Biography and autobiography in Tibet are important sources for both education and inspiration. Tibetans have kept such meticulous records of their teachers that thousands of names are known and discussed in a wide range of biographical material. All these names, all these lives—it can be a little overwhelming. The authors involved in the Treasury of Lives are currently mining the primary sources to provide English-language biographies of every known religious teacher from Tibet and the Himalaya, all of which are organized for easy searching and browsing. Every Tuesday on the Tricycle blog, we will highlight and reflect on important, interesting, eccentric, surprising and beautiful stories found within this rich literary tradition.

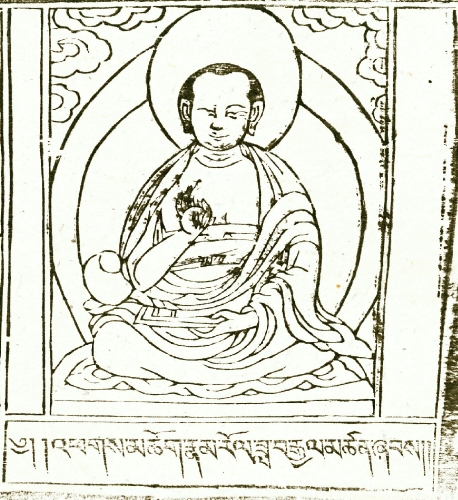

The Tongkhor Incarnation Line

Tibetan Buddhism is famous for the institution of recognized reincarnations, known in Tibet as tulku, a Tibetan rendering of the Sanskrit nirmanakaya, or “emanation body.” The practice of identifying a child as the reincarnation of a deceased master is said to have begun in the thirteenth century, and is a practice that is well-founded in Buddhist doctrine—all beings reincarnate, after all. The Dalai Lamas and the Karmapas might be well-known, but there are quite literally thousands of incarnation lines across Tibet and Inner Asian regions.

Although the practice is universally accepted in Tibetan Buddhist communities, incarnation lines themselves are not without controversy, as evidenced by the current conflict over the correct identity of the Seventeenth Karmapa (there are currently five men who claim the title). One incarnation line, the Tongkhor lamas, is curious for both the fact that it split, producing two separate incarnation streams of Tongkhor lamas, and by the remarkable means by which the Fourth Tongkhor came into being—through the reanimation of a corpse!

The First Tongkhor, Dawa Gyeltsen (1476-1556) was born into a poor family in the border region of Amdo and China, where he received his early religious education in the new Geluk tradition. He later moved to Lhasa and studied at Sera Monastery, returning to Amdo where he spent many years in a cave. At some point he went down to Kham and converted a small Bon institution to Geluk. He then established a small monastery that he named Tashilhunpo, after the monastery in Shigatse established by the First Dalai Lama in 1447. Following his death, a young boy, Yonten Gyatso (1557-1587) was recognized as his reincarnation and installed at Tashilhunpo.

After the death of the Third Tongkhor, Gyelwa Gyatso (1588-1639), things got strange. According to tradition, a recently deceased seventeen-year old boy of mixed Tibetan and Chinese heritage, while being carried to his funeral, suddenly sat up and declared that he was the Tongkhor lama. Quite reasonably thought to be a zombie, the Chinese army was called in to destroy him. The boy emerged from the assault unharmed, convincing everyone that he was indeed the reincarnation of Gyelwa Gyatso. It was understood that Gyelwa Gyatso had employed the technique of transferring consciousness, drongjuk, into the boy’s corpse at the moment of his own death.

The identity of the young man, who was given the name Dogyu Gyatso by local lamas, was later affirmed and taught by the Fourth Panchen Lama, Lobzang Chokyi Gyeltsen (1570-1662), and the Fifth Dalai Lama, Ngawang Lobzang Gyatso (1617-1682). After returning east, he created a new Geluk monastery called Tongkhor Ganden Chokhor Ling in the Tongkhor region of Amdo. It would seem that this institution developed quite quickly, and in competition with Tashilhunpo down in Kham, for following the death of the Fifth Tongkhor, Ngawang Sonam Gyatso (1684-1752), both communities put forward their own reincarnations. There were thus two Sixth Tongkhor lamas: Ngawang Jamyang Tendzin Gyatso (1753-1798) and Jampel Gendun Gyatso (1754-1803). The two lines have continued to today, and the current incarnations are said to get along quite well.

Meet your Treasury of Lives blogger: Alexander Gardner has a PhD from the University of Michigan in Buddhist Studies and serves as the Associate Director of the Rubin Foundation.

Meet your Treasury of Lives blogger: Alexander Gardner has a PhD from the University of Michigan in Buddhist Studies and serves as the Associate Director of the Rubin Foundation.