The new edition of the college textbook The Buddhist Religion (Wadsworth Publishing), by Richard Robinson and Willard Johnson (due out this fall), cites. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye as an example of Buddhist influences on modern American literature. P B. Law, a writer living near San Diego, imagines Holden Caulfield’s reaction:

The new edition of the college textbook The Buddhist Religion (Wadsworth Publishing), by Richard Robinson and Willard Johnson (due out this fall), cites. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye as an example of Buddhist influences on modern American literature. P B. Law, a writer living near San Diego, imagines Holden Caulfield’s reaction:

If you really want to know the truth, I wasn’t going to write anything more about all that crazy stuff that happened the week after I got kicked out of Pencey. It was bad enough after D. B.—he’s my brother, in case you don’t remember—talked me into letting them publish the book and all. First off, these crazy literary critics got hold of it and kept talking about what a dumb book it was and what an unoriginal moron I was to say the things I was trying to say. As if, like, you were lying in the street run over by a car and you’d have to be terriibly original about how you were bleeding on the pavement if you wanted these guys to even look at you. That was bad enough.

Then these hot-shot academic types got their hands on it. That was even worse. They kept finding all this deep meaning every time I swore to God or felt under my coat for my secret wound. That was enough to make me swear off writing forever.

But now I’ve found out that some madman has put my name in this stupid textbook on Buddhism, saying that I was some kind of secret Zen master leaving all these suave little clues about koans and satori all over the book, and I dunno, I just couldn’t let it pass. I mean, it’s one thing when literary types write about you, and you let on that you didn’t read it, because nobody expects anybody to read that garbage anyhow. But if somebody says you’re a Zen master and you just keep quiet, it’s like you’re doing some kind of Zen thing and playing along with them. I’ve read a little about these Zen guys and they seem pretty sharp. How would they feel if they heard that some jerk like me was being called a Zen master like them? Old Linchi probably wouldn’t say anything. He was pretty cool, but God, Dogen, I don’t think he’d go for it at all. And, like, even though they wouldn’t say anything, that would make it even worse, if you know what I mean. So I felt I had to stop playing deaf and dumb and set the record straight.

Like that business about the ducks in Central Park. You know, the part where I say,

I was thinking about the lagoon in Central Park, down near Central Park South. I was wondering if it would be frozen over when I got home, and if it was, where did the ducks go. I was wondering where the ducks went when the lagoon got all icy and frozen over. I wondered if some guy came in a truck and took them away to a zoo or something. Or if they just flew away.

I’m lucky, though. I mean I could shoot the old bull to old Spencer and think about those ducks at the same time. It’s funny. You don’t have to think too hard when you talk to a teacher.

They made it out like I’m giving some super subtle little hint here that the duck thing is my own personalkoan, that secretly I’m meditating on it all the time and, like, I’m leaving Pencey because I haven’t yet found anyone worthy to be my true master and all. For Chrissake, you’d think everybody would know that you can have a million things running through your head when you’re shooting the bull with someone like old Spence. But, no, they have to go make me out like some super modest secret meditator. Holden Z. Caulfield, Secret Zenbo. Give me a break.

Then they go on and say I was so obsessed with my koan that I even put it to taxicab drivers, on account of they’re the ones that always seem to know everything about everything. I admit that I sort of brought up the topic with a coupla cab drivers, but jeez, when you’re sitting in a cab you gotta talk about something. You can’t just sit there like some sort of stuckup snob pretending the driver isn’t even a person.

Then they go on and say I was so obsessed with my koan that I even put it to taxicab drivers, on account of they’re the ones that always seem to know everything about everything. I admit that I sort of brought up the topic with a coupla cab drivers, but jeez, when you’re sitting in a cab you gotta talk about something. You can’t just sit there like some sort of stuckup snob pretending the driver isn’t even a person.

That’s the heights of rudeness. And yeah, I was pretty depressed when I got around to checking out the scene at the old lagoon at 3 a.m. in the morning. That’s supposed to stand for the dark night of my Great Death when I’ve hit a dead end with my koan, but who wouldn’t be depressed when you think that you’re going to die of pneumonia and start imagining all the dopey relatives that are going to show up at your funeral?

The problem, though, is that it doesn’t stop with the ducks. They bring up this part, too.

Anyway, I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around—nobody big, I mean—except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the edge of the cliff—I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I’d do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all. I know it’s crazy, but that’s the only thing I’d really like to be.

There’s more, but it’s so depressing I don’t even want to talk about it. All I can say is, don’t believe a word of what those crazy bastards say. If you’re looking for a Secret Zenbo, try old Buddy Glass. He really knows how to chuck that Zen bull around with the best of them. Like inSeymour, An Introduction. The only good part of the whole book—the only part you really care about, I mean—is what Seymour said when his parents were all mad at his kid brother for giving away his new bike to some total stranger. That’s the only thing you really want to know, because it’s so perfect and all, but that’s the one thing old Buddy won’t tell. At first I didn’t understand, because I thought he was just trying to be coy about it, but now I do. Now I understand. If you put something down on paper, even if it’s all perfect just as it is, everybody who reads it thinks that it belongs tothem and they can twist it all up any old way they like.

There’s more, but it’s so depressing I don’t even want to talk about it. All I can say is, don’t believe a word of what those crazy bastards say. If you’re looking for a Secret Zenbo, try old Buddy Glass. He really knows how to chuck that Zen bull around with the best of them. Like inSeymour, An Introduction. The only good part of the whole book—the only part you really care about, I mean—is what Seymour said when his parents were all mad at his kid brother for giving away his new bike to some total stranger. That’s the only thing you really want to know, because it’s so perfect and all, but that’s the one thing old Buddy won’t tell. At first I didn’t understand, because I thought he was just trying to be coy about it, but now I do. Now I understand. If you put something down on paper, even if it’s all perfect just as it is, everybody who reads it thinks that it belongs tothem and they can twist it all up any old way they like.

So I’ve learned my lesson. If you have anything that really means a lot to you, don’t go writing it down. Maybe you can write around it, like, but don’t go writing it down. Nobody I know ever knows enough to leave anything alone.

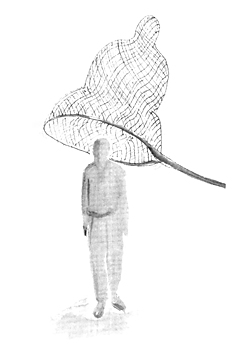

Illustrations by Asha Greer.