If you look on a map, you’ll see that the spread of Mahayana Buddhism matches places where the winters are bad and it snows a lot. Why? In warmer climates in India, monks could live in the forest, taking refuge in temporary structures to wait out the rainy season. But in northern climates, the long winters demanded better protection, so home-leaving monks had only two choices: they could live in a cave or in a monastery.

The monasteries, however, were usually built with royal money and permission. As I wrote about in my last blog, a king wanted to limit the number of people who were avoiding military service, paying taxes, making babies, and contributing to the economy. So the emperors put restrictions on who and how many people could “leave home,” establishing means to filter out draft-dodgers from genuine monks. To be “official monks,” for instance, wannabes would have to pass tough exams like reciting the entire Lotus Sutra from memory. Another restriction demanded that monks take their precepts only from preceptors appointed by the court, and do so only on “official” ordination platforms.

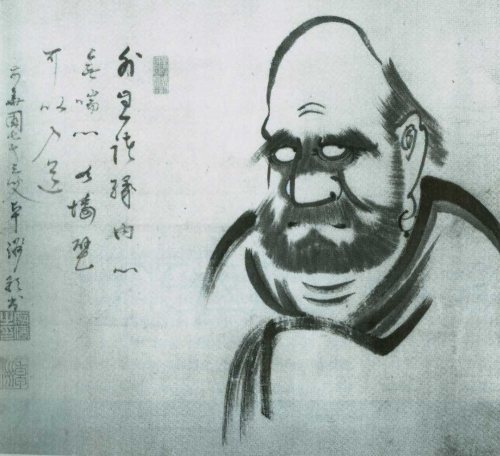

The result of all this was that certain doctrines and practices unique to Mahayana Buddhism appear to have been nurtured and promoted by kings as part of the package a monk had to accept to live in a monastery. Certain key emperors in this story, like the Northern Wei Dynasty Emperor Xiao Wendi, personally wrote and revised the Buddhist precepts and conferred them on monks he deemed suitable. Xiao Wendi even declared himself to be the Tathagata, and thus fully qualified to say who was and was not one of his true followers. It was not a coincidence that three rebellions broke out against this emperor and his “imperial Buddhism,” led by itinerant monks who were not part of the official Buddhist establishment. Zen Buddhism in particular appears to have been a profound reaction against this strain of imperial Buddhism. (This is why Bodhidharma is said to have practiced in a cave, and not in the imperially established Shaolin monastery that was only a mile or so away. It was a place to get out of the snow and still avoid an emperor’s megalomania.)

But getting back to the original question: why does Mahayana Buddhism correspond to Asia’s snow zone? The answer may be that there simply weren’t enough proper caves to go around. Monks needing suitable winter quarters, wittingly or not, had to accept some of the Mahayana doctrines that emperors expounded.

—Andy Ferguson

This post is part of author and scholar Andy Ferguson’s new “Consider the Source” series. As an old Chinese saying goes, “When drinking water, consider the source.” In the coming weeks, Ferguson will ask and answer seemingly simple (but in the end, profound) questions about the “source” of East Asian Buddhism, weaving a tale of both spiritual inspiration and political intrigue.

This fall, Tricycle will be traveling to the source itself, China, in a special pilgrimage led by Ferguson and abbot of the Village Zendo Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara. Want to come with us? Click here for more information.