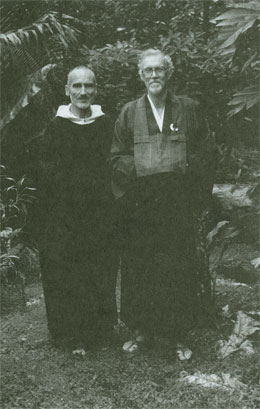

Zen teacher Robert Aitken Roshi and Benedictine monk, Brother David Steindl-Rast, are both prominent participants in the Buddhist-Christian dialogue.

Robert Aitken is the leader of The Diamond Sangha, a Zen community-based in Hawaii with affiliate centers in other countries. Having first encountered Zen in a prisoner-of-war camp in Japan in 1945, he is now, at age 73, considered the dean of American Zen. His books include Taking the Path of Zen and The Mind of Clover.

Brother David Steindl-Rast received a PhD in experimental psychology from the University of Vienna. Although a long-time student of Zen, and worldwide lecturer, most of his time is spent at the Immaculate Heart Hermitage in Big Sur, California.

In January, 1991, these two old friends spent five days together in a secluded retreat cabin on Big Island, Hawaii, sitting in meditation, and discussing a list of questions developed by Brother David, and recorded by attending monk, Brother Kieran O’Malley.

Tricycle asked Dr. Diane Shainberg to extend Brother David and Aitken Roshi’s discussion on authority and exploitation. A psychotherapist living and working in New York City, Dr. Shainberg is the author of Healing in Psychotherapy: The Process of Holistic Change. She supervises therapists and integrates Buddhist teachings into psychotherapeutic models. A seasoned student in both the Zen and Tibetan traditions, Shainberg currently studies with Tilak Fernando, a Sri Lankan Buddhist teacher.

The following excerpt was preceded by a discussion on the tension inherent between egalitarian imperatives and the authority required in order to pass on spiritual teachings. According to the discussion, this tension is not just problematic in North American Buddhist communities that are trying to assimilate Eastern teachings, but exists within Christian communities as well. Brother David then asked Aitken Roshi to say something about the place of authority in spiritual practice:

Robert Aitken Roshi: Someone once suggested that we have a kind of radical retreat at Koko An (our Zen center in Honolulu), with people taking turns being the roshi—the teacher. I think this was a misguided suggestion. Learning in a context of deepest inquiry, where self-deception is most likely to enter in, demands transference and trust. A student might not see the point of a particular idea or act, but if a trusted teacher presents it, the student is able to accept it provisionally and be encouraged to let it sink in.

Someone must hold up the mirror and say, “Look this is what you’re doing, this is what you’re saying.” Or simply say, “no, that can’t be right.” The underlying rationale here is that both teacher and student know what is true, but the student hasn’t quite gotten it yet. But people who have old resentments toward parents and grandparents still lingering in their psyches have difficulties; they are sticking Daddy’s face on the teacher and reacting accordingly. On the other hand, the whole sangha or community is poisoned if the teacher is not true to his or her own teaching and realization, and takes advantage of the transference for selfish reasons.

Brother David: I am very much aware that every one of us wields authority. If you say, “I’m not an authority figure,” be careful to ask yourself for how many people you may be an authority figure after all.

I am asking myself whether our notion of authority today is not dangerously warped. The first meaning of the English word “authority” that you find in a dictionary is something like “power to command.” Wielding power over others is definitely one meaning of authority, but it says something about a civilization in which that has become the first meaning.

The original meaning of authority—and I’m not talking etymologically—is that authority provides, or already is, a firm basis for knowing and acting. We use the term in that sense when we say, “I want to get an authoritative opinion. Should I really have this operation or not?” Then, in that situation we go to a medical authority.

Someone who frequently provides a reliable basis for knowing and acting is put in an authority position: Aunt Emily always knows remedies when you get sick. When you have a cold you go to Aunt Emily. In a village, this role will be played by the elder or the spokesperson or the chief. Everything’s fine as long as the person who is placed in authority truly provides a firm basis for knowing and acting. The problem arises when people no longer provide or justify this trust, but retain the power: then they become authoritarian.

How can you distinguish the authoritarian from the legitimate authority? I struggled with this question for a long time, but the answer became obvious once I had hit upon it: the authoritarian will put you down. That’s the only way in which those who do not belong in a superior position stay there—by putting everybody else down.

The true and legitimate authority builds you up, augments your knowing, augments your ability to act rightly. It raises you up, increases your self-confidence, empowers you. Therefore, the great responsibility of everyone is to question authority. I am talking about a respectful, honest, straightforward questioning of authority. That is our duty, not just our privilege. That’s what keeps authority on the right track. Anybody who has been in an authority position knows how very difficult it is to avoid authoritarian attitudes. How grateful we ought to be to anyone who questions our authority, and thereby helps us stay on the right track!

Aitken Roshi: Of course, along with this come questions of misuse, including the exploitation of students by teachers. This has been a special problem in Buddhist centers—Zen Buddhist centers, Theravada centers, and Tibetan centers—in the United States, over the past twenty years and more. In the past eight years, there has hardly been a center free of scandal. Something has obviously been wrong, something that I could not understand for a long time. Among these newer instances of sexual misconduct, and betrayal of students’ trust, there have been friends and colleagues that I had worked with in the past. One problem was that I honestly couldn’t relate to it personally. It was not something that I had ever been tempted by. Certainly there were women students who were sexually appealing to me, but I just didn’t ever take a first step.

Anyway, that I couldn’t relate to this made me mute, because I could not condemn and separate myself from these friends. At the same time I really couldn’t understand what they were going through. Certainly, I knew they were sexually attracted as I had been, but I couldn’t understand how they could step beyond this. So I, and the Diamond Sangha generally, welcomed refugees from these centers who had been hurt by their experiences with other teachers.

Recently, in an article I published in Blind Donkey, I drew from Buddhist metaphysics and Buddhist experience to establish a ground for trust in the milieu of transference between teachers and students. And I also drew on my observations of my own teachers, who were not only above this kind of sexual betrayal, but also above any kind of betrayal. I can’t think of any important instances where I was let down by any of these four teachers: Senzaki, Nakagawa, Yasutani, and Yamada. Of course the teacher-student relationship is sensitive and sometimes feelings are hurt. “Betrayal” may turn out to be a relatively minor matter of misunderstanding or cross-cultural miscommunication.

The upshot of the article is that good teachers have, by and large, recognized that the sangha is a family and that the teacher has an archetypal place in that family as father or mother, and that sexual betrayal, seduction of a student by a teacher, is incest. So I laid it all out in this article, and I tried to keep myself from being ‘holier than thou’ by acknowledging how difficult it is for me to keep all the precepts. And how, even as I criticize these grave errors in others, I am aware of my own in other respects. My first Zen friend, R.H. Blythe, once said to me, “When I am accused of something that I didn’t do, I bow in acknowledgement of all the things that I did do.”

Brother David: Much of your insight about this matter seems to hinge on the question of incest. I think one ought to ask the question, “What is it that is wrong with incest?” and not assume that it is understood.

Aitken Roshi: I saw an advertisement in a literary journal, presumably entered by a scholar, inviting people who had had positive sexual experiences with their parents or relatives to tell their story. This suggests that out there somewhere is the idea that such experiences can be positive.

Yet it’s not a black and white matter. The deliberate seduction of a woman—taking advantage of her trust—in the milieu of transference is certainly wrong. But we all know happy marriages that began as teacher-student relationships in college, or as psychologist and client. In this case if the dominant one, the psychologist or teacher, finds that his client or his student is someone with whom he wants to spend the rest of his life, then they must dispense with the transference.

Brother David: Not an easy process.

Aitken Roshi: Not an easy process at all. But it has been successfully done. What I am speaking about here, and what all the pain and complaint is about, is the ruthless exploitation, sexually, of clients or students.

Brother David: Exploitation is of course the decisive word. I ask my question about incest, because—and your answer brought that out, too—the decisive thing that makes incest incest is not sexual intimacy between parents and children, but the attitude with which sexual intimacy takes place. I am not talking about full sexual intercourse between parents and children, but judging from what friends of mine have described and shared with me, and from what I know as a psychologist. I am perfectly willing to say that some forms of intimacy between children and parents, which might, to certain people, look incestuous, can be extremely helpful. I would never have brought that up except, first of all, you put so much weight on incest and it’s such an important word in this context, and also because our whole society, in my opinion, is sexually warped. This shows itself not only in sexual aberrations and exploitation, but in the opposite of this particular craziness, in an equally crazy aberration of excessive prudery.

I’m certainly not a supporter of child abuse, but I am by no means a supporter of the media explosion that is going on about child abuse. Do you see what I am talking about?

Aitken Roshi: What we must recognize are the very deep-set archetypes involved in incestuous relations.

Brother David: The parents I am speaking about, have healthy relationships with their children and completely respect this. But our society has become so over-sensitive to any physical intimacy between parents and children that now there are countless grandparents who don’t even want to visit their grandchildren any more. Any caress may be interpreted, by parents or neighbors, as child abuse. They can’t hug or caress the children. They can’t be affectionate and tender and warm. The whole pornographic business has done less harm to our society than this frenzy of prudishness. That’s my deepest conviction.

Aitken Roshi: Of course the parents and grandparents who feel free in a mindful way to be physically intimate with their children are respectful of a certain line that they do not cross.

Brother David: Absolutely. But I’m still interested in how you’re using this incest notion as the lever for an understanding of why sexual relations between student and spiritual teacher are wrong. I would like to suggest that one of the important psychological functions of sexual relations is the testing of the degree of belonging. How deeply do you really belong to me? Sexual advances are subconsciously a means to test that. When mutual belonging is unquestionably given—given on a much deeper or higher level—then the testing on that physical level is inappropriate.

That would be my understanding of why the sexual relationship between parents and children, and between siblings, is totally inappropriate—because the belonging that is tested this way, is far surpassed in the relationship that already exists within the family.

Inside a healthy family, the mutual belonging that can be sexually tested is unquestionably given. To a certain extent, this explains the widespread social rule that one must marry outside one’s clan, and outside one’s village.

That also applies to the student-teacher relationship. Again, the belonging that’s being tested sexually is far surpassed by a belonging that already exists. Incidentally, that’s also a way of understanding why sexual relationships within a celibate community are inappropriate: not because there’s anything wrong with sex, but because testing how closely “you belong to me” is totally inappropriate in this intimate community. We wouldn’t be in such a community unless we belonged to each other in a much deeper sense than can be tested sexually.

Aitken Roshi: What I hear you saying is that sex in its spiritual aspect, and in its very real physical aspect, too, is a unity with the other, and a family member is not an other. The father figure in the person of the psychiatrist or the Zen teacher is not the other. Even the sibling is not the other. And so what we’re doing here is tempering at a very deep level, with the most profound kind of human patterns.

Tricycle asks Dr. Diane Shainberg:

Brother David Steindl-Rast invites us to genuinely inquire, “what is it that is wrong with incest?” The common answer centers around exploitation. Do you know of any instance in which incest can be healing, mutually beneficial, or occur without exploitation?

Diane Shainberg: No. The father is an idealized figure, somebody that the daughter looks up to, whose values and ambitions she can use as a model. There is no possible way that all conventions can be broken, and a daughter still feel supported.

Tricycle: Why did you assume that we were speaking of father and daughter, as if this relationship alone defines incest?

Diane Shainberg: It doesn’t, but more women are in therapy than men. And more women are committed to talking these issues over. Many men have suffered, but the ratio of women to men who go into therapy is probably three to one. So that’s what the therapists hear about. And it’s what Aithen Roshi and Brother David talked about.

Tricycle: Are there examples of teacher-student sexual relationships that have been beneficial for the student?

Diane Shainberg: I’ve never seen anything that I would remotely call a benefit. Nothing. Hypothetically, if a women has already established a sense of connection with her bodily sensations and has been able to honor her own wishes and needs, then maybe it would be a choice. In that situation a person is not seeking a transformational object, or is not looking to make a transformation through a human relationship. But is looking to play, to love, to create, to have fun with a spiritual teacher. But I have never met such a person. Spiritual practice offers a gateway to the interior space. Just sitting and meditating allows people to create some quiet space, and gives them an opportunity once again for healing which consists of the entry into one’s own thinking, sensing, imagining, fantasizing and feeling.

Tricycle: Is it possible that the therapist hears a condensed psychological dynamic that is really no more or less complex, or full of ambivalence than the dynamic with any lover?

Diane Shainberg: Yes, and paradoxically, no. Anyone who comes into the therapist’s office talks with reference to their own experience. For women who have had sexual encounters with a teacher the experiences are of betrayal, confusion, or losing touch with their dreams, feeling that they can’t dare enter into themselves or make sense of what happened.

I have to wonder—I do wonder sometimes for myself—what leads people to spiritual practice. I mean why would they elect that path? And so once you are talking about another possibility of a transformational figure, there is a magical kind of expectation relating to that person. The hope for transformation is so strong in people who have been hurt or who have been overlooked. It’s unlikely that people go into spiritual practice without certain kinds of psychological reasons whatsoever. So I’m not sure that what I’ve seen just happens in the therapist’s office. Spiritual practice is a means—as is anything—to seek what we need in order to heal and also to re-enact the old wounds. How the student re-enacts his or her old wounds with the teacher is where it gets interesting. That’s exactly the same thing as transference. It’s no different. Yet, in the therapy paradigm, those wounds—that dance—is held by the therapist, contained by the therapist, appreciated and observed by the therapist, is allowed for the therapist, whereas in spiritual practice those same re-enactments are taking the place of old wounds, and the teacher is called upon, as I see it, to enable the person to transcend the entire psychological process.

Tricycle: I don’t question your experience as a therapist and I can understand a consistent ethical ‘position’ with regard to student-teacher relationships; but I find it hard to believe that any sexual dynamic is experienced with as much consistency as you suggest, or is so devoid of ambivalence.

Diane Shainberg: It’s hard to see sex outside the realm of one’s personal needs. I don’t know if I would even call that sex. I might call that communion—sexual communion. But the teacher-student sexual cases that we know about do not add up to transcendent experience.

Tricycle: Not one could be described in terms of sexual communion?

Diane Shainberg: Never. In each and every case, the woman was not able to make sense out of it, and once again, was not in touch with her own needs and wants. She had gone toward the figure of authority to validate her, and it had not happened. She was turned into a sexual object and she ultimately felt that she had been abandoned, not only by the authority figure, the spiritual teacher, but by the sangha—the community—and finally, abandoned by herself. Her needs and own wants and thoughts and feelings had been denied by the teacher, denied by the father, denied by herself, so there was no way to turn to herself for nurturance. Women who have had sex with their spiritual teachers have not been able to be at ease inside themselves before the experience and have not been able to be at ease inside themselves after the experience. And that means they can’t go to sleep at night, and that means they can’t dream, and that means they can’t trust other people.

Tricycle: Given the consistency of your experience, on what are you basing even the possibility of sexual communion? What is the source of this idealized version of union?

Diane Shainberg: The evolution of human consciousness. From what we know of our own intimate personal spiritual experience, the rivers of sorrow basically never come to an end. We will never stop breathing, we will never stop being angry. It’s just a question of degree. Eventually we will all have to transcend our own forms of psychological suffering. We can learn how to do that in spiritual practice. So I could say that once I am able to make the transcension, once I am able to accept my grief, my pain, my longings, my confusions, once I am able to accept myself in a psychological way and to know what it is I need and to know what it is I want, and I can be accepting of my inner world, and all of its vicissitudes, then I am ready to go for something called transcension; then I don’t expect myself to recover fully from my grief or my rage or my inner feelings. In other words, we are getting this idea of spiritual communion from people who have met their psychological space and know it intimately and accept it. And those are people who are ready to do the work of transcension. And there are such individuals, I’m not doubting that at all, it’s just that the women we are talking about that I’ve seen have not come to be in that space.