A lot has been written in Tricycle over the years about the importance of sangha. Here on tricycle.com, we’ve endeavored to provide our members with not only a wealth of information about Buddhist practice and teachings but also with a sense of community. To that end, we also host a Tricycle community page, which you can visit at community.tricycle.com.

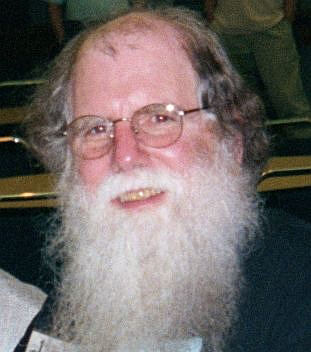

Today we’re sharing an interview with a standout member from our Tricycle community, Mark Drew, who lives in Des Moines, Iowa. Though he’s wary of becoming an official, card-carrying Buddhist (read about his perspective on the seriousness of taking refuge below), he’s an active and valued member of our online sangha. Diagnosed with multiple sclerosis when he was 39, Mark, now 67, has “done more solitary time than a lot of monks in cells or prisoners in jails.” Below, Mark talks about life with MS, his views on the Pali canon, and more.

—Emma Varvaloucas

When did you join the Tricycle Ning community site? When Tricycle first got the website up they sent me an e-mail telling me about it, basically just enlisting everybody to rush right over and sign up. And I did! So I was probably one of the first people who was ever on Tricycle online.

When did you join the Tricycle Ning community site? When Tricycle first got the website up they sent me an e-mail telling me about it, basically just enlisting everybody to rush right over and sign up. And I did! So I was probably one of the first people who was ever on Tricycle online.

I was reading on your Ning profile that you don’t consider yourself to be a Buddhist. No, I would not consider myself to be a practicing Buddhist. I’ve never taken refuge or anything like that. We are all products of our pasts, and taking refuge would be fulfilling my parents’ nightmares. I would have to actually truly believe Buddhism, you know, before I did it. I wouldn’t do it as a casual thing like moving from one church to another, or from one congregation to another. I would never do that. I would have to be totally convinced that that was absolutely the only thing in the world before I would take refuge. People may not look at it this way, but taking refuge is a vow. At the very least it’s a commitment. So to me it would be almost like signing a contract. And I wouldn’t do that until I was willing to fulfill my end of it.

What do you mean by saying that taking refuge is a vow? What is one vowing and to whom is one vowing to, in your opinion? Taking refuge is a formula for a commitment that is precisely prescribed: “I take refuge in the Buddha, the Dhamma and the Sangha.” Merriam-Webster defines vow as “a solemn promise or assertion; specifically: one by which a person is bound to an act, service, or condition.” That is precisely what I perceive taking refuge in the Three Jewels to be. It is a commitment, whether assent is given publicly or internally. One accepts a concept or persona with more or less defined parameters. One crosses an intellectual line in the sand that surpasses a mere philosophical disposition or agreement to a wholehearted and committed invocation of both benefit and responsibility.

The vow is made foremost to one’s self and expresses a level of moral and intellectual agreement to a level or degree not previously assented to; secondly, if publicly expressed, a representation is made to the world in general and often to a specific sangha—if the taking of refuge is indeed made upon membership in a sangha, then one would assume that one also vows to uphold the Five Precepts in the manner as defined by that sangha. To take refuge is to cross a moral bridge which one should not lightly transverse. However, like many similar vows and agreements, I fear that in Western society the sanctity of the original commitment is ignored and such vows are lightly entered into and easily voided. I would further submit that naming oneself as a Buddhist in a Western context for many carries no perceived responsibility or commitment and is intellectually indistinguishable from a myriad of other New Age and/or “self-help” philosophies.

I understand you have MS? When were you diagnosed? Gee, when I was 39. I’m 67 now, so you do the math—I’m slow. Before that they told me for four or five years that I was having transient ischemic attacks. I’ve had problems since my late twenties and early thirties. But they didn’t ever diagnose me until I was 39, when they finally nailed me down and got a spinal tap on me.

Did your life changed dramatically with the diagnosis? With the diagnosis, no. Living changed a whole lot. The diagnosis, they give you the diagnosis and they tell you, “now, don’t worry about it, just live your life like you always did.” No, when they give you the diagnosis nothing changes from the day before. It’s five years on down the line that your life changes, if you know what I’m saying.

Has having MS affected the way that you practice Buddhism? I practice nothing. There are very few pros in MS. If anything, it would be having a lot of time. There were 20 years when my wife was still working ten-hour days that I was basically alone most of the time. So I’ve done more solitary time than a lot of monks in cells or prisoners in jails. That’s just a byproduct of MS. It gives you a lot of time to think about things.

So I’m sure you can say that you’re comfortable with yourself, with being alone by yourself. Not many people can truly say that. You don’t have a whole bunch of options. That’s the reason why I’m on Trike so much—it’s a way to interact with people. The computer is kind of my social outlet, and it was even before the days of Trike. The computer is my window onto the world, as it were.

And it’s your online sangha. Yes, exactly. I live in Des Moines, but have I explored the Buddhist scene there? No. I mean obviously I know where Buddhists—I know where they are. I just have no way to interact with them face to face. So if you want to put it in that terminology, that’s exactly right. I am functionally a shut-in and Trike is my only means of associating with like-minded individuals (within this context that is; medical folk I meet all the time and they all pass as best-est buddies in the whole wide world). The most obvious advantage to a group such as Trike is its availability—all one has to do is log in and there you go.

The corollary to availability is the impersonal aspect of the interactions. One may become emotionally invested with the personae presented to you online but at the end of the day we are privy to even less of the actual person than we are in the real world inasmuch as all physical “tells” are impossible to detect. In cyberspace no one may hear you scream, but conversely one can’t really see you smile, slouch your shoulders, or roll your eyes.

You are very active on the Tricycle boards as well, often defending your position that Buddhists should stick with the Pali canon and not go further than that. Most people on Trike give me crap for being such a one-note person and being so close-minded. But the Pali canon is the only thing that makes intellectual sense to me.

See, I come from a very, very conservative Christian background that’s always had Anabaptist roots in it. Historically, we’re people of the word. I guess you don’t get to be my age and just throw that away. People think that whatever is right for you is right. But you can’t really sell that in the market of ideas. For instance, a lot of stuff that I see on Trike is about self and no-self. That’s not in the Pali canon. In fact, metaphysics across the board is rejected. The Pali canon says that those sorts of arguments or concerns are basically counterproductive to your practice. It’s like in the Buddha’s dialogue with Vacchagotta. Vacchagotta came and asked a question on self. And the Buddha wouldn’t answer it.

You have on your Ning profile that you have 66 years’ worth of stories. That’s up to 67 now. And some of them are even true.

Can you tell me a few of them? If I were to tell you stories I would probably tell you a story that related back to the sixties. That was a pivotal point in my era. We were heavily involved in anti-war activities. I was in the security service, and when I got out I became a conscientious objector and was discharged. I had to sign away all of my benefits, my rights. At the time the anti-war groups were being infiltrated by cops; there were a lot of bombings here in Des Moines and a lot of people went to jail. It was a time, and it was pivotal in my life.

Why was it so pivotal in your life? You know, every era, every generation, has a movement, and you can either watch it go by or you can take part in it. And that was the wave of my era. There were important issues. People were dying. You had to do things. You had to put something on the line, because it was important. The world was up for sale and you had to do something.

And then I got MS and stuff and now I sit in a room all day. It was the time that I was out there and we were trying to do something. You couldn’t stand by. You were either a part of the problem or part of the solution. And we were doing everything we could to be part of the solution. I don’t know if we won or not—I guess not.

That’s actually all the questions I wanted to ask you. Aw, you’re no fun.