As a young Indian prince living nearly three millennia ago, Gotama (Buddha’s original name) enjoyed the finest delicacies available to the warrior caste of that ancient era: sali, a high-quality long-grain rice; dairy products such as ghee (made from cow, goat, or buffalo milk), butter, and curds; meat, especially goat, fowl, venison, and beef; fish and eggs; a variety of fresh and leafy vegetables; and cereal-based beers and liquors.

Despite his comfortable circumstances and rich diet, Gotama was in torment. At the age of twenty-nine, the thought of old age, disease, and death filled him with dread and drained him of his vigor. Determined to solve the puzzle of existence, Gorama renounced his worldly position and set out traveling as a religious pilgrim.

Seekers of the truth in that age refrained from rich food, and Gotama subsisted on roots, fruits, and dry grains. In his intense desire to attain liberation, Gotama eventually assumed the most rigorous diet of the strictest ascetics: one jujube fruit, one sesame seed, and one grain of rice a day. Obviously this miniscule amount of food cannot sustain life, and in fact it was not intended to do so; rather it was a slow form of starvation to purify the flesh and transform the spirit.

Following a week of that meager fare, coupled with his six long years of near abstinence, Gotama’s “eyes were like the reflection of stars at the bottom of a dried-up well, and his limbs like sticks; such was his fast that his spine could have been grasped from the front.” Near death but no closer to his enlightenment, Gotama abandoned his fruitless reliance on asceticism and mental gymnastics. He would, he declared, take nourishing food and either attain awakening or die in the attempt.

What was the dish Gotama took in order to fortify himself for his supreme effort? The earliest texts identify the wonder food as payasa, rice cooked with milk and mixed with crystal sugar and fragrant spices—a kind of delectable rice pudding. The Nidanakatha Jataka gives a colorful account of the preparation of the nutritious dish (known as khir in modern Hindi): a wealthy woman named Sujata, wishing to make a special offering to a sacred tree for granting her a wish for a good husband and a son as her firstborn, pastured a thousand cows in a nearby grove and collected their milk. She fed the milk to five hundred selected cows and then fed their milk to two hundred and fifty cows, and so on in halves until the final product was produced by eight cows. This process greatly enhanced the thickness, sweetness, and strength-giving properties of the milk. This “cream of the cream” was then mixed with the highest-grade rice and boiled. When Sujata discovered Gotama seated near the tree she offered the payasa to him. Gotama ate the rice pudding, his health was restored, and enlightenment attained. Supposedly, the life-giving food sustained the new Buddha for the next seven weeks; during that time “he drank no water, nor did he relieve himself.”

In the palace, Buddha had partaken of the choicest delicacies; as a mendicant, he had to suppress his disgust and eat whatever scraps were put into his bowl. Later, he nearly fasted to death on an ascetic’s tiny ration but then ate rich food to restore his physical and mental vigor. Buddha experienced every type of food sensation—ranging from gustatory delight to revulsion, from satiation to starvation—prior to enlightenment.

The first food Buddha received after his enlightenment was honey and mantha, a cake made from parched barley or curds. These high-energy foods were offered to him by two merchants who found Buddha sitting blissfully under the tree.

Thereafter, food for Buddha was medicine, and he recommended a simple, balanced diet for his followers. He especially praised the ten virtues of yagu, a gruel taken daily as the morning meal.Yagu “gives one life, beauty, comfort, strength, and intelligence, as well as checking hunger, satisfying thirst, regulating the wind, cleansing the bladder, and aiding digestion.” Yagu was usually prepared with a large quantity of water and a handful of rice and salt, but it was also made with sour milk, curds, fruit, and occasionally meat or fish. Even today, a type of yagu known as kayu is a common breakfast in the Far East.

The “Five Foodstuffs” prescribed by Buddha were: (1) curried rice prepared with ghee, meat, fruit, nuts, and so on; (2) baked grain such as barley, wheat, and millet taken in the form of small lumps or as a paste; (3) barley or rice mash mixed with beans; (4) fish; and (5) meat.

It is an indisputable fact that Buddha ate meat himself and that he expressly refused to make vegetarianism compulsory for his disciples (Cullavagga VII, 14). Once Buddha was served food with meat in it by a layman. A Jain ascetic who happened to be present severely criticized Buddha for accepting the meal. Buddha related a story to the Jain monk, in the course of which he explained:

The one who takes the life is at fault, but not the one who eats the flesh; my followers have permission to eat whatever food it is customary to eat in any place or country as long as it is done without gluttony or evil desire.

There is an important stipulation concerning the consumption of meat and fish. One must not have seen the animal killed or had the apprehension that it was killed expressly for him or her. Also, the flesh of elephants, horses, dogs, snakes, lions, hyenas, leopards, tigers, and bears was prohibited. The first two were royal animals, and the rest were considered “unclean beasts.” Buddha also denounced the practice of eating human flesh, a not uncommon ingredient, in those days, of certain medicinal broths.

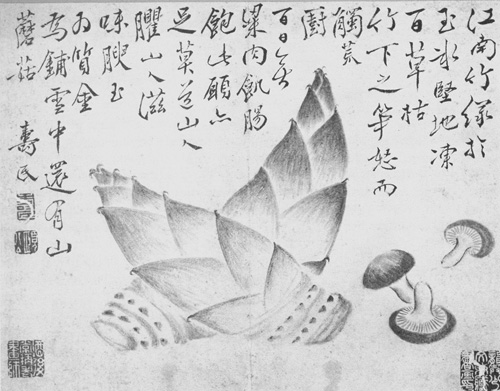

All leafy vegetables were permitted, as well as lotus root, gourds, cucumbers, and eggplant, but garlic and leeks were to be avoided—except in treating certain illnesses—presumably because of their aphrodisiacal powers.

Fruits included in the Buddhist canon include jackfruit, breadfruit, palmyra, banana, coconut, mango, and rose apple. Sweet drinks were recommended by Buddha for their ability to refresh, and he allowed them to be taken in the late afternoon as a kind of pick-me-up. The drinks were made from extracts of mango, rose apple, banana, honey-tree fruit, water lily root, grapes, and sugarcane.

Food was seasoned with salt and spices such as pepper, cumin, myrobalan, ginger, and tumeric. Mustard and cloves were used as flavorings. Molasses (made from sugarcane) was an important sweetener and sweet. Sesame cakes were evidently a great favorite of the monks—one monk was so enamored of the tasty snack that he had to confess his excessive attachment to the treat in front of the entire assembly. Food was cooked in vegetable oil; in case of illness, animal fat (that of bear, fish, alligator, pig, porpoise, or ass) was permitted.

Buddha’s regular fare in his later life consisted of yagu gruel taken with a lump of molasses in the morning, a substantial midday meal of rice and curry, fruit, and vegetables, and in the evening a drink of fruit juice or sugar water. Buddha was convinced that not taking of solid food after noon was the best form of preventive medicine. “Not eating food at night, I enjoy good health, vigor, and comfort.”

The two most important meals of the Buddha’s career were the one taken just before his enlightenment and the one immediately preceding his death. That final meal, served up by a pious but inexperienced cook, has been the subject of scholarly controversy for a century. The following theories of what it consisted of have been put forward: (1) pork; (2) mushrooms; (3) bamboo shoots; (4) rice broth made of dairy products; (5) some type of “elixir.” Whatever the last meal was, and most likely it was a mushroom dish, the significant feature was not the nature of the food but Buddha’s attitude toward it. Buddha clearly recognized that something was wrong with the dish—it might have been spoiled, or made with poisonous mushrooms—but he unhesitatingly accepted the food from the well-meaning but ignorant layman. Buddha ate some and ordered the rest to be buried in a hole, for “only a Buddha could digest it.” As a matter of fact, not even a Buddha could digest that dish because he became violently ill and died shortly thereafter. He was eighty years old.

The point of the story is that Buddha honored the layman by accepting the food even if it was poisonous, and then protected his followers by having the rest of the dish thrown away.

Buddha’s attitude toward food was, not surprisingly, moderate. While encouraging his followers to eat as simply as possible, with grain as the main staple, very few foods were absolutely forbidden. It was the intention, not the food, that was paramount for enlightened eating.

Find other perspectives on food and practice in our special section: Meat: To Eat It or Not.