Biography and autobiography in Tibet are important sources for both education and inspiration. Tibetans have kept such meticulous records of their teachers that thousands of names are known and discussed in a wide range of biographical material. All these names, all these lives—it can be a little overwhelming. The authors involved in the Treasury of Lives are currently mining the primary sources to provide English-language biographies of every known religious teacher from Tibet and the Himalaya, all of which are organized for easy searching and browsing. Every Tuesday on the Tricycle blog, we will highlight and reflect on important, interesting, eccentric, surprising and beautiful stories found within this rich literary tradition.

Treasury of Lives: The Case of the Dalai Lama’s Cursed Boots

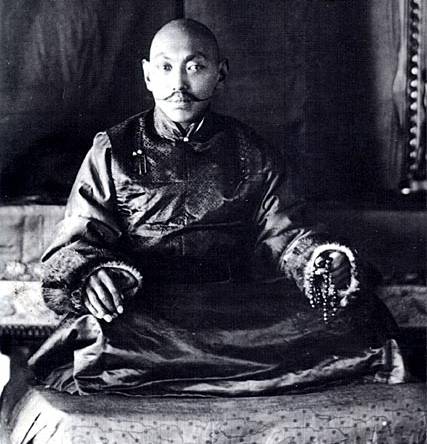

The 13th Dalai Lama Tubten Gyatso (1876–1933) is famous for his efforts to modernize Tibet and for alternately fleeing and facing down both British and Chinese powers. During his fascinating life—about which a great amount of detail is known—one of the most curious events is the assassination attempt he survived in 1900 involving a pair of boots and some black magic.

The 13th Dalai Lama was the first since the 8th, Jampel Gyatso (1758–1804), to live long enough to take control of the Tibetan government. For nearly a century a series of regents had ruled Tibet in place of the 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th Dalai Lamas. These regents amassed considerable power while in office, and had reason to prefer that the young Dalai Lamas not reach adulthood. During the 13th Dalai Lama’s youth, Tibet was ruled first by the 10th Tatsak, Ngawang Pelden Chokyi Gyeltsen (1850–1886), and then, after his death, by the 9th Demo, Ngawang Lobzang Trinle Rabgye (1855–1899).

The 13th Dalai Lama devoted himself to religious studies and refused to assume political power despite repeated request until the age of 20. Historically, Dalai Lamas were to take control of the government at the age of 18, but the 13th chose to wait until he had completed his religious studies.

Following his ordination in 1895, the Tibetan National Assembly and representatives from the major Geluk monasteries called on the Dalai Lama to fulfill his secular duties. Britain was then threatening the border with India, and Tibet was in need of a leader. The Nechung Oracle confirmed that the time had come, and the Dalai Lama was installed as the head of government on the eighth day of the eighth Tibetan month of that year.

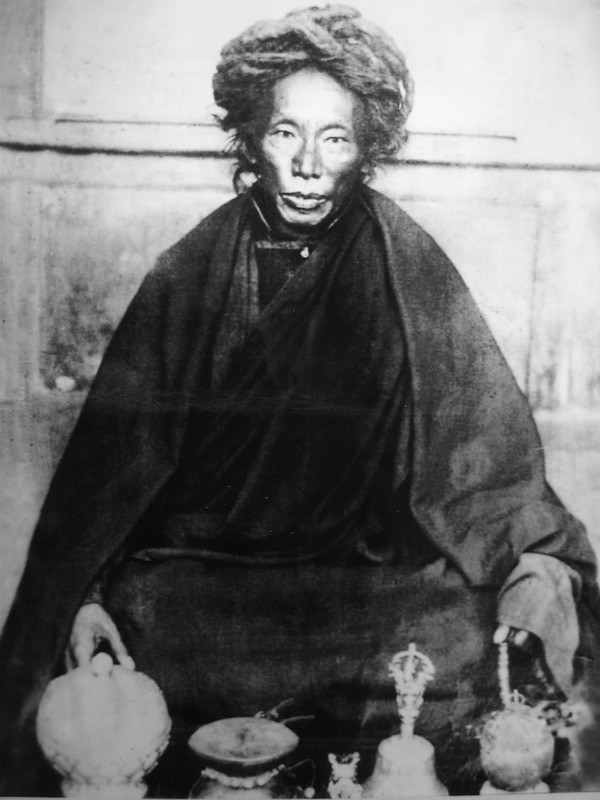

Before two years were out he had proven his acumen by negotiating an end to Qing Chinese hostilities in Nyarong, Kham, but in 1899 he began to have disturbing dreams, and consulted with the charismatic Nyingma lama Terton Sogyel Lerab Lingpa (1852–1926), who took the dreams as a sign that his life was in danger. The Dalai Lama’s tutor, the 3rd Purchok Jampa Gyatso (1824–1901), recommended he take the examination degree of Geshe Lharampa, the highest academic degree in the Geluk tradition. Following his advice, the 13th Dalai Lama became the first to hold the degree. The situation did not, however, improve.

According to Tibetan astrology, every 13th year of a person’s life is fraught with danger. The year 1900 was the Dalai Lama’s 26th year, and thus his second “obstructed” year. It was in that year that the Dalai Lama fell ill frequently, had little appetite, and grew physically weak.

In one account it is said that the Dalai Lama noticed that his health deteriorated whenever he wore boots presented to him by Terton Sogyel. When his attendants examined the boots carefully they found harmful mantra hidden in the sole. The government questioned Terton Sogyel, who declared his innocence and told them that when he wore the boots he too began to bleed from the nose. He told the officials the boots were a gift from another lama from Nyarong named Nyaktrul that was renowned for his magical powers.

In another account, the boots, prepared with mantra by Nyaktrul, had been giving to Terton Sogyel by the 9th Demo and were never worn by the Dalai Lama. In this version, it was the Nechung Oracle who called attention to the boots.

In either case, when Nyaktrul was interrogated he confessed that he had been recruited by the former regent, the 9th Demo, and his brother and manager Norbu Tsering. Nyaktrul had prepared an image of the meditational deity Yamantaka called Shinje Tsedak, depicting him with outstretched arms and legs surrounded with mantra, and with the name Tubten Gyatso and the word “mouse,” the birth year of the Dalai Lama, written inside the figure. He embedded this image in the boots as a means to sap the vitality of the Dalai Lama and cause his eventual death.

The government arrested the 9th Demo and members of his family. Under questioning Demo admitted his role in the plot. The Demo’s estates were confiscated and he was imprisoned in Lhasa. According to scholar of Tibet Melvyn Goldstein, the Demo was motivated by threats against him and his family after stepping down from office; he intended to murder the Dalai Lama in order to resume power.

The Demo, his brother, and Nyaktrul all died in custody—almost certainly as a result of their treatment. Although some argued that the Demo’s political enemies framed him, the Dalai Lama later told British-Indian Tibetologist Charles Bell that he believed that the Demo had participated in the plot.

The Dalai Lama forbade the identification of the Demo’s reincarnation, but several years later his followers did so anyway—in the person of the Dalai Lama’s own nephew, Trinle Rabgye, whom the Dalai Lama allowed to be confirmed as the 10th Demo.

Alexander Gardner has a PhD from the University of Michigan in Buddhist Studies and serves as the Associate Director of the Rubin Foundation.