Jeffrey Hopkins, professor of Tibetan Studies at the University of Virginia and author/translator of twenty-one books, has been practicing Tibetan Buddhism since 1962. His latest manuscript, Sex, Orgasm, and the Mind of Clear Light: The 64 Arts of Gay Male Sex, is a variation of Gendun Chopel’s Tibetan Arts of Love. Hopkins was interviewed for Tricycle in December 1995, in New York City by Mark Epstein, psychotherapist and author of Thoughts Without a Thinker (Basic Books).

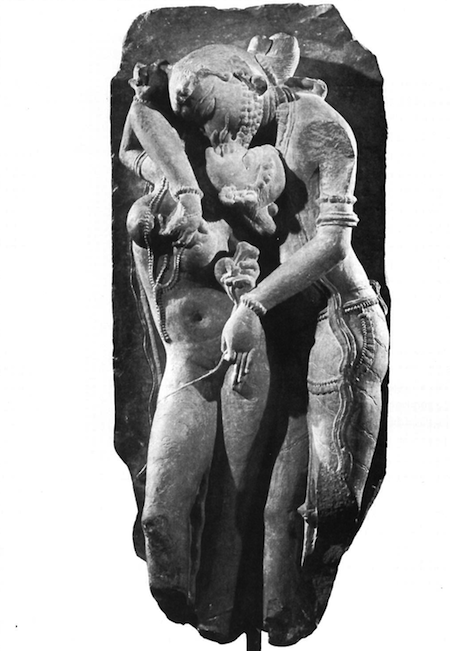

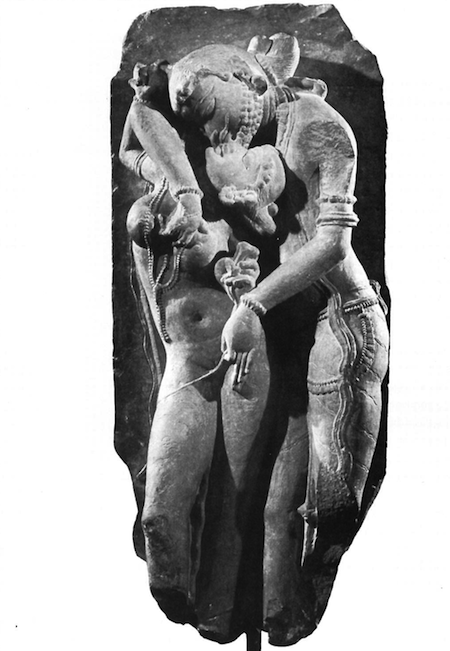

Tricycle: In your article “The Compatibility of Reason and Orgasm in Tibetan Buddhism,” you talk about the physical act of sex as being an opportunity to work in a meditative way with the mind of clear light. In our understanding of Tibetan iconography, of consorts coupling with each other, is it misleading to think of these in terms of being purely symbolic—symbolizing the union of wisdom and compassion? Because now you’re talking about the physical acts of sex.

Hopkins: They do symbolize wisdom and compassion, and also the great bliss consciousness, which realizes emptiness in a nondual way. But one way of inducing this is through orgasm, and thus the pictures are depicting profound practice. It’s very important to me that these images exist on the walls of the temples because it shows that profound realization can be attained right in the midst of sex and that it’s not possible only in some other realm—that this deepest of emotional states has within it the most profound level of consciousness. That’s just wonderful.

Tricycle: There’s a paragraph in Sex, Orgasm and the Mind of Clear Light: The 64 Arts of Gay Male Sex, in a chapter called “Thrill Cries,” where you say, “Given the nature of reality, it is not far-fetched or exaggerated that in the midst of orgasmic bliss one cries out ‘This is it!’ and ‘The ultimate!’” I love that.

Hopkins: Well, you know, it would be absurd to think as you’re going to sleep, “I’m practicing tantra,” just because you’re going to sleep. But it would also be silly to cut yourself off from the possibility of experiencing these deeper states by thinking, “I’m not practicing tantra.” So, in sex, it would be really silly to run around claiming that we—who don’t have that much development of compassion and realization of emptiness and so forth—to claim that somehow we’re practicing tantra, or when we’re angry that we’re being like a wrathful deity. That’s really sick. But sometimes an ordinary person can start paying attention to the entity of the mind in the midst of anger. And that probably can only be done if you don’t have the inflated thinking of, “I’m practicing tantra.” And the same with sex.

Tricycle: Given the fact that so many Tibetan practices require, for example, people of every age and sexual orientation to imagine that they are young, nubile dakinis—as an embodiment of a certain energy—and that so much of Tibetan Buddhism emphasizes the transitory and elastic display of form—why did you find it necessary to retranslate a text with heterosexual imagery into a specifically gay manual?

Hopkins: Why are there heterosexual manuals? Really I did this in order to support one of my own communities—an important one. I felt I would be betraying them if I did not. It might have looked as if I was hiding. I am not.

Tricycle: You’ve been very outspoken, very public about your homosexuality in a way that I think has been very helpful to many people in the dharma by giving the message about being up front and honest and in touch with who one is.

Hopkins: I probably should have realized that I was gay when I was six or seven years old, certainly when I was a teenager. But if in prep school I had said I was gay, I would have been lying to myself. I was so socialized to the opposite. I experimented with heterosexual sex when I came out of the monastery and then went to graduate school and experimented with homosexual sex. But it subsequently took years and years to come out. When I went to teach at the University of Virginia I read in the student newspapers—this was in 1973—that homosexuals were not served beer in the student union. And I thought, “Oh, my. I don’t have a chance.” And I had this self-deception of being bisexual and eventually got married. And there’s no doubt that I used whatever abilities I had in meditation to escape recognizing who I am. So even if the meditation made it inescapable, it also gave me a day-by-day means of escape. Like taking a cold shower.

Tricycle: That’s always my question about meditation: whether it opens you up or gives you another powerful means of defense.

Hopkins: It’s both. And that’s why we need all forms of psychotherapy. The biggest mistake that Buddhists can do is not to take advantage of psychotherapies.

Tricycle: And you came out without any help?

Hopkins: Yes. Almost going nuts, but I decided either I was going to go nuts or come out [laughs].

Tricycle: Has it changed your view of Buddhism in any way?

Hopkins: I don’t think it has. Buddhist practice has been very important for me to realize my own rage at the people who boxed me in. And once that rage is there, to do something with it, to ameliorate it, to realize that this person was a close friend in a former life. And the biggest help has been the awareness that the fundamental mind of clear light can manifest in the midst of the strongest emotional affective state—orgasm.And to see that all other levels of mind, whether confusion, dullness, or all the marvelous things that reason can do are coarser levels of that mind. These are only coarser manifestations of the mind of clear light. This way reason is not arrogantly separated out from this fundamental affective state. When you separate reason out as an autonomous separate entity, then heterosexual men often project their affective side on women and view them as inferior, and they hold the same fear/prejudice against queers because we are so like women.

Tricycle: I was talking to a group of psychoanalysts about this idea of the compatibility of reason and orgasm that you use as the title for your introduction, and their attitude was: what’s the big deal about orgasm? It’s just a return to the vegetative, biological processes. And then I mentioned it to an artist friend of mine who was also aghast who said, “’Compatibility of reason and orgasm’—don’t we even get one tiny moment of orgasm when it doesn’t have to be reasonable?”

Hopkins: That’s right. Here it’s really a compatibility or a continuum so that reason doesn’t get separated off. So you can tell the artist that you do have your moment. And it can be more than a moment. Stretch it out.

Tricycle: When you talk about orgasm in this way, does orgasm mean not ejaculating?

Hopkins: No, I don’t mean it that way.

Tricycle: But I’ve had patients who came in talking about how they wanted to practice tantric sex and the major thrust of what they were doing was trying to prevent their orgasm or deny their need for it.

Hopkins: Yeah, I read about one fellow who was advocating sex without orgasm because orgasm was so awful. I said, “Oh, wow, that’s too bad.” You know the four levels of tantra are associated with four levels of desire and of happiness and bliss. The first one is looking. You know when you see somebody you really like across a room—and it’s wow, and the mind instantly becomes concentrated. To use that mind for something other than just its pleasure, you see—that’s what’s being done. And then the next is smiling, and the next is holding hands or embracing. And the last is union of the two organs, which means orgasm, which on high levels is done without ejaculation. Any of these levels of sexual play is valuable for this practice. It’s not necessary that it just be orgasm.

Tricycle: One of the nicest sections in your text is about the ability to take the sexual, genital pleasure that’s localized and then to stop and move the awareness into the vast sky of mind.

Hopkins: Yeah. It’s sad when people just want to race on toward orgasm.

Jeffrey Hopkins, professor of Tibetan Studies at the University of Virginia and author/translator of twenty-one books, has been practicing Tibetan Buddhism since 1962. His latest manuscript, Sex, Orgasm, and the Mind of Clear Light: The 64 Arts of Gay Male Sex, is a variation of Gendun Chopel’s Tibetan Arts of Love. Hopkins was interviewed for Tricycle in December 1995, in New York City by Mark Epstein, psychotherapist and author of Thoughts Without a Thinker (Basic Books).

Tricycle: In Sex, Orgasm and the Mind of Clear Light, I was struck by the amount of aggression: so much scratching, biting, and sucking was being channeled into the act. I was reading a psychoanalytic text about love relations and what keeps passion alive in couples who have been together for a while. And the theory of this book was that it was the channeling of primitive aggressive and polymorphously perverse sexuality—early infantile sexuality, the channeling of that, unashamedly, in the privacy of the sexual act, that kept passion alive, vibrant in the relationship. And then to see the same thing described in your text—I thought that was a great dovetail.

Hopkins: I suppose my most passionate relationship was with someone who played with the line between pleasure and pain, which means he stayed on the side of pleasure—just near the line of pain [laughs].

Tricycle: You talk about these practices in your book in a very literal, down-to-earth way. Is it necessary, in order to have these experiences, to in fact engage in the physical acts themselves? Or is it possible to do it only through visualization and imagination?

Hopkins: In the practice of tantra, activities with a consort are often done in imagination. And then, under certain circumstances, they are done with an actual consort. Here I’m not necessarily talking about the practice of tantra, but of using ordinary sex as an opportunity to do something that’s like what’s done in tantra. So I would imagine that it could be done in either or both contexts. It’s fun to just imagine and also to see what can be done with another person.

Tricycle: You find that you actually reflect on the texts in your relationships?

Hopkins: Oh, yeah. When I don’t get lost in the process of sex itself I’m trying to pay attention to the mind and to sustain certain visualizations and so forth during sex.

Tricycle: Does that interfere with your experience with your partner?

Hopkins: No [laughs]. I hope it enhances it.

Tricycle: It’s not laying down another layer.

Hopkins: No. I see it as removing several layers of thoughts and opening up possibilities. Because we so often freeze the other person into the one who does this or likes that, or feels this way or that way.

Tricycle: My therapist always used to say true love is always mutual. I noticed in your text you also talked about the feeling of mutuality as essential for the generation of this kind of consciousness.

Hopkins: Yes, although for an extremely highly developed practitioner, the consort can be less qualified, which suggests less mutuality. Although I wonder if there’s still a mutuality that may not be on the level of spiritual realization, but another interpenetration.

Tricycle: Can you talk just a little bit more about the experience of being gay in the dharma? I know you’ve also led a couple of retreats for gay or for gay and lesbian practitioners.

Hopkins: At Zen Mountain Monastery I led a retreat. It was a gay retreat. Other people could come, but the main emphasis was for gay practitioners. And then I co-led another gay and lesbian retreat. Both went well. I think the first one went better than the second one because we weren’t trying to do both the gay and lesbian world in the same weekend. And they’re very different worlds. I’ve heard people say, “Why do gay Buddhists feel that they need to meditate together?” Well, take any group that faces certain socialization problems or faces their own internal situation—why do they ever meet together? It’s because you exchange and feel and gain from other peoples’ experience and knowledge. In the dharma there’s talk about opposites—that night exists in dependence on day, long and short, rich and poor, etc. But there’s a whole group in the middle, too. There’s gray and a whole lot of other colors, and there’s [laughs] the middle class, and the world isn’t composed of twos. I think the idea of opposites is probably a misconception. It’s more like chair and non-chair. Included in non-chair are a zillion different varieties: rugs and walls and lamps and people and you know, you name it. Everything is non-chair. When Tibetan kids learn to debate, one question is about whether a white horse is white. And the answer is no, because horses are sentient beings and sentient beings are not colors. And so this identification with external things is unnecessary. So somebody could turn that back on me and say, “Well, why are you making such a big deal about being gay?” And I’ll say it’s because you make such a big deal about being heterosexual [laughs]!

Tricycle: Many people say that the future of the dharma in the West lies in the realm of relationship, that the preeminence of the monastery is destined to change. You were a monk for a brief time and are now writing explicitly about sexuality. What do you think of this prediction?

Hopkins: I lived somewhat like a monk in Geshe Wangyal’s monastery in New Jersey for five years in the sixties but was never a monk. In any case, I doubt that there has to be sex between two people to have a relationship. Relationships with others are crucial in monasteries and nunneries. I’m a strong advocate of monasteries and nunneries; a level of practice and learning can happen that is hard elsewhere. It’s a preferable way of life for those who have the ability. Looking at my lay friends and their relationships over the last thirty years, I can’t put much hope there. We have to quit expecting nuns and monks to be Buddhas before we will support them. America especially is a tough place for diversity.