In a former life, many aeons ago, the Buddha took up residence in a forest hermitage, living the life of a recluse and studying with a resolute mind. Sauntering through the woods one day, admiring the springtime foliage, he rounded a bend near a mountain crevasse and saw a cave. There at the mouth of the cave, but a few feet from him, lay a starving tigress who had just given birth. This tigress was so overcome by her labors, so weak with hunger, that she could scarcely move. The future Buddha noticed her dark and hollowed eyes. He could see each rib distending her hide. Starved and confused, she was turning on her whelps, on her own tiger pups, seeing them only as meat to satisfy her belly. The pups, not comprehending the danger, were sidling up, pawing for her teats.

The Buddha was overcome by horror—for his own well-being he felt no fear, but seeing another sentient being in distress made him tremble and quake like the Himalaya. He thought to himself, “How futile this round of birth and death! Hopeless the world’s vanity! Right in front of my eyes hunger forces this creature to transgress the laws of kinship and affection. She is about to feed on her own tiger cubs. I cannot permit this, I must get her some food.”

But the next instant he thought, “Why search for meat from some other creature? That can only perpetuate the round of pain and suffering. Here is my own body, meat enough to feed this tigress. Frail, impure, an ungrateful thing—vehicle of suffering—I can make this body a source of nourishment for another! I’d be a fool not to grasp this opportunity. By doing so may I acquire the power to release all creatures from suffering!”

And climbing a high ridge, he cast himself down in front of the tigress. On the verge of slaughtering her pups, hearing the sound, she looked across—seeing the fresh corpse, she bounded over and ate it. Thus she and her cubs were saved.

The Jataka Tales, from which this story comes, gather some of the earliest and strangest writings preserved in the Buddhist heritage. Jataka means “birth.” The old collection, inscribed in a vernacular language called Pali, preserves 550 legends which tell of the Buddha’s miraculous births in the aeons before he became enlightened. The stories occur in a rough-hewn prose, studded with cryptic shards of a much older verse. It is in these broken oddments of poetry that you find something remarkably ancient—animal tales dating in all likelihood to Paleolithic times.

Folklore and archaeology suggest that the Jataka’s interest in wild animal personalities is not an isolated instance. The earliest pictorial art largely depicts animals—think of the Magdalenian cave paintings found in Spain and southern France, or comparable rock art that survives across the planet. There is every reason to believe that the earliest verbal art was concerned with similar themes. As written documents the Jataka Tales are ancient, but from any anthropological perspective they look comparatively recent—humans have been speaking for 40,000 years, perhaps longer. During that time-span the animal fable occurred many places, but survives into our day largely in cultures like India’s, where the old spoken lore met on friendly terms with the scholar’s pen.

I do believe, however, that the Jataka Tales register the first instance in written literature of what I’d call cross-species compassion, or Jataka Mind, an immediate and unqualified empathy shown towards creatures not of one’s own biological species. Perhaps the tales retain traces of a universal contract between living creatures, so long ago vanished that no one remembers its ancient imperatives. With a bow to the old stories, Jataka Mind is that conscious human behavior which bears a whiff of that old way of thinking. Tales like the one just recounted were meant to waken a notion of kinship that sweeps across animal species. Animals in the Jatakas surely justify the storyteller’s interest—they show themselves to be of an equal, often a higher, ethical order than humans.

A thousand, two thousand, maybe ten thousand years after these tales first began to circulate through the villages and pass along the trade routes of Asia, Buddhism cast the Jataka Tales into philosophical form. The Diamond Sutra, a central document in India, Tibet, China and Japan, makes explicit what the old stories had gestured towards. It is here that the Buddha announces an unqualified brother and sisterhood of creatures:

One should produce a thought in this manner: ‘As many beings as there are in the universe of beings, comprehended under the term beings—egg-born, born from a womb, moisture-born, or miraculously born; with or without form; with perception, without perception, and with neither perception nor non-perception—as far as any conceivable form of beings is conceived, all these I must lead out of misery.’

The fundamental vow of the Buddhist practitioner, fashioned two thousand years ago in India, makes explicit the ethical stance. India however, has passed both metaphysics and ethics down the ages in a nearly hallucinogenic cloak of symbols. Myth, folklore, dance, sculpture, music, and painting have made sophisticated doctrine readily available to the popular mind. Thus the finest poem of Buddhist India, which cast its metaphysics into durable shape, was in fact a recasting of the ancient Jataka Tales. In about 400 AD, the poet Aryashura composed his Jataka-Mala.

Mala means garland, sometimes necklace or a string of prayer beads. A Jataka-mala is a garland of birth stories. In polished literary verse, Aryashura recounted thirty-three such tales. They are his versions which stand on the frescos in the Ajanta Caves near Bombay, his versions which adorn the stupa or reliquary at Sanchi. They are also Arya’s versions which appear on the friezes at Borobudur, Java, the most extensive architectural monument the Buddhist world produced.

But Aryashura did not simply retell the old stories, setting them into elegant scholar’s verse—he became possessed by their spirit. What is the Jataka spirit? I don’t exactly know, it is so old. There was a Vedic goddess of forest and wilderness, Aranyani, to whom poets legendary even in Aryashura’s day sang a mysterious hymn. She or one of her sort must have snared Aryashura in the netting of legend, because beyond simply recasting the old stories he invented some of his own, “gathered from the air a live tradition,” in Ezra Pound’s phrase—which is what makes a poet’s work memorable.

Sadly, it is an inability to likewise gather from the air of history such live traditions that has characterized so much Western scholarship in its approach to the legends and lore of Asia. When the approach has not been one of outright condescension, it seems based on a profound mistrust. In London in 1920, the British Sanskritist, A.B. Keith, published a book which is still considered the standard account of Sanskrit literature. Summoning a common attitude towards the art of those cultures which Europe once pillaged and colonized, Keith says about Aryashura’s stories:

Their chief defect to modern taste is the extravagance which refuses to recognize the Aristotelian mean. The very first tale . . . tells of the Bodhisattva who insists on sacrificing his life in order to feed a hungry tigress, whom he finds on the point of devouring the young whom she can no longer feed . . . the other narratives are no less inhuman in the disproportion between the worth of the object sacrificed and that for whose sake the sacrifice is made. But these defects were deemed rather merits by contemporary . . . taste.

Nothing in Keith’s experience, nothing in two thousand years of Occidental scholarship or philosophy, had prepared him for an encounter with this kind of poetry—which is to say this kind of thinking. I can only wonder what he would have said of Mark Dubois, Earth First! activist, who in May 1979 chained himself to a boulder attempting to halt the damming of California’s Stanislaus River. Or what he would have said of Paul Hoover, who in 1985 up in the Middle Santiam squatted on top of a tree he dubbed “Ygdrasil” after the world-tree of Celtic myth, and refused to come down, daring the timber company to fell it. Or what he would have said of Paul Watson who handcuffed himself to a pile of harbor seal pelts, was lifted by a ship’s crane and dunked repeatedly in the Arctic Ocean until his friends rescued him. What would Keith have said, what do dozens of contemporary moralists say today, of the men, women, and children, who are risking their health, lives, bank accounts, and jobs in defense of forests, watersheds, valleys, endangered plant and animal species, every day this year and next?

Buddhists believe that we are all incipient Buddhas, migrating through incalculable reaches of time and space, navigating a complicated succession of births, each of us on course to ultimate Buddhahood. In other words, the stories of the Buddha’s previous births are not somebody else’s but our own. They recount the births and deaths we collectively come upon in our voyage. What we have begun to witness in our day among eco-activists, among radical animal rights workers, among those who draw any line against thoughtless, mechanized, greed-inspired destruction of wildlands, is a resurgence of the old spirit of the Jataka Tales. Makers of story are everywhere being born around us, wakening the old spirit, adding like Aryashura their own tales to the Garland of Birth Stories.

Did I say makers of story? In 1608, the Buddhist historian Taranatha wrote the only known account of Aryashura’s death. The poet, says the story, was walking through a forest glade when he encountered a starving tigress about to devour her own cubs. In one of those enchanted moments, the curtain between literature and life drawing utterly aside, Aryashura offered his own body to stem the tigress’s hunger. The account adds that before Aryashura died he wrote out seventy verses of poetry in his own blood. Sadly, none are preserved in the books that come down to us. Maybe it does not matter. Who would be prepared to read what he wrote?

In India, tellers of story maintain that the epic poem, Ramayana, is the first poem. Its author, Valmiki, holds the title adikavi, “first poet,” which we may take to mean something like “most eminent.” In his poem he gives a compelling account of the origin of poetry, describing how he was one day strolling through the forest, enjoying the springtime splendor of the natural world—the trees, the flowers, creeks, insects, and animals. He pushed his way out to a clearing; as he stood at its margin he saw, in the grass, a pair of krauncha birds, or curlews, mating. The birds were utterly absorbed in their passion, and Valmiki watched transfixed. Suddenly, from the opposite side of the meadow, out of a blind stepped a hunter, a sportsman, who thoughtlessly raised his bow, let fly an arrow, and killed the male krauncha. The female cast herself on the ground next to her fallen mate and let out a terrible cry, beating her wings. Valmiki, aghast at the sight, felt a spontaneous curse wrenched from his throat—

O Sportsman—

having senselessly killed

one of these

passion-gripped krauncha birds—

never the years of your life

will you find a resting place!

Tradition holds this curse to be the first poem. Literalists dismiss the story as fabulous, based as it is on hearsay. But an important truth lurks here: the belief in India that the world’s first poetic stanza emerged in a fit of outrage over the wanton destruction of wildlife.

Poetry to the people of India, whether it crystalizes a mood of compassion, romance, or tranquility, has some intimate, original connection with wildlife and wildlands—and with grief at their unjustified destruction. It is thus no accident that India has also been the place where Hindu and Buddhist thinkers have advanced the concept of ahimsa, “non-injury,” or “non-killing,” which the Buddha made a cornerstone of his teaching, and upon which in the twentieth century the political saint and prophetic environmentalist Mahatma Gandhi founded his activism.

Ahimsa—no wanton killing.

India is also the legendary and not-so-legendary terrain where cross-species empathy gets taken to extremes witnessed nowhere else on the planet. I think of two institutions in particular, the goshala and the pindrajole, both associated with the Jain religion and supported by donations from members of the community. A goshala is a hostel for the care of aged, infirm, and sick bovines, a sanctuary where cattle no longer able to care for themselves, or which have become a burden to family or keeper, live out their lives, sheltered and fed with a modicum of dignity. Goshalas are very much old-age homes for cattle. Lest anyone think this merely confirms some obsession with cattle, I mention the pindrajole, an institution which extends this remarkable sympathy beyond the sacred cow, to all manner of animal, domestic and wild. Several pindrajoles in India specialize in caring for insects.

There are those who regard the taking of any life, wild or other, as unjustified. There are those who extend their notion of cross-species kinship to encompass, not just mammals or birds or fish in isolation, but the larger systems within which individual creatures emerge and vanish in the metabolic weavings of evolution. These systems include forests, rivers, watersheds, mountain ranges, oceans, and cities. I said the appearance in recent years of eco-activists throughout the United States is a resurgence of an ancient contract of kinship. It also suggests a new wakening, perhaps a widening, of what I earlier called Jataka Mind.

Sister movements are emerging, perhaps resurging is a better word, in India. Most exemplary is the Chipko movement which in certain circles has achieved legendary status, by which I don’t mean to imply untrue or fantastic; I mean that accounts of its activities sustain and inspire eco-activists both inside India and well beyond her borders.

The Chipko movement represents the confluence of three streams. There is the old spirit of the Jataka Tales, ever ready to surge up into the folk-life of the Indian people; there is the contemporary scientific understanding of ecosystems and how they operate; and there is that blend of civil disobedience, non-violence, and on-the-table activism which Mahatma Gandhi pioneered.

Thousands of years before Gandhi walked the planet there had been in India a tradition of realpolitik laid forth in old treatises. This tradition, still hanging on after Gandhi’s death, enumerates four time-honored methods of achieving political ends: sowing dissent, negotiation, I bribery, and open assault. These are the expedients of the state. The Chipko movement had other ideas though. “Let your actions set the finer points of your philosophy,” says founding member of Earth First!, Dave Forman, and in keeping with that adage, rather than treating Gandhian environmentalism as a theoretical system, I will try to illustrate the spirit of the Chipko people. This is proper I think, because Chipko has a thoroughly improvisational character—not ritual but experiment, not dogma but story.

Chipko emerged in the Garhwal Himalaya, foothills of the high northern mountains, where in modern times the finest and most extensive forests of India have grown. India: a continent of almost 800 million people with an enormous appetite for wood—for fuel, for fodder, for timber. Almost all this wood has had to come out of the forested Himalayan foothills. The mountain slopes have as a result suffered severe deforestation over the last couple of centuries, leading to the washing away of topsoils, flooding of the plains below, destruction of farmland, wreckage of village and grove by flood and landslide, death of people and livestock—ultimately, the progressive degradation of much of northern India.

One principal problem with the mountain regions was that in the 1960s India and China fought a war over disputed boundary lines. The best way any government has found to stabilize uncertain borderlands is to rapidly develop the area, a course the government of New Delhi pursued. For the forests of the Himalayan foothills, development tipped an already precarious situation. In the late sixties, as the connection between rapid population growth, clearcut timbering and destruction of environmental viability became clear, a number of eco-activists began to speak up in the Himalayan regions, using traditional mountain methods to activate support for a decentralized forest management. They called village assemblies; they went on padayatra, or “pilgrimage by foot” from village to village; they performed folksongs, theater, and dance, dramatizing the connection between large-scale development and collapsing village economies.

In March of 1973, the Simon Company of the distant city of Allahabad was given a contract to cut down a forest of ash trees in the Garhwal. Timber companies had been receiving regular government contracts, but the Simon Company’s seemed particularly gratuitous—the company specialized in sporting goods. Ash lumber is used in our own country for baseball bats, in India for cricket bats. I think there is a direct if unarticulated connection here, looping back to Valmiki’s outrage at seeing a sportsman kill a bird. Anyhow, activists gathered in the village that had traditionally possessed rights to the trees of this forest, and tried to figure out what they could do to stop the clearcutting of their only material resource. Nobody knows how the term first cropped up, one story has an elderly blind folksinger coining it—chipko is a Hindi word that means “hug”—but by meeting’s end the villagers had resolved to go out and hug their trees, putting their own literal bodies between tree and the cutters’ axes.

It worked. The Simon Company and its government lobbyists backed down in the face of widespread publicity.

The following year at the village of Reni, another forest was given out on contract. Many of the local residents were people who had lost tribal territories during the war with China, and when the government and the timber interests discovered that activists planned a tree-hugging campaign at Reni, they utilized some of the age-old political expedients: bribery, negotiation, and sowing dissent. First of all, they told the regional organizer of Chipko, Chandi Prasad Bhatt, that they were ready to include him in forest management policy, and so drew him off to a distant town. They then told the men of Reni village that monetary reimbursement for lands lost during the China-India war would be handed out in another village. All the men, expectably, set out. And busloads of timber cutters slipped in—buses with their windows shuttered. One village girl happened to be out gathering fodder, and saw the buses unload. She rushed back to the village and told Gaura Devi, the local woman of greatest authority, what she had seen.

Gaura Devi quickly rounded up the village women, and they thronged into the forest ahead of the axemen. The laborers, many of whom were drinking, arrived with their axes and found a cluster of women confronting them. They did not know what to make of the situation, but one drunkenly pulled a gun and pointed it at the protesters. Gaura Devi stepped forward, opening her bosom, and said, “The forest is like our Mother. Shoot me instead.” At this, the workers fell apart in shame and confusion. They left their tools, turned around, and began picking their way back along the forest path. The women followed, retrieving the discarded tools and using them to dislodge a concrete walkway that gave passage over an avalanche ravine, cutting off access to the forest. They saved their trees.

In the timeless loop of story, this brings medieval Rajasthan into the garland. It was there that in 1485 the son of a village headman had a vision in which he saw a period of terrific hardship caused by callous human regard for nature. He founded a small sect called the Bishnoi, and laid down twenty-nine tenets which Bishnoi observe to this day. Foremost among the tenets were a prohibition on the cutting of green wood, a prohibition on cremation (which requires prodigious amounts of timber—he instead instituted burial), and a ban on the killing of wild animals. The growth of trees and the flourishing of wildlife in Bishnoi areas caused their village lands to become green, prosperous, good for farmland, good for cattle, while the rest of Rajasthan was becoming desertified.

In 1731, a nearby Maharaja decided to build himself a palace. Needing wood to fuel his lime kilns he sent men to Jalnadi village, about ten miles from present day Jodhpur, to collect wood. When the axemen showed up to cut Bishnoi forest, a woman named Amrita Devi confronted them. She implored them not to cut the trees, but meeting with no sympathy declared the cutters’ axes would have to go through her to reach the trees. She hugged a tree, and as the woodsmen’s axes fell gave out a cry which became a Bishnoi slogan: “A chopped head costs less than a felled tree.”

As Amrita Devi’s body fell into pieces, each of her three daughters immediately and in succession replaced her. After this harrowing incident, the woodsmen retreated for reinforcements, while the local Bishnoi sent out a call to their neighboring villages, eighty-four in all. Of those eighty-four villages, all sent support save a single one which to its eternal shame did not respond. The woodsmen returned to continue their tree-felling, and by day’s end had killed another 359 people. Altogether 294 men and 69 women died. Moreover, the cutters had secured only a third of the timber they’d been charged to collect. When the Maharaja discovered their failure he was livid and hurried to the site to assign responsibility. But seeing the scattered, mutilated bodies, he underwent an instant change of heart and put a blanket ban on tree-cutting in Bishnoi areas.

Today a shrine stands where Amrita Devi fell.

But here, at a point of bewildering excess, one must draw back and acknowledge the emergence of some sensibility which overwhelms any economic, anthropocentric concern for the environment—some utterly mythic realm, underlying the ecological webwork, has declared itself. “The forest is like our Mother,” insisted Gaura Devi. Similarly, Mahayana Buddhism charges one to regard every creature possessing a nervous system, however rudimentary, as “motherlike.” The texts speak of “motherlike sentient beings.” In the beginningless round of birth and rebirth, say the intricate commentaries, in the perennially growing garland of Jatakas, every incarnate creature has at some point been one’s own mother. This vision, as urgent in today’s world as it is tender, is also an expression of how lonely we as human beings will feel the day there are no more spotted owls, no more ivory-tusked mammals, no whales, no clean beaches, no old-growth forests.

So close to our actual future, this loneliness—and many have begun to suffer it grievously—is the resurgence of Jataka Mind.

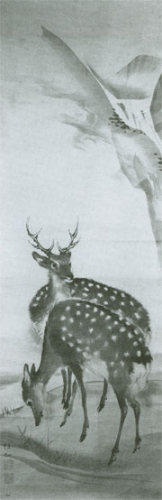

A moment ago I touched on India’s tradition of realpolitik, which advocates four calculated responses to crisis. Four stratagems calibrated to the immediate demands of the state. But beyond these methods a diversity of non-cynical, non-selfserving responses manage to persist. They spring from some sensibility that outstrips any short-term consideration of personal benefit. I give one delicate instance, a poem from ancient Maharashtra State. This anonymous poem is about 2000 years old.

Lone buck

in the clearing

nearby doe

eyes him with such

longing

that there

in the trees the hunter

seeing his own girl

lets the bow drop

Something fresh, something here with a profound and unpredictable intelligence, has shyly revealed itself. That intelligence is growing bolder. Worldwide environmental degradation has drawn forth countless responses, non-cynical and non-compromising. India, Brazil, Indonesia, California. There’s protest over clear-cutting of forest, over damming of river, over stripmining of mountains, over “licensed” or state-sanctioned poaching of endangered animal species.

In this country, one manifestation of that intelligence has become nearly endemic. Though the mainstream press and their parent corporations try to depict it as aberrant and criminal, what’s known as monkeywrenching takes place with gathering urgency. The term, taken into our language from Edward Abbey’s book The Monkeywrench Gang, is informal jargon for pre-emptive acts which disable the machinery of destruction. Such as it occurs, monkeywrenching is not organized but gets carried out by a growing number of homo sapiens who, while clinging to the tenets of non-injury, will no longer tolerate the sacrifice of wildlife and wildlands, the biological viability of this planet, to the machinery of corporate greed.

In all these activities—hugging trees, dismantling bulldozers, “liberating” laboratory animals, chasing endangered game species away from the hunter’s gun—I see the same mind that told itself through the Jataka Tales. Between India and North America profound differences exist, without doubt—but Jataka Mind no more restricts itself to a single culture than does environmental degradation or simple human cruelty.

Once the Buddha was born an ibex with splendid black horns that curved gracefully back over his head. He lived like a hermit deep in an unvisited forest, drinking pure water, feeding on greenery and roaming as he pleased. But the king of a nearby domain decided to hunt in this forest and brought with him a noisy entourage. Excited by the chase, the king romped ahead, leaving his soldiers and horses behind.

With his bow, he pursued deer, rabbit, antelope, with unerring accuracy. Entering a glade he spotted the noble ibex. The ibex {led towards a precipitous ravine and leapt gracefully across. No longer hearing hooves behind him, the ibex drew to a halt, craning his neck backwards. There at the edge of the ravine, pacing nervously, was a riderless steed.

“That hunter must have been high in his stirrups, hands drawing his bow and unable to grasp his reins when his horse balked at the edge,” thought the ibex, “and he has been tossed into the depths.” The thought of an injured man filled him with distress and his heart flooded with sympathy. Looking down he saw the king. The king’s armor had protected him from mortal injury, but he was hurt and unable to climb the steep cliff .

“I am not a demon but a resident of this forest,” called the ibex. “I can carry you out if you’ll trust me.” And he dropped with agility down the side of the gorge. At the bottom he bowed and offered his back to the dazed king, who mounted him like a horse—in a few moments the ibex had reunited the king with his charger.

“How can I reward you?” asked the king, shamed that a few moments before he had treated this dignified creature like an object of sport. “You will come with me to my palace—you can live there in comfort and safety. Life in the forest must be harsh—large cats in the brush, human hunters running you down, tormenting insects. I will house you in my palace yards. “

“The forest is my home,” replied the ibex. “If you think I would enjoy life in a palace you are gravely mistaken. Without my solitude, unable to roam the meadows, I’d be miserable.” Looking at the humbled king the ibex added, “If you would like to reward me then grant me a favor—give up hunting for sport. All creatures are alike in their affections, in their fears, in their pleasures and pain. Why should you do to another animal what done to you would bring grief, panic, and violent death?” The king lowered his head.

At this the ibex trotted into a thicket of greenery and in a moment vanished from sight.