I’VE HAD TRULY MIXED FEELINGS about writing this little meditation, but then it is not costumed as a dispensation. We apparently drown in discursive texts, lists of principles and, on occasion, turn in despair from recondite Buddhist studies to the poetry of Han Shan and Gary Snyder and many in between. I think it was a Zuni who said, “There are no truths, only stories.” Perhaps that is why we are drawn back to The Blue Cliff Record and The Book of Serenity. After all, we live within a story and our own story is true. This is only to say what I have to offer is a tad simple-minded compared to what has been offered to me.

Why sit? I tend to sit every morning in the Soto tradition because I was taught to do so back in the seventies by Kobun Chino Sensei and he appeared on an immediate basis to be the master of a superior secret. I have a zafu in the granary study of my farm in northern Michigan, also one in the loft of my log cabin in a rather remote area of the Upper Peninsula. There is a river right outside the door of the cabin, and other than being a truly fine river it is also a reminder of a Tung-shun quote Jack Turner, a student of Robert Aitken, sent to me:

Earnestly avoid seeking without,

lest it recede far from you.

Today I am walking alone,

yet everywhere I meet him.

He is now no other than myself,

but I am not now him.

It must be understood in this way

in order to merge with suchness.

I also sit on logs out in the forest, big rocks in gullies, stumps, three pillows in hotels, car seats, hard plastic seats in air terminals, soft cushioned seats in offices, while standing still for a long time—I would sit on my head if it were possible. I once saw a Chinese acrobat do this and was quite envious. I’ve always lived quite far away from a teacher so it is possible you will not think this is formal Zen practice. But then I am willing to call my practice “bobo” after a comic religion I’ve been inventing lately, or if you wish, just plain dogshit, an indication that a dog has passed this way. As a matter of fact, when outside I often sit with my dog. When you have reached the ripeness, or deliquescence, of fifty-five years, you are less concerned about what things are called. It is the liberation to be found in mouthy old geezers everywhere, and is uncomfortably close to the liberation in the energy of youth.

I have sat in all these places for twenty years because I didn’t want the act to become another version of the Lord’s Prayer or a private church service—in other words, to keep the ritual fresh. As a young man I was a Christian zealot and managed to suffocate my faith in theology and textual squabbles. Too bad the great Buddhist poet and scholar Stephen Mitchell hadn’t published his Gospel According to Jesus before he was born so I could have eaten the wheat rather than just breathing the chaff.

Frankly, when I first started sitting so many years ago it was for the selfish reason of stopping my head from flying off. It did so nearly every day, and I was becoming more than a little frightened. To crib from Aristophanes, whirl was king, a not unusual state for a young poet to find himself in. (I say “himself” because it’s me. I cannot humanly countenance forms of Zen that involve gender considerations.) A poet’s livelihood is in his moods and if there is not a larger, selfless backwall to these moods he tends to end up in madness and death. A number of family deaths had told me that life was a great big house fire of impermanence. What’s more, that all my habituation and conditioning, my gluttony, alcoholism, drug ingestion, neuroses weren’t helping one bit. And it is easy for a young poet to be obsessed with Yeats’ notion that life is a long preparation for something that never occurs. Sitting immediately told me that life was a preparation for itself, something I had already suspected from my lifelong immersion in the natural world. Perhaps poetry helped create the freedom that must be there before there is freedom.

So much for piths and gists, the junkyard of apothegms, the plodding oinks of wisdom. Sitting on a stump I feel a little closer to the idea that I’m a member of just one of possibly thirty million species. Some people don’t like to count bugs because they are frequently obnoxious. A stump or log seems to help me assume. Zen as a glyph for the vehicle of reality, the water that just happens to be contained by a glass and a myriad of other containers. Mistakes are made when students are led to believe that the water pipes, the steel culverts, the plumbing are the river.

Stumps and logs help me forget the world of achievement, disappointment, rewards, the illusion of being right, struggling to hold the world together, and help me shed many of the illusions that the very notion of “personality” is heir to; there is a frequent mistake here in equating personality with “ego,” which is a Freudian term and unfortunately rather Prussian. The point seems to be to rid yourself of vanities in order to understand your true character. In sitting, the host returns to the original mind while the guest dithers. Then the dithering stops.

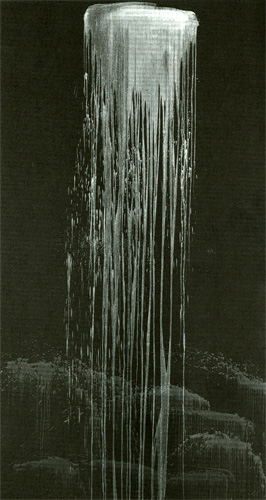

For years I’ve had a quote by Deshimaru pinned above my desk: “You must concentrate upon and consecrate yourself wholly to each day, as though a fire were raging in your hair.” What a ruthless statement. But maybe not. Both you and a piece of wood burn up, and at the end of the day you have ashes which don’t return to wood. This is wonderfully obvious but can be forgotten for years at a time. Sometimes the statement wears out and I put it away for a while to rest, though it doesn’t take long for it to refresh itself. I use similar statements by Foyan, Dahui, and many others to zap myself. They are excellent cattle prods to the wayward ox who might be spending too much time in front of the butcher shop window wondering at the way it all ends.

THERE IS A PARTICULAR PROBLEM for the artist, writer, poet who begins early to separate himself for vision and lucidity, also to get the work done, and then this separation can easily become distorted, a “fiction” in itself, a personality egg you drown within juices of your own making. Thus, the artist’s Zen can become the arhat’s Zen, harsh, dry, attenuated, remote, somewhat selfish. Frequently he would be better off at an American Legion barn dance or sitting in a country bar talking to farmers.

I have to travel a great deal to earn my livelihood, and there is nothing quite like travel to make you a victim of moods. It would be nice to carry a shoe box to store these moods in-then you could abandon them in a locker at La Guardia. The reason why moods are so hard to locate and identify is they don’t exist, though popular culture teaches us to indulge them. National culture seems mostly interested in teaching values that get us to work on time. When you sit, all of this cultural habituation and conditioning drifts away.

I’m reminded daily that I’m no great shakes as a thinker and doer in the philosophical arena. I was taught in college that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny but I still have to keep looking up the meaning. I know four or five teachers, and where would they be without plain old sitters? Often my life seems too monstrously active and I’m learning that there is no need to be in a hurry if you can only do one thing at a time. Professionally, I’ve shown no expertise outside the arena of imagination. One of my “amusements” is to try to find and follow black bears, which have always been a dharma gate for me, aside from being bears. Black bears aren’t remotely as dangerous as grizzlies, but it is best to be in a state of total attention, because, frankly, the bear is. We want to fully inhabit the earth while we are here and not lose our lives to endless rehearsals and illusions. Perhaps my sitting is more like that of an addled bird, but the bear is always out there, not calling to me, just a bear.