Buddha Buzz will be short and sweet today, as this afternoon the Tricycle office was hosting Thai forest monk and abbot of Metta Forest Monastery Thanissaro Bhikkhu. He recently published a really excellent guide to meditation called With Each and Every Breath. Like all of his books, it is free to download. You can do so here. (And personally, I highly encourage you to do so. It’s good stuff.)

Thanissaro Bhikkhu with Editorial Assistant Alex Caring-Lobel, Associate Editor Emma Varvaloucas, Managing Editor Rachel Hiles, Editor and Publisher James Shaheen, and Digital Media Coordinator Andrew Gladstone

As I’m sure you already know, this week we saw some shakeups in world leadership. There’s a new pope, Pope Francis I, a Jesuit from Buenos Aires who, if Wikipedia is to be believed, is the first non-European pope in 1,282 years. I’m not so excited about his views on abortion and LGBTQ rights—he described the pro-choice movement as a “culture of death” and opposes same-sex marriage—but we are talking about the Catholic church, so it’s not like I can realistically feign surprise. I haven’t turned up anything about Pope Francis’ views on Buddhism or his relationship with Buddhists, but he does say that he is open to dialogue with other religious faiths, so we’ll have to wait and see about that. I bet a nice photo of him and HHDL hanging out will surface on the Internet soon.

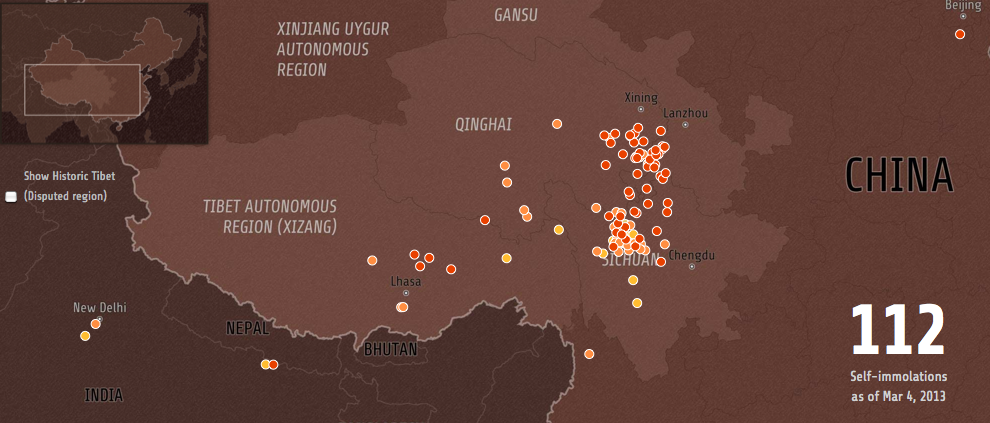

On Thursday Xi Jinping became China’s new president, replacing Hu Jintao in a once-a-decade power shift in the Communist party. Coincidentally, last Sunday was Tibetan Uprising Day, which commemorates the 1959 Tibetan rebellion against Chinese occupation that led to HHDL’s escape into India. In honor of the occasion, Al Jazeera English has created what is known around the Tricycle office as “the most depressing infographic ever”: an interactive visualization that shows the increasing number of Tibetan self-immolations in recent years. The current count is at 112.

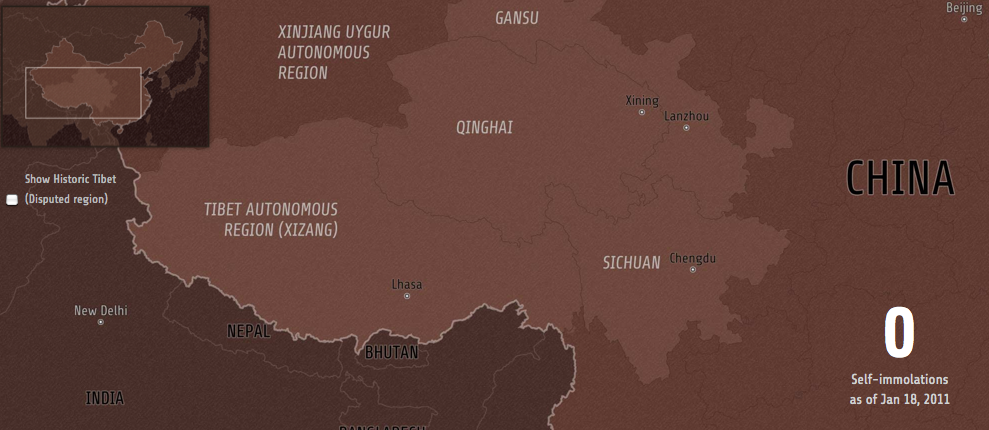

Number of self immolations as of January 1, 2011

Number of self immolations as of March 4, 2013

Over at Vice, Michael Muhammad Knight has written a compelling piece called “The Problem with White Converts.” (If I’m not mistaken, Knight is a white convert, so we know at least that the guy has a healthy sense of irony.) The article is partly about Henry Steel Olcott, a nineteenth century Theosophist, known as the United States’ first Buddhist convert. This isn’t entirely true, but Olcott was one of the earliest—and most talkative—Western proponents of Buddhism. Knight writes about him:

Olcott thus took part in a Euro-American reinvention of the Buddha as a modern empiricist philosopher and argued that the Buddha’s teachings were based on science, rather than supernatural claims, and that Buddhism opposed rituals, ceremonies, idolatry, and belief in miracles. This was not a Buddhism based on Olcott’s encounters with Buddhist tradition as people actually lived it in the world, but only the “true Buddhism” that he found in the Buddha’s original message. Olcott’s “true Buddhism” was necessarily contrasted with what he saw as the superstitions and corruptions of uneducated, uncivilized Buddhist masses. In other words, Olcott converted to Buddhism and then claimed to understand the Buddha better than every other Buddhist on the planet.

Sound familiar? We do, unfortunately, see this same idea played out in convert Buddhist communities and literature all the time. We assume that we can separate the “real Buddhism” from its various Asian “cultural containers,” like we’re not coming at it with any cultural baggage of our own. Or as Knight handily summarizes the problem:

When people assume that “religion” and “culture” exist as two separate categories, culture is then seen as an obstacle to knowing religion. In this view, what born-and-raised members of a religious tradition possess cannot be the religion in its pure, text-based essence, but only a mixture of that essence with local customs and innovated traditions. The convert (especially the white convert, who claims universality, supreme objectivity, and isolation from history, unlike the black convert, whose conversion is read as a response to history), imagined as coming from a place outside culture, becomes privileged as the owner of truth and authenticity. People forget that these white guys aren’t simply extracting “true” meaning from the text, but bringing their own cultural baggage and injecting it into the words.

If you couldn’t tell, Knight is known in Islamic circles as being a bit of a provocateur…