Buddhist practice and Buddhist art have been inseparable in the Himalayas ever since Buddhism arrived to the region in the eighth century. But for the casual observer it can be difficult to make sense of the complex iconography. Not to worry—Himalayan art scholar Jeff Watt is here to help. In this “Himalayan Buddhist Art 101” series, Jeff is making sense of this rich artistic tradition by presenting weekly images from the Himalayan Art Resources archives and explaining their roles in the Buddhist tradition.

Himalayan Buddhist Art 101: Why Paintings Are Made, Part 1

There is an almost universal belief among Buddhist practitioners that all old Himalayan paintings are made from a pure motivation and based in spiritual or religious practice. Many are, but not all. There are many different reasons and motivations for creating paintings. These reasons are often religious, but they are also rooted in local customs.

Paintings can be commissioned as gifts, ritual objects, practice support, or for the purposes of religious commitment, storytelling, and biography. In the Himalayan and Tibetan traditions it is common to have a painting commissioned in memory of a deceased family member or close teacher.

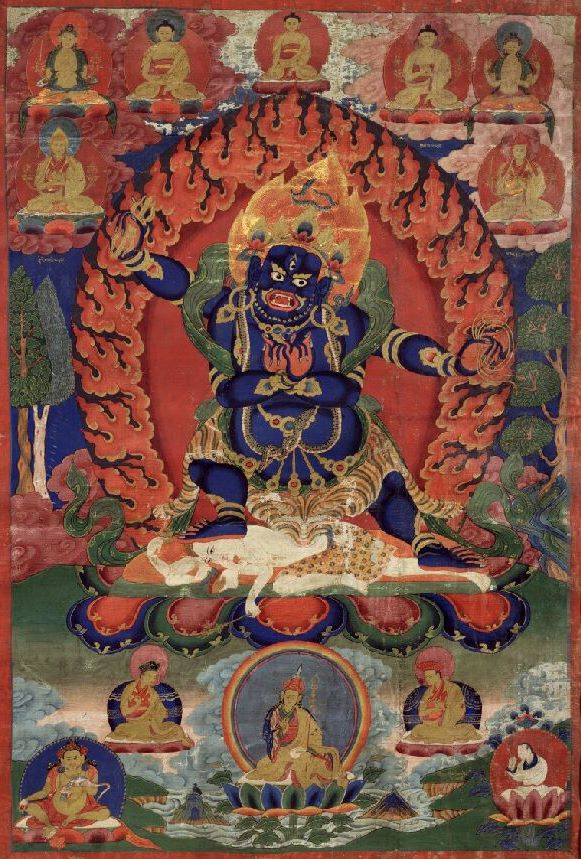

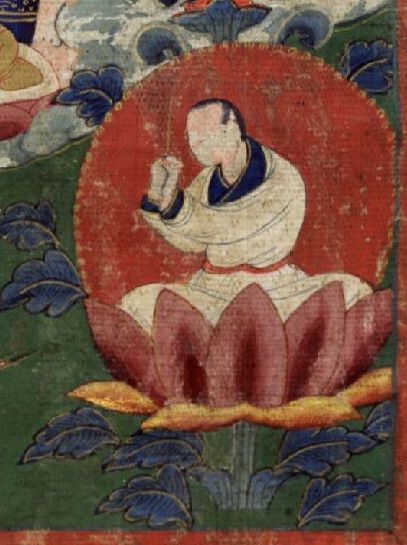

The first example of a memorial painting depicts a large central image of Vajrapani surrounded by teachers representing all the major traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. The small kneeling figure in the bottom-right corner, dressed in white and seated atop a pink lotus, is the deceased. The painting was created and dedicated by the family of the unidentified deceased family member. Once completed, a commemorative painting such as this is typically hung in the family home or chapel.

The choice of a central figure for compositions like these is either based on the favored deity of the deceased or chosen through divination after his or her death. Commemorative paintings for political leaders and religious teachers tend to be far more lavish and often consist of multiple compositions including sculpture, all offered during elaborate funerary rituals.

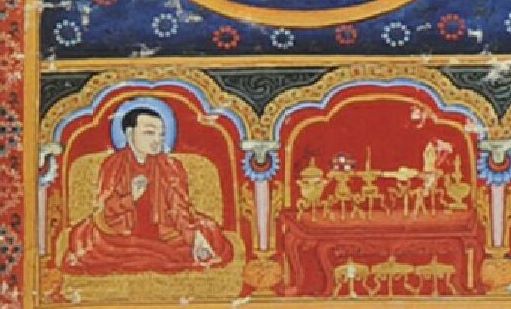

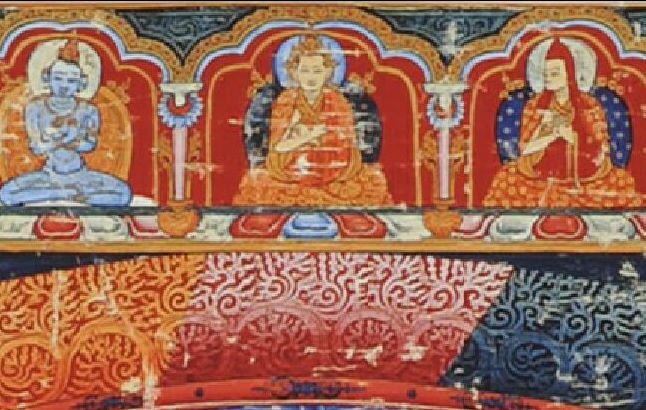

The second example is a mandala painting that belongs to a set of approximately 27 compositions created in commemoration of Lama Dampa Sonam Gyaltsen (1312–1375). In this painting he wears a crown and monastic clothing, with hands crossed at the heart. His image is situated at the top-center of each and every composition. The donor figure in the set is Tai Situ Jangchub Gyaltsen, founder of the Phagdru Dynasty of Tibet in the 14th century. Jangchub Gyaltsen is located at the bottom-right or -left corner of each of the 27 compositions.

Many of the Himalayan-style paintings that populate the museums and private collections of the world are memorial paintings. When viewing a composition, look for a small figure wearing white with hands folded at the heart, perhaps seated atop a lotus. These signs can be used to identify the composition as a memorial painting.