Buddhist practice and Buddhist art have been inseparable in the Himalayas ever since Buddhism arrived to the region in the eighth century. But for the casual observer it can be difficult to make sense of the complex iconography. Not to worry—Himalayan art scholar Jeff Watt is here to help. In this “Himalayan Buddhist Art 101” series, Jeff is making sense of this rich artistic tradition by presenting weekly images from the Himalayan Art Resources archives and explaining their roles in the Buddhist tradition. This week Jeff explores the multifaceted Avalokiteshvara in Himalayan Buddhist art.

Himalayan Art 101: Avalokiteshvara

Avalokiteshvara is figured in the Mahayana sutras along with a number of other exceptional and other-worldly students of Shakyamuni Buddha, such as Manjushri, Vajrapani, and Maitreya. In the sutra literature these supporting characters often perform the role of interlocutor, asking the tough questions that the others in the group wonder but dare not ask. As a group, these exceptional students are called bodhisattvas—the hallmark Mahayana Buddhism.

The sutras contain many names and references to individual bodhisattvas. Vajrayana Buddhism formalizes this register of bodhisattvas and pares it down to just eight (though in rare situations, it has been expanded to sixteen). Avalokiteshvara is certainly one of the most prominent of these bodhisattvas, along with Manjushri and Vajrapani. This list is Vajrayana’s condensation of the longer list of Mahayana Buddhist figures. The eight bodhisattvas are commonly depicted in Himalayan and Tibetan Buddhist art to represent both the principal bodhisattvas of the Mahayana sutras and the “semi-enlightened” sangha of Shakyamuni Buddha.

The sutras contain many names and references to individual bodhisattvas. Vajrayana Buddhism formalizes this register of bodhisattvas and pares it down to just eight (though in rare situations, it has been expanded to sixteen). Avalokiteshvara is certainly one of the most prominent of these bodhisattvas, along with Manjushri and Vajrapani. This list is Vajrayana’s condensation of the longer list of Mahayana Buddhist figures. The eight bodhisattvas are commonly depicted in Himalayan and Tibetan Buddhist art to represent both the principal bodhisattvas of the Mahayana sutras and the “semi-enlightened” sangha of Shakyamuni Buddha.

In the practice of Vajrayana Buddhism, Avalokiteshvara, like Majushri and Vajrapani, is considered a Buddha. These bodhisattvas are also looked upon as embodiments of different aspects of the enlightened ones: Avalokiteshvara is the embodiment of the compassion of all buddhas, Manjushri, the wisdom, and Vajrapani, their power and activity.

Tantric literature mentions literally hundreds of different meditational forms of Avalokiteshvara, which include very specific forms in which he functions as a wealth deity or power deity. He can be peaceful in appearance or very wrathful, with multiple heads and arms. There are even frightening forms of Avalokiteshvara as a fierce protector. One initiation in a Tibetan Buddhist tradition corresponds to such a form, and is not given to the general public due to its intense wrathfulness. Meditational forms of the deity vary from straightforward to extremely complex configurations consisting of elaborate mandala and palace descriptions, and large retinues filling the sacred mandala space. Such elaborate meditational systems can also have associated yearly festivals and musical and dance rituals.

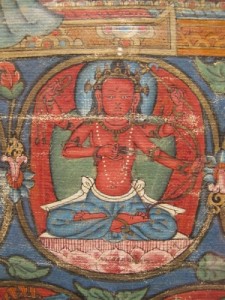

The three examples of Avalokiteshvara shown here begin with Simhanada, white in color and riding a lion. Simhanada represents compassion and the overcoming of disease and ailments. The second form is a power Lokeshvara, red in color, seated, possessing four arms. The third is the Lord of the World Lokeshvara, who is blue in colour, very wrathful, possessing five faces and twelve arms. These examples constitute only a miniscule sampling of the hundreds of different meditational forms of Avalokiteshvara.

The three examples of Avalokiteshvara shown here begin with Simhanada, white in color and riding a lion. Simhanada represents compassion and the overcoming of disease and ailments. The second form is a power Lokeshvara, red in color, seated, possessing four arms. The third is the Lord of the World Lokeshvara, who is blue in colour, very wrathful, possessing five faces and twelve arms. These examples constitute only a miniscule sampling of the hundreds of different meditational forms of Avalokiteshvara.

Who is Avalokiteshvara? The simplest explanation is that he is an important supporting character in the disourses of the Buddha, a personification of compassion, and a figure who can be defined differently between the Mahayana sutras and Vajrayana tantric literature.

Learn more about Avalokiteshvara and view these paintings and more in full size at Himalayan Art Resources.