Gohonzon may be either a paper scroll or wood block with Chinese characters.

The audience, a black-and-white cross section of New York City’s diverse ethnic and economic population packed the room; they sang and clapped with ferocious enthusiasm.

“Look at them,” said A. “Look at their glazed eyes, will you? They’re fanatics.”

“The lecture was okay,” A. continued in a slightly more conciliatory tone. “That Japanese woman started to make some sense. But those testimonials—’I chanted for a new car and I got it!’ ‘I chanted for a boyfriend,’ ‘I chanted for money …’ And this stupid song! All of it’s crap! This isn’t what Buddhism’s about.”

The audience sang on:

Your surroundings may be loony,

Just remember:

Esho Funi!

“Now, that part’s true,” said A.

“This place is filled with very dangerous loonies. What’s Esho Funi?”

“It’s the doctrine of inseparability of person and environment,” I answered loudly, hoping he could hear above the noise. “Your environment reflects your inner life.”

“Well, not mine,” said A., putting on his coat. “This isn’t my reflection. I’m off.” And he stomped out.

I stayed on, frustrated that he had seen nothing beyond the egregious testimonials, beyond the silly song with its ungainly lyrics. I thought I had seen something, and, although I was also uncomfortable in those unfamiliar surroundings, I thought it worth exploring.

A friend from college had introduced me to Buddhism six months before. The tradition she practiced was Nichiren Shoshu, a Japanese sect of Mahayana Buddhism best known for its organization of laity, Soka Gakkai. She had joined Soka Gakkai (then called NSA, or Nichiren Shoshu of America) a year earlier. She had shown me her altar and prayer beads, and explained that if I chanted ”Nam Myoho Renge Kyo,” I could get anything I wanted.

“Anything?” I asked her, baffled. “Fame?”

“Um-hmm.”

“Sex?”

“Well,” she answered, “the founder of this Buddhism, Nichiren Daishonin, said that even one time chantingNam Myoho Renge Kyo might be enough.”

“Okay. Nam Myoho Renge Kyo! How about going to bed with me?”

“On the other hand,” she continued, “Nichiren Daishonin also said one million might not be enough. It all depends … ”

Nevertheless, I decided to try the practice. I knew a little about Buddhism from D. T. Suzuki’s essays. I had read Hesse’s Siddhartha and Herrigel’s Zen in the Art of Archery. I was twenty-two years old, a college graduate with a book of published poems but with no immediate plans. I needed focus. I tried yoga briefly, but could not manage the vegetarianism that I understood was mandatory. I looked at Zen, but the practice seemed stark and unfriendly. This Buddhism, strange on the outside, might offer a place to begin. Besides, my friend had acquired a pristine, buoyant spirit.

I began to chant on my own. My first contact with other Nichiren Shoshu Buddhists took place on a New Year’s Eve. We chanted Nam Myoho Renge Kyo together in their New York City Community Center on West 57th Street. At midnight we applauded and cheered and wished each other Happy New Year. I was elated. I could not fly or see through walls, but I had accomplished something of great difficulty, chanting for four hours without pause. I felt a quiet, reassuring rightness of purpose.

A. and I had known each other for several years. We taught together in the Poets-in-the-Schools program. We spent our summers in the Hamptons, part of the community of writers centered around East Hampton’s Guild Hall, the museum and cultural center. We lived nearby in the Springs, the famous artists-and-writers colony where Willem de Kooning lives and Jackson Pollack died. When I first told him about Nichiren Shoshu, A. was intrigued. He too had been interested in Buddhism. I lent him my set of borrowed books and pamphlets.

A. was disappointed in the literature. “The language is rough,” he told me. “And the philosophy is pretty thin.”

I became defensive. I suggested that the sect had been in this country only a short time. Its translation skills would certainly improve. Besides, the book was written for a mass audience who could not be counted on to understand subtleties without schooling. In any event, I had planned to go to an NSA discussion meeting in Manhattan. Would he come along? Reluctantly, he agreed.

After A. left the meeting I did not hear from him again for several months. When I met him by chance at a party in East Hampton, he asked if I was still practicing with NSA. He shook his head sadly. I would be sorry if I stayed with them any longer, he predicted. “No reasonable, intelligent person is going to fall for that garbage,” he warned. “Anyhow, they’re not your kind. You’re a poet. You’ve got something to offer. Why waste your time with inferior people?”

He himself had found real Buddhism, he told me. He was going to study with Trungpa Rinpoche. Had I heard of him? No, I told him, I hadn’t. “He’s a poet,” A. said. “He’s not shallow.”

A. stayed with Trungpa until Trungpa’s death in 1987, and then he proceeded to study with other Tibetan teachers. Despite my friend’s counsel, I’ve continued with the practice of Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism for more than twenty years.

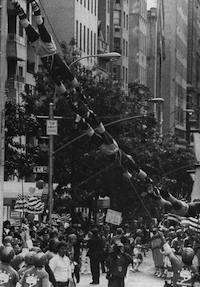

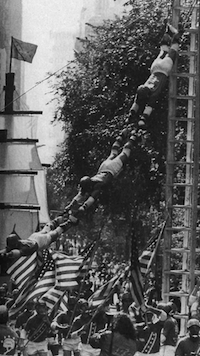

Others who knew about my involvement with the movement have been harsher than A. The most telling criticisms came from those who practiced other varieties of Buddhism. They wondered where, in Soka Gakkai’s visible and frenetic public display—its conventions and parades staged in major cities, its proselytizing groups gathered on street corners or swarming over college campuses—where was Buddhist dharma? Where was the contemplation, the dedication, the struggle for enlightenment, the evidence of responsibility to Buddhist practice that has characterized Buddhism for thousands of years? Where was anything of substance in what I was doing and advocating that others do?

People in the United States and Japan who join Soka Gakkai are not often the same kinds of people attracted to other forms of Buddhism. In the U.S., Soka Gakkai appeals to a spectrum of the population in diverse economic, racial, and cultural groups. Solid demographic and psychographic information is not available, but judging by articles in Soka Gakkai’s American weekly newspaper, The World Tribune, today’s American membership includes many people living in lower-income, inner-city areas such as Detroit and Watts, as well as middle-class people living in major cities and suburbs. (African-Americans make up an estimated twenty percent of the membership, a significantly larger proportion than can be found in other American Buddhist groups.) Few avant-garde artists, writers, or scholars of contemplative bent (those who seem drawn to other Buddhist groups) appear in news coverage. Meanwhile, the testimonials of famous Soka Gakkai members—including those of Patrick Swayze, Roseanne Arnold, Tina Turner, and Herbie Hancock and assorted sports figures—have made the practitioners known as Buddhists who chant for fame and fortune.

Most people assume that Nichiren Shoshu and Soka Gakkai are the same. They are not. Nichiren Shoshu is a religion, a sect of Buddhism. Soka Gakkai is a social, political, and cultural organization. Most Soka Gakkai members practice a version of Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism regularly. Yet, although the religion owes its eight to ten million worldwide members and (apparently) uncountable wealth to the lay organization, the complex historical alliance between these affiliations has never been harmonious.

Nichiren Daishonin (Nichiren means “Sun Lotus,” and Daishonin means “great sage”), the founder of the sect, was born in Japan in 1222. He began his career as a monk of the T’ien-t’ai sect of Mahayana Buddhism. The teachings of T’ien-t’ai are distinguished by their reverence for the Lotus Sutra (Saddharmapundarika-sutra in Sanskrit). T’ien-t’ai places this teaching text a bove all others because of its emphasis on the universality of Buddha-nature and the promise that everyone—men and women alike—may attain enlightenment in this life, “as one is.”

At about the age of sixteen, Nichiren left his home province for Kamakura, Mount Hiei, and other centers of Buddhist learning. He spent several years studying the sutras and their commentaries as well as the teachings of different sects. In the end, he became convinced that Shakyamuni’s teachings in the Lotus Sutra pointed to the Great Pure Law that could lead people directly to enlightenment. At the same time, he surmised that he had been entrusted with the task of propagating the essence of the sutra in the Latter Day of the Law, the time identified by the Daishutsu (Sutra of the Great Assembly) as beginning about two thousand years after the historical Buddha. In 1279, Nichiren inscribed the Dai-Gohonzon, a mandala that he declared to be the ultimate purpose of his advent in this world.

Until his death in 1282, Nichiren Daishonin wrote voluminous dissertations on the Lotus Sutra and correct practice. He debated, proselytized, remonstrated with the government, and underwent a series of government-ordered persecutions, including an attempted beheading that was thwarted only by the auspicious appearance of a comet. His prophecies of natural disaster and foreign invasion that Japan would undergo came true. “No matter what you might think of his convictions,” I recall my Japanese history professor at Columbia telling our class, “his predictions were completely accurate.”

After Nichiren’s death, several sects of Nichiren Buddhism were founded by his disciples. By the second decade of this century, Nichiren Shoshu’s membership had declined, leaving it one of the smallest of the five surviving Nichiren sects. It took the tremendous propagation efforts of Soka Gakkai to popularize it.

The original name for Soka Kyoiku-gakkai means “Value-Creation Education Society.” The organization was founded in 1930 by a teacher and educational theorist named Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, whose circle was educational, not religious, in nature, and the membership consisted mostly of schoolteachers.

Makiguchi became friends with a Nichiren Shoshu lay member and school principal. The evangelical Buddhist set out to convert Makiguchi, basing his appeal on those philosophical similarities which both men perceived in Nichiren Shoshu and in Value Creation Theory. According to community lore, their discussions ended in a somewhat formal debate, which Makiguchi lost. As a consequence, he converted to Nichiren Shoshu, along with Makiguchi’s followers, including his principle disciple, Josei Toda.

In 1943, at a time when Soka Kyoiku-gakkai had a membership of about three thousand, the Japanese military ordered all religions to align themselves with Shinto, the native Japanese religion. Makiguchi, together with a group of Nichiren Shoshu priests, challenged the decree. He was arrested and imprisoned, as was Toda. Makiguchi died in prison in 1944 at the age of seventy-three. His disciple, Toda, then forty-four, was released a year later.

The impact of his master’s death, and of his own mystical vision of Buddhism while in prison, led Toda to assume leadership with a mission to expand the organization’s membership. By the end of the war, the membership of Soka Gakkai had all but disappeared. Five years later, under Toda’s stewardship, the membership had regained fifteen hundred families. At a meeting held at a Nichiren Shoshu temple, Toda made the following pledge to his pupils: “I intend to convert 750,000 families before I die. If this is not achieved by the time of my death, do not hold a funeral service for me but throw my ashes into the sea off Shinagawa.” He met his goal by 1957 and died the following year.

Soka Gakkai today claims between eight and ten million members, living in more than one hundred countries. It sponsors an influential Japanese political party, Komeito, several high schools and a university, two art museums, several publishing companies, various newspapers, and many Japanese national and international cultural associations. It has acquired massive amounts of money and property.

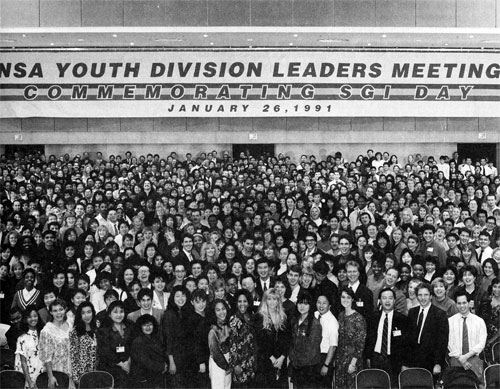

Soka Gakkai’s American branch was founded in 1960 by a Japanese law student named Masayasu Sadanaga (now known as George M. Williams), who had been a Soka Gakkai member in Japan. In the eighties, at its high point, the American organization boasted a total of 500,000 members, a number that—if anywhere near accurate—would make the Soka Gakkai the largest Buddhist organization in the United States.

But in Japan, Soka Gakkai’s success has come with a price. Extravagant financial growth over the past fifty years has been accompanied by a reputation for corruption. This spring, the New York Times reported that several years ago the organization was fined millions of dollars for interest payments on undeclared income. In 1990, the police discovered a Soka Gakkai vault containing $1.2 million in yen notes hidden in a garbage dump in Yokohama. More recently, according to the article, $11 million connected with the proposed purchase by Soka Gakkai of two Renoir paintings disappeared. This, in turn, raised questions about whether the lay group was stashing money away for political payoffs. In November 1991, the head temple of Nichiren Shoshu excommunicated the membership of Soka Gakkai en masse. This action is now forcing members throughout the world to choose between joining a Nichiren Shoshu temple or remaining with an unchurched and religiously compromised Soka Gakkai.

Nevertheless, the organization prospers. Soka Gakkai of America now (more realistically) puts its active membership at about 140,000—significantly lower than earlier estimates but still an impressive figure. Its members hold monthly meetings that seek to initiate new members as well as provide information and fellowship to established practitioners. Although members no longer sing “Have a Gohonzon” during meetings, and street-corner proselytizing has been discouraged, the organization continues to emphasize acquisition of material and spiritual benefits as a path to salvation.

Is Soka Gakkai/Nichiren Shoshu the true American Buddhism? To an observer, the practices of Soka Gakkai seem tailor-made for the American fast-food, instant-wish-fulfillment culture. You can chant for money, for a better job, for love, for any of the 108 human desires symbolized by the 108 prayer beads that Nichiren Shoshu members hold while they chant. An observer would note that Soka Gakkai practitioners spend far more time in discussion meetings and other group activities than they do in disciplined contemplation or consultation with Buddhist teachers. Because its emphasis falls on action rather than view, Soka Gakkai appeals to a broad range of Americans with varying educational backgrounds, even as it may alienate those who enjoy meditative Buddhist traditions. Without looking further, an observer might reasonably conclude that Soka Gakkai represents only a simplified version—or even a cynical perversion—of Buddhism created for American consumption. But if Soka Gakkai appeals to the American Dream, it has appealed to the Japanese Dream as well.

In the early fifties, during Soka Gakkai’s reconstruction, the then president, Josei Toda, succeeded in attracting a vast number of potential converts by describing the mechanism of Buddhist practice as a money-making machine:

Suppose a machine which never fails to make everyone happy were built by the power of science or by medicine …. Such a machine, I think, could be sold at a very high price. Don’t you agree? If you used it wisely, you could be sure to become happy and build up a terrific company. You could make a lot of money. You could sell such machines for about 100,000 Yen apiece.

But Western science has not yet produced such a machine. It cannot be made. Still, such a machine has been in existence in this country, Japan, since seven hundred years ago. This is the Dai-Gohonzon. [Nichiren] Daishonin made this machine for us and gave it to us common people. He told us: “Use [the machine] freely. It won’t cost you any money … And yet, people of today don’t want to use it because they don’t understand the explanation that the Dai-Gohonzon is such a splendid machine.

Toda’s words caught the attention of those Japanese impoverished by the Second World War and desperate for survival. In like manner, the appeal attracts many Americans living in the inner cities who are desperate for a way to improve their lives. For these people who know little material prosperity, the more conventional Buddhist view—that enlightenment is encouraged by abandoning all attachment to material things—is virtually senseless. After all, you must first have an adequate supply of food or own a car or a washing machine before you can give up an attachment to them.

The white middle-class practitioners who follow Zen, Tibetan, or Theravadan Buddhism are wary if not downright disdainful of Nichiren Shoshu but—whether they acknowledge it or not—they are involved in a dilemma with striking parallels. The issue for them is not money but ego. In a culture where low self-esteem and depression are endemic, the question arises: “Does one have to have a healthily developed ego to give it up?” Yet many of the same middle-class, materialistically secure white practitioners of other traditions have remained hostile to Nichiren Shoshu without investigating its different economic and cultural contexts.

To traditional Buddhists the idea of a Buddhism that encourages its practitioners to chant for BMWs appears blatantly heretical, and the description of the group’s object of worship as a machine for granting wishes sounds ridiculous. Even so, the practice of Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism is not trivial, nor is its effect upon members’ lives shallow. Gongyo, the daily practice of the Nichiren Shoshu membership, consists of morning and evening recitations of the Lotus Sutra as well as chanting Nam Myoho Renge Kyo repeatedly.Gongyo,** which literally means “assiduous practice,” is performed while practitioners sit before theGohonzon, a replica of Nichiren’s original mandala. During gongyo, two chapters of the Lotus Sutra are recited from Chinese characters (using Japanese pronunciation) and are repeated five times in the morning and three times at night. After each reading, practitioners silently recite prayers that offer thanks for protection by the Buddhist gods, praise the virtues of the Dai-Gohonzon, acknowledge the succession of the chief priests, present a petition for world peace and attainment of enlightenment, and pray for the well-being of ancestors—all of which have parallels in the daily services of Buddhist parishes in many different Asian cultures, as well as in Japan’s Soto Zen tradition. After the final reading, members chant Nam Myoho Renge Kyo, usually for five or ten minutes, but occasionally for several hours. The liturgy of gongyoencourages one to clear the mind of wishes, anxieties, and other distracting thoughts so that when it is time to chant Nam Myoho Renge Kyo (the most important part of the practice) the mind will be sufficiently stilled to concentrate on the Gohonzon. The goal of this “assiduous practice” is the fusion of one’s mind with the reality of the Gohonzon—it means reading the Chinese characters not simply with one’s eyes but “with one’s life”—through chanting Nam Myoho Renge Kyo.

**Gongyo: In general, gongyo means the recitation of Buddhist sutras in fornt of an object of worship. In Nichiren Shoshu and Soka Gakkai, gongyo means to recite part of the second chapter and the whole of the sixteenth chapter of the Lotus Sutra in front of the gohonzon, followed by chanting.

The literal translation of the chant is “Devotion to the Lotus Blossom of the Fine Dharma.” But Nichiren Shoshu provides specific interpretations: Nam—“devotion of both mind and body”—to Myoho, a word indicating that all life and death phenomena are united in a “mystic” or mysterious manner. Myoho indicates “the Mystic Law” of Renge, the lotus that reveals its seeds (its cause) as it blossoms (its effect) simultaneously—therefore, “simultaneous cause and effect.” This is invoked in our lives through Kyo, the word for dharma, sutra, or the sound of its teachings.

What Nichiren Shoshu members unite with when they chant to the Gohonzon is a depiction, in Chinese characters, of the “Ceremony in the Air,” described in the Lotus Sutra as an assembly of Shakyamuni’s disciples floating in space above the saha (impure) world. When the Bodhisattvas of the Earth appear, Shakyamuni reveals his original enlightenment in the remote past. He then transfers the essence of the sutra specifically to the Bodhisattvas of the Earth led by Bodhisattva Jogyo (Vishishtacharitra in Sanskrit), entrusting them with its propagation two thousand years in the future (our own time). Chanting to theGohonzon then both invites and affirms attendance at this assembly of bodhisattvas.

The philosophical lineage of Nichiren Shoshu purports that although the material and the spiritual are two separate classes of phenomena, they are in essence inseparable, a “oneness of body and mind.”

T’ien-t’ai sought to clarify the mutually inclusive relationship of the ultimate truth and the phenomenal world asserting with this principle that all phenomena—body and mind, self and environment, sentient and insentient, cause and effect—are integrated in a life-moment of a common mortal. Pre-Lotus Sutra teachings generally hold that all phenomena arise from the mind, but in T’ien-t’ai teachings the mind and all phenomena are “two but not two.” That is, neither can be independent of the other.

In pre-Lotus Sutra teachings, earthly desires and illusions are cited as causes of spiritual and physical suffering that impede the quest for enlightenment, obscuring Buddha nature and hindering Buddhist practice. According to T’ien-t’ai’s intepretation of the Lotus Sutra, however, earthly desires and enlightenment are not fundamentally different: enlightenment is not the eradication of desire, but a state of mind that can be experienced by transforming innate desires.

Beginning Nichiren Shoshu members establish their practice by chanting for whatever they want. I had friends who started off chanting for cheaper drugs and free money. Like them, I treated the Gohonzon as a pimp. I wanted to see if chanting would work. I set about praying for things (a summer job, a girlfriend, even a good parking spot) that would fill immediate needs or give instant pleasure. Some things I got; others I didn’t. The things I really needed—such as better relationships with people and with myself—eluded me. Nevertheless, I continued to chant. Gradually, my interest in short-term material benefits was displaced by a hunger for longer-term spiritual ones. I found that chanting incessantly about difficult personal problems, like polishing a mirror, brought clarity to my situation. The more difficult or painful the motivation for my chanting, the clearer the mirror of my faith reflected my ownership of whatever troubled me. I could no longer deny the responsibility for my predicaments. In my experience, the activity of chanting for material or spiritual things becomes a process of cleansing one’s spirit, not corrupting it; and Buddhists who began by chanting for hotter cars ended up driven to awaken themselves and help others, at times with great energy and joy.

“Will you please tell me what playing the trombone has to do with Buddhism?” my friend A. demanded. It was during my first year as a Buddhist. I had told A. that I’d planned to join Soka Gakkai’s brass band. “You want to be in a marching band? Didn’t you do enough parading in military school?”

Indeed I had. I was sent to military school when I was twelve and remained there until I was eighteen. I promised myself I would never march again. Yet, here I was in the Soka Gakkai Brass Band.

I had no satisfactory explanation of the relationship between marching in a brass band, attending Soka Gakkai conventions, donating money to the organization, and Buddhism. I had only Soka Gakkai’s official answer: these movement activities would yield personal benefits and further the cause of world peace. In any event, they certainly benefited Soka Gakkai.

In the ten years during which I practiced as a Soka Gakkai member, I attended their conventions all over the U.S. and Japan. These were always spectacular public exhibitions, such as the show performed on a massive floating island stage built off the Waikiki shore. I got to see little of them, however. As a Young Men’s Division member, I was often put in charge of luggage and remained at the hotel, or was appointed caretaker of one or another member who had suddenly become unhinged, such as the young man who insisted on walking—naked—backward up and down the hotel corridors and dressing only to take a shower.

I cannot say that I entirely relished membership in Soka Gakkai. I confess that playing in the Brass Band was always an embarrassing chore. Discipline was strict and not always administered by wise leaders. Yet, the core of my Buddhist practice remained chanting.

In 1980, American Soka Gakkai members were not aware that the Nichiren Shoshu clergy and the Soka Gakkai administration had become entangled in a dispute. The clergy alleged that Soka Gakkai was secretly planning to establish itself as an independent sect of Nichiren Buddhism. The scandals and controversies that resulted were documented in the Japanese press but not in the American press. Possibly as part of Soka Gakkai’s plot to secede, American members were given new versions of the prayers of gongyo that included homage to Soka Gakkai founders. George M. Williams announced that a new Head Temple might be constructed on a tract of land purchased in the Rocky mountains. Otherwise, Soka Gakkai of America asserted that nothing out of the ordinary was happening.

My friends and I eventually learned about these things from a young Japanese who had been appointed chief priest of the Nichiren Shoshu temple in New York. He was amazed that Soka Gakkai in this country continued to deny the problems in Japan, especially because he believed that knowing about them was essential to an American member’s understanding of the practice.

With the information provided by the young priest, and from copies of an English-language Japanese newspaper, I began to discuss this situation with the thirty or so active members in the group I headed, and with my senior leaders. Rather than answering my questions, my seniors admonished me, declaring that I was slandering Buddhism.

When efforts to force the American Soka Gakkai to openly discuss the implications of the political situation failed, the young priest decided to publish the details on his own. Eventually, he printed a heavily documented pamphlet and mailed it to as many members as he could locate. Soka Gakkai successfully pressured Nichiren Shoshu to fire him.

My friends and I were similarly dismissed. Our dismissal was carried out in a particularly Japanese manner. Instead of being thrown out publicly, our group was simply not included in the next reorganization of groups that define the Soka Gakkai membership. We became, so to speak, nonpersons.

During these last twelve years of solitary practice, I have had to answer questions I might not otherwise have had to confront had I remained in Soka Gakkai. How deep have the dynamics of mass-movement culture affected my understanding of Buddhist experience? How much of my knowledge of this religion, for example, is knowledge of Buddhism, and how much is Japanese cultural bias? There are no easy answers, although my ignorance makes me a comrade in arms with the many other American students of Zen, Tibetan, and Theravadan Buddhism who wrestle with these same questions.

But in front of the Gohonzon those questions don’t feel very important; nor do my friends’ descriptions of vulgarity or materialism. I am left where I began: by myself, at my altar, conscious of a larger truth—that the Great Assembly of bodhisattvas described in the Lotus Sutra is a reality taking place now, at every moment of our lives.