THE MOUNTAIN SPIRIT Edited by Michael Charles Tobias and Harold Drasdo The Overlook Press: Woodstock, 1979. 264 pp., $14.95 (paper).

SACRED MOUNTAINS IN CHINESE ART by Kiyohiko Munakata The University of illinois Press: Urbana and Chicago, 1991. 200 pp., $39.95 (paper).

SACRED MOUNTAINS OF THE WORLD by Edwin Sernbaum Sierra Club Books: San Francisco, 1990. 291 pp., $50.00 (cloth).

MOUNTAINS generate paradoxical words in humans as naturally and ceaselessly, it seems, as they generate clouds, mist, snow, ice, and headwaters. Why do we climb mountains? Because they’re there, said mountain-master Mallory. And why do we write, paint, and photograph mountains? Because we’re here.

The Mountain Spirit begins with an essay on “Modesty and the Conquest of Mountains” by Arne Naess, the Norwegian philosopher of Deep Ecology. The essay concludes with modest, plainspoken common sense:

As I see it, modesty is of little value if it is not. . . a consequence of a way of understanding ourselves as part of nature in a wide sense of the term. This way is such that the smaller we come to feel ourselves compared to the mountain, the nearer we come to participating in its greatness. I do not know why this is so.

The Mountain Spirit then goes on to offer a wide range of original essays and translations, mixing mountaineering, scholarship, literature, memoir, and art—black-and-white photographs and paintings, both Eastern and Western—so that all the various elements inform and enrich each other. Often this happens in the same essay. In “A Politics of Alpinism,” for example, Bernard Amy asks,

How can we create inner adventure out of external technique while keeping a delicate balance between extremes of mysticism and frenzied materialism?

and suggests a solution drawn from Zen Buddhism and the poetic theory of Roman Jakobson. Again, in “Bouldering: A Mystical Art Form,” John Gill says that “the boulderer is an artist who seeks self- realization through kinesthetic awareness.”

There are sobering, cautionary accounts as well. Photographer Galen Rowell writes a gripping account about nearly dying in a freak blizzard on an ascent of Yosemite’s El Capitan. And co-editor Harold Drasdo confesses—after reviewing the great variety of images of mountains and ascent in spiritual and literary works—that

it must be admitted that the mountain and the halt at the summit do not often provoke such exalted claims in those who know them best. Bad weather, the risks of the descent, exhaustion, familiarity with the mountain scene, take the edge off the culminating moments of a climb.

There are many other worthwhile byways here: an eerie “Fragment: The Ladders of the Lost Ones,” by Samuel Beckett; Michael Tobias’ survey, “A History of Imagination in Wilderness,” which stretches from the Paleolithic cave painters to Shelley and John Muir; and H. Bryan Earhart’s fascinating essay on the aesthetics of Shugendo, the syncretic shinto-Buddhist “Mountain Religion” of Japan.

But the high point, the summit, for me is Carl Bielefeldt’s introduction and translation of Dogen’s Sansuikyo, the Mountains and Waters Sutra. Indeed, it was because of this translation—first published here—that I opened this book in 1979 and read those thunderous opening lines: “These mountains and rivers of the present are the actualization of the word of the ancient Buddhas.” Since then, I have wandered many miles in the Mountains and Waters Sutra. Indeed, Dogen’s sutra is like one of those especially challenging mountains that you go back to climb again and again, getting lost in thickets, sucked in by swirling mist, stumbling purely by accident onto a sudden opening that reveals great vistas—which close, just as suddenly, as another storm rolls in from nowhere.

Dogen’s mountains tie the tongue and shatter the paradox of mountain and spirit. They are hidden—”mountains hidden in jewels, mountains hidden in marshes, mountains hidden in the sky, mountains hidden in mountains”—and obvious, right under our feet:

The blue mountains are neither sentient nor insentient: the self is neither sentient nor insentient. Therefore, we can have no doubts about these blue mountains walking.

These hidden mountains walk, as well, through the scrolls of the Chinese landscape painters. This great tradition is the subject of Sacred Mountains in Chinese Art, a catalogue of an exhibition that appeared at the Krannert Art Museum of the University of Illinois and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Professor Munakata has written a thorough, scholarly commentary revealing the “steady process of evolution” of the image of the sacred mountain in China over two thousand years—as “an unapproachable mystical realm developed into that of a benevolent, accessible entity from whose divine power man may seek benefits.”

Most of the human figures in these paintings remind one of Naess’ “modesty.” They’re all the right scale, which is to say small if not minuscule, and so they fit right into the landscape as any rock or any gnarled pine. There are shamans, Taoist wizards flying on clouds, sages seeking the magic herbs and elixirs of immortality, Confucian scholars retiring from the world, and Buddhist hermits seeking enlightenment. One of these, Huiyuan (334-416 C.E.), built a temple at the foot of Mount Lu and went mountain climbing with disciples and lay followers, seeking “cosmic revelation in the mountains.” One would like to know more about this intriguing figure, whose Buddhism, Professor Munakata informs us, is “sometimes called landscape Buddhism.”

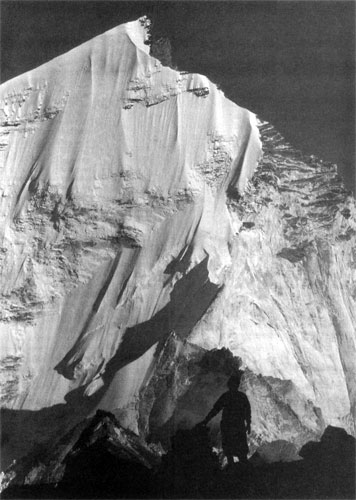

Edwin Bernbaum’s magnificent Sacred Mountains of the World presents a more contemporary approach. Here, the light and color of master mountain photographers reveal mountains hidden within mountains with luminescent clarity. Indeed, the photographers Bernbaum has gathered, including himself, are the modern equivalents of the ancient Chinese landscape painters. But the reader should not stop at the photographs and plates, as wonderful as they are. This is a book that should be read as well as looked at. Bernbaum, author of the highly regarded Way to Shambhala, is an astute student of comparative religion as well as a serious mountain climber and pilgrim. His text is a brilliant and lucid exploration that ranges the world—Mount Sinai, Glastonbury Tor, Kailas, Kilimanjaro, Machu Picchu, Shasta, Mauna Loa, Denali, Uluru, Adam’s Peak, and many more. He gives us all the facts, lore, mythologies, geographies, and people. There is a real danger here of becoming overwhelmed with it all, but happily, Bernbaum also manages to convey a very personal sense:

Something about the smooth slope of the valley caught me up. . . . It suddenly hit me that I was on the edge of Tibet, where there were mountains and valleys that had never been explored.

And suddenly, a feeling that was stronger than a feeling. . . swept through me: the rest of the world is like that, as unmapped and unexplored as Tibet. In some mysterious, inexplicable way, there are valleys and mountains all around us that no one has ever seen or mapped—a world hidden right here, as if in another dimension.

Why do we study, read about, gaze at, contemplate mountains? Because they’re there, right there, under our feet, walking with us.