Christmas Humphreys, a noted early English Buddhist scholar and proponent of Zen, once declared Shin “a form of Buddhism which on the face of it discards three-quarters of Buddhism. Compared with the teaching of the Pali Canon it is but Buddhism and water.” In fact, Shin Buddhism is often portrayed this way by those who believe meditation practice constitutes the core teaching of Buddhism. However, comparisons with meditation actually miss the point of Shin Buddhism, which offers instead a discipline of the heart demanding deep self-reflection, constant awareness of one’s gratitude to the Buddha, and compassion for all beings.

The basic teaching of Shin Buddhism, founded by the Japanese priest Shinran (1173-1268), revolves around the belief that Amida Buddha, the Buddha of Eternal Life, has vowed to create an ideal spiritual world—”The Western Pure Land”—in which all beings, regardless of social, intellectual, or moral capacities, can attain final liberation and enlightenment. For the ordinary person, the key to rebirth in the Pure Land is the recitation with faith and gratitude ofnamu amida butsu, the name of Amida Buddha. Essentially a teaching of salvation through faith alone, Shin Buddhsim requires no special practices or meritorious good deeds to gain entry to that land.

It is true that Shin rejects monastic disciplines such as meditation and precepts, which have traditionally been the core of Buddhist practice as the way to enlightenment. It views those practices as merely the means to insight into ego and its attachments. By going further into the understanding of egoism itself, Shinran altered the general Buddhist assumption that enlightenment could be achieved through determined, rigorous practice. No matter how demanding or difficult such practices might be, in Shinran’s view they were only an attempt to build a bridge to the infinite through finite acts. If salvation were possible, he professed, it was only by virtue of the Buddha’s action, not by those of the practioner’s own unstable mind.

I first encountered Shin Buddhism as a soldier during occupation duty in Japan at the end of World War II. Being a Christian fundamentalist at the time, I was shocked to discover that there was a teaching of grace in another religion. My studies and activities in the Shin community since then have given me the opportunity to observe at close range many aspects of temple life, as well as the issues and problems now confronting the tradition as it struggles to survive in, and contribute to, the highly competitive contemporary American religious environment.

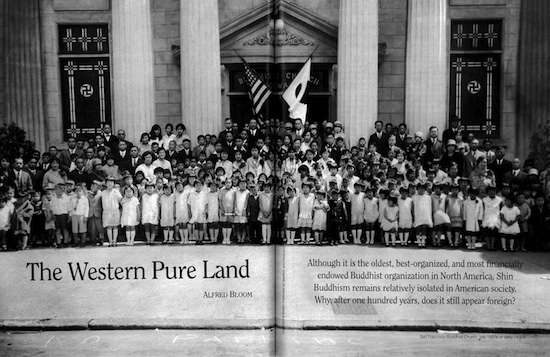

Over its almost one-hundred-year history, the Buddhist Churches of America (by far the largest American Buddhist movement) has become a nationwide organization. However, at present it is faced with a host of problems: decreasing memberships, shrinking ministry, ambivalence about opening to the wider community and problems in translating or interpreting the teaching in a way that is meaningful to modern, well-educated, thoughtful members, as well as to interested inquirers from outside.

Shin Buddhism first came to America with the immigration of Japanese workers toward the end of the last century. The first-generation immigrants were not permitted to become citizens, and in California, Oregon, and Washington, laws were designed to prevent the acquisition of land by Japanese. Such legislation made it difficult even to secure land for temples. Eventually, however, such land was acquired through their children, who were automatically citizens by virtue of their birth in America.

Because of their tenuous position in American society, the Japanese elders nurtured Japanese values and culture in their children through temple activities and language schools. However, the dominant society regarded the lack of assimilation as un-American (notwithstanding the fact that anti-Japanese prejudice had effectively blocked or rejected Japanese efforts to assimilate.) Hostility toward Buddhism was particularly strong in Hawaii, where there was considerable pressure to convert to Christianity. One writer claimed that “no alien could be transformed into a “wholehearted American citizen” unless he accepted “the Christian ideals of personal responsibility, of duty to God and to fellow men.”

Considering the cultural milieu of early Shin Buddhism in America, we must call attention to the farsighted efforts of Bishop Yemyo Imamura, who led the Shin Buddhist community in Hawaii from 1900 to 1932. Undaunted by anti-Japanese sentiments, he held to the ideal of uniting Japanese and Western culture and Americanizing the Japanese, meaning that they would be loyal citizens in their adopted country. Boy Scout troops were organized, and he worked to Americanize Buddhism through the development of hymns, sermons in English, and Sunday school programs. Even the physical arrangment of the temples, including the use of pews and pulpits, reflected the desire to be American. Bishop Imamura articulated his ideal clearly:

The true religion out to rise above and be applicable to any country and nationality and so assimilate with every state and nation. The final object of Hongwanji [Imamura’s Shin Buddhist organization] is to plant the gosepl of Buddha Amita in the true spirit of every nation in the corners of the world…

This ideal is still held by many, but social and political conditions after Bishop Imamura’s tenure rendered the goal only a distant hope.

On the mainland, the initial missionaries also had the idea of spreading Buddhism among non-Japanese. Nevertheless, their main efforts were always directed at the religious and social needs of Japanese immigrants. By 1933 it was recognized that the future lay with English-speaking ministers. However, the educational systems for prospective ministers required them to study in Japan and to be fully fluent in Japanese. The educational program might have become more practical in time had it not been for the onset of World War II.

With the advent of hostilities, the majority of persons of Japanese ancestry living on the West oast (including those who were United States citizens) were removed from their homes by the U.S. government and interned in caps euphemistically called “relocation centers.” While many second-generation Japanese-Americans volunteered and fought valiantly in World War II, their families lived under guard in the camps.

As a consequence of these difficult condictions, all forward momentum the training of Shin ministers and in the expansion of the movement was placed on hold. In the postwar period the Japanese had to reestablish their lives after suffering great personal and financial losses. They were permitted to return to their homes in 1945, and by the mid-fifties, most of the temples were well on the road to recovery from the setbacks of the war years. In addition, because of the relocation of significant numbers of Japanese-Americans to areas east of the Mississippi during the war years, new Shin Buddhist congregations had been formed in numerous eastern cities.

In order to deal with the increasing need for English-speaking ministers, the Institute of Buddhist Studies in Berkeley was gradually developed as a seminary and graduate school. Through its recent affiliation with Graduate Theological Union, the Institute now functions within a Jewish and Christian community as the only non-Western religious school of higher learning with an ongoing academic and religious environment. Stimulated by Buddhist-Christian dialogue, the work begun by the early missionaries to integrate Shin Buddhism within mainline American religion has continued to make great strides. Despite the progress made in the area of ministerial education, however, the life of the temples remains what it has been for decades.

In his book American Buddhism, Charles Prebish notes that “the national organization [Buddhist Churches of America] finds itself in the curious predicament of having been present on American soil longer than any other Buddhist group and having acculturated the least.” He might also have noted that Shin Buddhism not only has the longest history in America but is the best organized and most endowed with human and financial resources. Yet it has not been able to make the transition into another culture. For this reason, the Shin Buddhist movement in the United States is undergoing an attrition of crisis proportion.

According to one study, the number of Shin Buddhist ministers in the United States peaked in 1930 with 123 ministers. By 1981 there were seventy-one. Currently, out of a total of sixty temples in the United States, ten do not have full-time ministers, while eight ministers serve two or three temples each. Sometimes even retired ministers are pressed into service. In 1977, general membership in the Buddhist Churches of America stood at 21,600 families (approximately 65,000 people), but figures from 1994 show that the number has fallen to 17,755.

“Outmarriage” (i.e., marriages with individuals of other ethnic backgrounds) among Japanese-American youth has grown to about 50 percent, and few of the children of mixed marriages or their parents are active in the temples. If there is any sign of hope for Shin Buddhism to survive in the United States, it lies in the “dharma schools” for small children, which are still thriving in Shin temples. Though the numbers rise and fall, in 1984, dharma-school enrollment totaled approximately 2,550 students while by 1993 the number had grown to 3,045.

As in Japan, for the rank-and-file members of Shin Buddhist temples, the tradition has come to emphasize memorial services for the dead. Along with other forms of Japanese Buddhism with a similar emphasis, Shin is generally dubbed a kind of “Funeral Buddhism.” This perception of Shin has persisted in its transfer to the West and has also contributed to the decline of members and ministers. Japanese American youths are not greatly inspired to become ministers in such a tradition when there are so many other options.

In the early years of Shin in America, ministers were enlisted in Japan and sent to the West. Because of the large numbers of first-generation Japanese in the community, this arrangement was optimal. Now, however, Japanese priests who come to America have great difficulty relating to the younger generations. In addition, life for a priest is better in Japan. There, priests are more or less in control of their temples, whereas in America they are considered to be employees of the congregation. Therefore, most Japanese priests who come to the U.S. do so only on a temporary basis while they wait for permanent in positions in family temples back home.

While external, historical, and sociological circumstances are partially responsible for attrition in Shin, a lack of dynamic leadership is also to blame. Despite the high perentage of people with professional careers among its members, Shin lacks a vibrant intellectual center. Few members have the training and background in religious and philosophical studies to explore issues critically and to move the community in a more dynamic direction. Over the years, several attempts have been made to upgrade and improve education resources, but dharma-school teachers are all volunteers, and there are few programs that offer systematic training for teachers. Although these programs do introduce young students to basic Buddhist teachings, exposure to the principles of Shin Buddhism itself is very limited. Young people frequently leave the temple at adolescence or when they go to college and may not return—if they return at all—until middle age, when they have their own families. Adult classes are few, and, although the amount of literature available in English has increased, few members read such materials. Consequently, laypeople who should be taking the lead in sharing the teaching with others have only a hazy understanding of the relationship of early Buddhism to Shin or of the content of Shin Buddhism itself.

Although a school has been established to train English-speaking ministers, trainees, must still go to Japan for a number of years to imbibe the traditional teaching and learn Japanese. Since the teaching given in Japan is shaped by issues of Japanese history and culture, the ministers who return have difficulty culturally translating the teaching. In my own limited experience of listening to sermons, I have rarely heard any discussion of Buddhism and contemporary issues, and although doctrinal themes may be addressed, the further philosophical implications and meanings are seldom explored. In fairness, however, I must indicate that members often desire simple presentations.

For all these reasons, Shin Buddhism still remains relatively isolated in American soceity, where even after one hundred years it appears to be a foreign religion.

Clearly, the future is up to the membership of the temples. Dr. James I. Doi of the Seattle Buddhist Temple, formerly a Dean of the School of Education at the University of Washington, has suggested several strategies that temples might empoloy to attract new members. Among these are programs that would place education above the social aspects of temple life. Members should be encouraged to make use of the increasing variety of literature on Buddhism, and temples should cultivate members who can speak articulately about Buddhism in English.

According to Doi, if these ideas are put into practice, despite the fading of Japanese-America culture, Shin Buddism will be able to contribute to the flowering of American Buddhism in that way will enter ” the mainstrema of American intellectual and spiritual life.” With the help of perecptive leadership in the lay community and from the clerics, Shin’s great potential in the United States may yet be realized.