Biography and autobiography in Tibet are important sources for both education and inspiration. Tibetans have kept such meticulous records of their teachers that thousands of names are known and discussed in a wide range of biographical material. All these names, all these lives—it can be a little overwhelming. The authors involved in the Treasury of Lives are currently mining the primary sources to provide English-language biographies of every known religious teacher from Tibet and the Himalaya, all of which are organized for easy searching and browsing. Every Tuesday on the Tricycle blog, we will highlight and reflect on important, interesting, eccentric, surprising and beautiful stories found within this rich literary tradition.

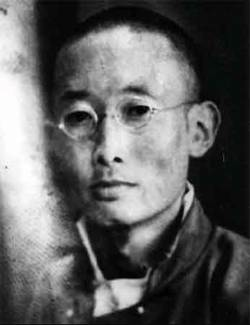

Gendun Chopel

Gendun Chopel was a philosopher, painter, scholar, and activist. He lived a fascinating life, the details of which reflect the tumultuous and transformative time in which he lived—born just months before Colonel Younghusband rode across the southern Himalayan border, forever rupturing the fragile skin of the Tibetan border, and passing away just a few weeks after Chinese soldiers marched around the heart of Lhasa.

Gendun Chopel was born in the spring of 1903 near Lake Kokonor in Amdo, where his parents were returning from pilgrimage to central Tibet. He spent the first ten years of his life studying under the prolific yogi-poet Zhabkar Tsokdruk Rangdrol (1781–1851) in Rebkong. Like Pelden Tashi (1688–1742), the founder of the Ngakmang lineages, Gendun Chopel navigated between the Nyingma and Geluk traditions, maintaining a strong nonsectarian view throughout his life.

At the age of 13 he went to the Geluk monastery Ditsa, and five years later attended the monastic university of Labrang Tashikhyil, where he stayed for six years. During this time he earned a reputation as an innovative thinker and unbeatable debater. He also learned the rudiments of English and clock mechanics from a Christian missionary from America, Marion Griebenow, who taught him the skills necessary to make mechanical birds and boats.

Gendun Chopel’s iconoclastic views clashed with Gelukpa orthodoxy at Labrang, and in 1927, at the age of 25, he set out for Lhasa, travelling for three months on foot with a caravan of pilgrims. Once in Lhasa, Gendun Chopel entered the Gomang College at Drepung Monastery to study with Geshe Sherab Gyatso (1884–1968), one of the most revered Geluk scholars of his time.

It was during this time that Gendun Chopel found his natural talent for painting. His life-like portraits earned him a living in Lhasa, and a reputation amongst the Lhasa nobility. Some consider Gendun Chopel the first professional contemporary artist of Tibet.

It was during this time that Gendun Chopel found his natural talent for painting. His life-like portraits earned him a living in Lhasa, and a reputation amongst the Lhasa nobility. Some consider Gendun Chopel the first professional contemporary artist of Tibet.

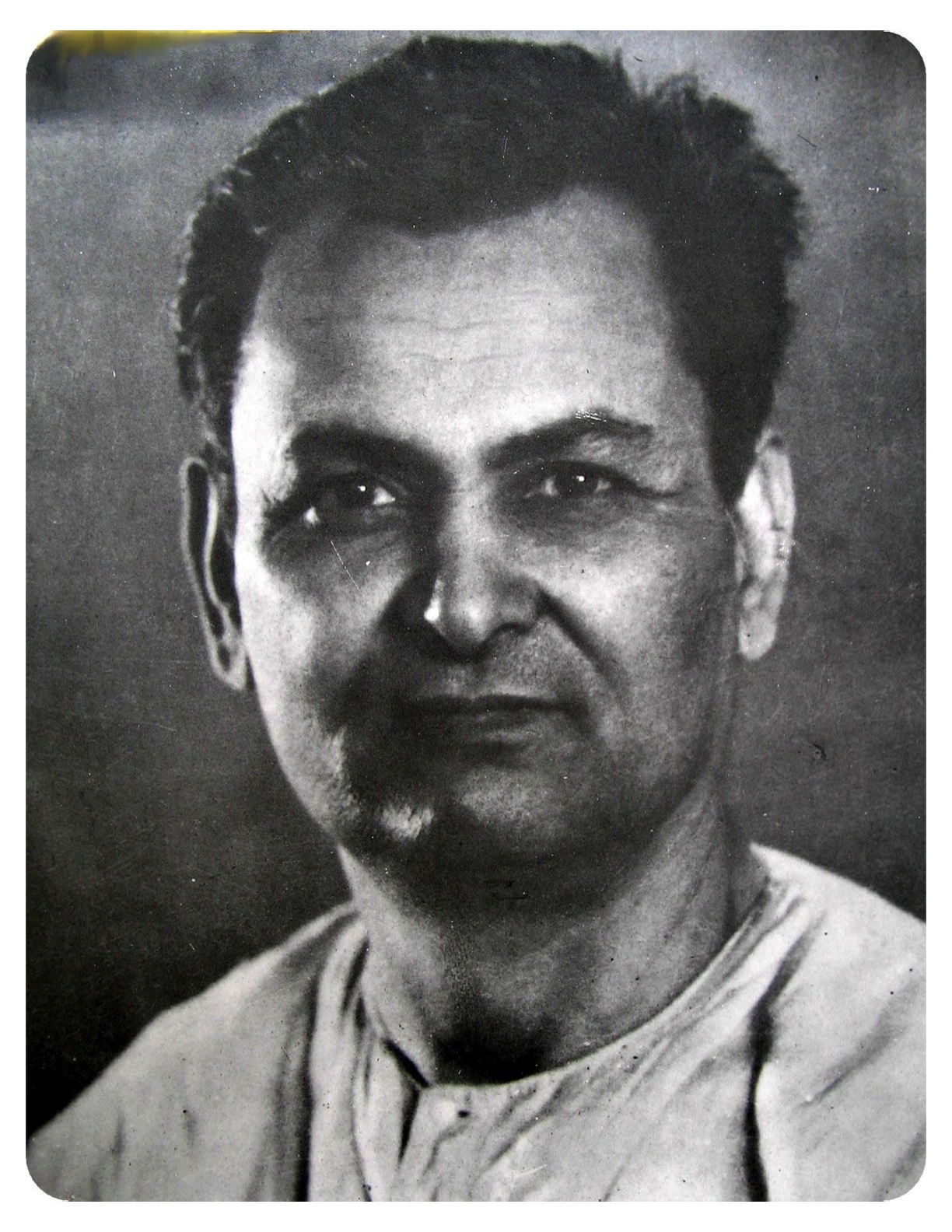

Through his close kinship with Sherab Gyatso, he became increasingly aware of the political and social movements outside of Tibet. In addition to having a wide network of friends and contacts, Geshe Sherab owned one of the only private radios in the whole country, broadcasting the latest news on Mao Zedong. When in Lhasa, Gendun Chopel would stop in and meet with Geshe Sherab, and receive word of recent international news. There he met Rahul Sankrityayan, a Hindu ascetic and Buddhist scholar on his second visit to Tibet. Sankrityayan was an adventurer, a prolific writer, a member of the Communist Party of India, and a founding member of the Indian Peasants Union. The two got along famously, appreciating in each other a mutual love of learning and progressive discourse. Gendun Chopel eventually travelled to India with Sankrityayan, with the intention of seeing the Buddhist holy sites of India.

Over the next twelve years he travelled throughout South Asia. His passionate curiosity was well satiated in India: studying Sanskrit, improving his English, becoming familiar with the Theravada Vinaya and studying Buddhist archeological sites. In addition, he became familiar with Indian culture, customs, and the movement for Indian independence, including Mahatma Gandhi’s khadi or “home-spun” economy. His travels brought him into contact with a number of Western Tibetologists and Indophiles including Nicolas Roerich, who introduced Chopel to Sufi mysticism, Russian orthodox Christianity, Schopenhauer, Kant and Marx. Gendun Chopel began to publish articles, questioning the accuracy of the traditional Tibetan views of history, world geography, and the origin of Tibetan writing.

Over the next twelve years he travelled throughout South Asia. His passionate curiosity was well satiated in India: studying Sanskrit, improving his English, becoming familiar with the Theravada Vinaya and studying Buddhist archeological sites. In addition, he became familiar with Indian culture, customs, and the movement for Indian independence, including Mahatma Gandhi’s khadi or “home-spun” economy. His travels brought him into contact with a number of Western Tibetologists and Indophiles including Nicolas Roerich, who introduced Chopel to Sufi mysticism, Russian orthodox Christianity, Schopenhauer, Kant and Marx. Gendun Chopel began to publish articles, questioning the accuracy of the traditional Tibetan views of history, world geography, and the origin of Tibetan writing.

During his 12 years in South Asia, Gendun Chopel went to Kalimpong for most summers. There he would work with Tibet Mirror founding editor Tharchin Babu, contributing articles to his far-reaching Tibetan-language publication. Kalimpong in the 1940s was the seat of a group of Tibetan exiled dissidents—with whom Gendun Chopel associated—who advocated for the overthrow of the Ganden Podrang government of the Dalai Lamas and cultural reform in Tibet.

Back in Lhasa, Chopel was a rare breed: his knowledge of the outside world, his new ideas in regard to Tibet, and his immense learning and travel amounted to great popularity amongst progressive families and nobility in Lhasa. He was consulted on many subjects and began to teach grammar and art to notable individuals of the religious and social elite. He also compiled his research, notes, and work from the many years spent in South Asia.

In 1947, when the current Dalai Lama was only 13 and two regents, who were in conflict, ruled Tibet, Gendun Chopel became the focus of religious extremism and orthodoxy. He was arrested and accused of being a Chinese communist spy. His research material and work were confiscated, and he was imprisoned for about two years.

After his release in 1949 or 1950, he created one of his greatest philosophical works: Adornment for Nagarjuna’s Thought. The work was highly controversial amongst orthodox Geluk leaders, causing uproar in Lhasa. It was, however, eventually printed in Kalimpong.

In October 1951, Gendun Chopel developed severe edema, which ended his life just a month after he watched, with a heavy heart, Chinese soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army walk through the streets of Lhasa, a sight that no doubt shattered his dreams of a modernized, autonomous Tibet.