Biography and autobiography in Tibet are important sources for both education and inspiration. The authors involved in the Treasury of Lives mine primary sources to provide English-language biographies of every known religious teacher from Tibet and the Himalaya, all of which are organized on their website.

Without mindfulness you are like a heartless zombie, a walking corpse.

—Khenpo Nyoshyul Rinpoche (1932–1999)

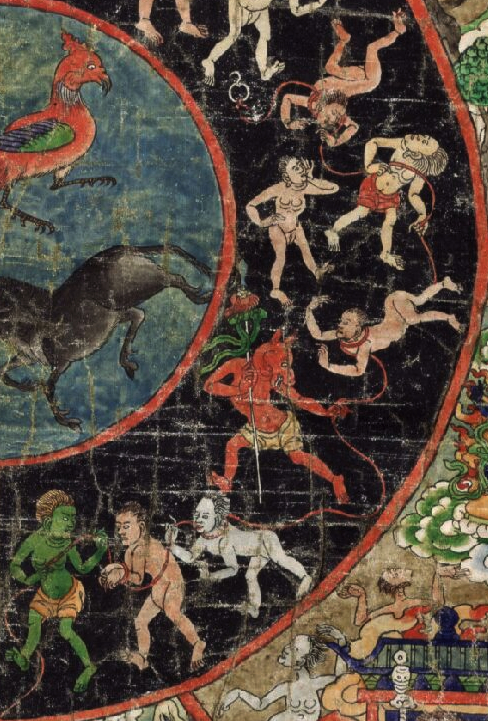

Contrary to the popular modern view of Buddhism as a gentle philosophy of teachings that peacefully lead one down a path of self-reflection, Buddhist literature has never shied away from the dark, frightening, and threatening—even prior to the popularization, around the 8th century, of outrageous and revolting tantric imagery. Take, for example, the preta, or “hungry ghost” realms, described by the historical Buddha. In this desire realm—one of six in which one can be born due to excessive greed—ghostly beings with mummified skin roam about with tiny necks and large, distended bellies, always hungry but never full.

The Buddha also described many layers of hell realms featuring a variety of horrendous punishments—all lovingly described in gory detail in traditional literature—such as being continuously cut by knifes and axes, or impaled on fiery spears. In Tibet, an entire genre of biographical-style literature sprung up around the stories of deloks—people that had presumably died, visited these lower realms, and returned to warn the living of the reality of the punishments awaiting them if they did not engage in proper behavior. Their pronouncements were sometimes recorded by their disciples and published in books. They also often show up as supporting characters in others’ biographies offering words of advice and wisdom. For example, in the biography of Taklungtangpa Tashi Pel (1142–1209), founder of the Taklung branch of the Kagyu school, a delok predicts that he will become liberated and attract numerous disciples.

Indian Buddhists and their Tibetan counterparts were no strangers to the macabre in the human realm, either. Some of the tales we have from the early dissemination of Buddhism in Tibetan, leading right up to the present day, are rife with magical activity that appears to reflect less-than-compassionate intentions. Take, for example, that of Ra Lotsawa Dorje Drakpa (1016–1128), a translator specializing in the Vajrabhairava cycle. He engaged in clan feuds over property and marriage rights, and claimed to have killed 13 other lamas, many of whom were propagating competing tantric cycles, using black magic. Among those he killed was Marpa‘s son, Darma Dode. Even Marpa’s most famed disciple, Milarepa, the great singing yogi-saint, began his career as a black magician bent on revenge: he killed dozens of villagers in a mantra-induced hailstorm before turning to Buddhism.

Indian Buddhists and their Tibetan counterparts were no strangers to the macabre in the human realm, either. Some of the tales we have from the early dissemination of Buddhism in Tibetan, leading right up to the present day, are rife with magical activity that appears to reflect less-than-compassionate intentions. Take, for example, that of Ra Lotsawa Dorje Drakpa (1016–1128), a translator specializing in the Vajrabhairava cycle. He engaged in clan feuds over property and marriage rights, and claimed to have killed 13 other lamas, many of whom were propagating competing tantric cycles, using black magic. Among those he killed was Marpa‘s son, Darma Dode. Even Marpa’s most famed disciple, Milarepa, the great singing yogi-saint, began his career as a black magician bent on revenge: he killed dozens of villagers in a mantra-induced hailstorm before turning to Buddhism.

Tsangnyon Heruka, the author of the popular versions of Marpa’s and Milarepa’s biographies, was known to wander around carrying a skull cup and wearing pieces of corpses he found, a fashion choice that can be traced back to the tantric practitioners of India that dwelled among the dead at various charnel grounds. Members of the Aghora sect of ascetics can still be found in India today, drinking out of skull cups and hanging out with the dead.

Zombies, spirits, and ghosts are prominent tropes in Buddhist history and Tibetan culture in particular, where they make repeated appearances in both oral and textual histories. In some cases, Indian tantras hark back to various spirits, demons, flesh-eating ghouls, smell-eaters, and ogres described in various scriptures. Add that to an extremely strong indigenous Tibetan tradition of belief in horrendous creatures such as flesh demons, hair demons, skin demons, demons that haunt mountain passes, and demons that steal children, and you have something truly frightful.

In some regions of Tibet, doorways are still constructed small and low so that zombies, with their stiff joints and limbs, can’t bend down low enough to pass through. Life stories of Buddhist masters abound with accounts of the subduing demons and ghosts through tantric means, occasionally in the most eccentric of ways. Gyelwai Lodro, one of the (possibly fabled) 25 students of Padmasambhava, was said to have the ability to turn zombies into gold, which he then buried as treasure for discovery by future generations.

Although abundant stories of ghosts, goblins, ghouls, vampires, and various other dark creatures of the night are taken quite literally by many, one should not dismiss them entirely as superstitious and naïve. Running alongside all of these beliefs was a nuanced understanding of the psychology of fear and perception born from a deep understanding of Buddhist philosophy. The female master Machik Labron (1055–1149) encouraged her students to face their fears directly by practicing alone on burial grounds and deserted bridges, places ghosts and demons were likely to haunt. She began the lineage of Chod, which teaches that instead of running from demons, we should welcome and feed them with our most precious possession: our bodies. In this way, attachment is cut, which is the meaning of chod. The system, first established in the early 11th century, presents another way of looking at all of the things that “go bump in the night.” In the words of Machik Labdron,

The origin of all demons is in mind itself.

When awareness holds on and embraces any outer object,

It is in the hold of a demon.

. . .

As long as there is an ego, there are demons.

When there is no more ego, there are no more demons either!

If there is no ego, there is no more object to cut through,

Nor is there any more fear or terror.

Free from all extremes, co-emergent wisdom

Give birth to the understanding of [the nature of] all phenomena.

This is referred to as the fruit of liberation from the four demons.