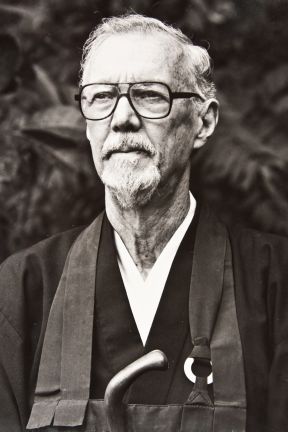

This Aitken Roshi obituary comes our way from the good people at the Honolulu Diamond Sangha, the lay Zen organization that Robert Aitken founded with his wife Anne Hopkins Aitken in 1959.

Robert Aitken Roshi (1917-2010) Aitken Gyoun Roshi, beloved teacher and founder of the Diamond Sangha, died August 5 in Honolulu at the age of 93. Although he had been in declining health for many years and was confined to a wheelchair, he continued to be active, attending weekly zazen at Palolo Zen Center, where he lived his final years, and working virtually to the minute his caregiver drove him to the hospital emergency room. Born Robert Baker Aitken in Philadelphia, he moved to Honolulu at the age of five with his parents and younger brother, when his father, an anthropologist, joined the ethnology field staff of Bishop Museum. After growing up largely in Hawaii (with several intervals in California, living with one set of grandparents or another), at the outbreak of the war in the Pacific he was captured on Guam, where he had been working as a civilian. His amazingly fortuitous introduction to Zen came during his ensuing years of internment in Japan, through a fellow internee, the British writer R.H. Blyth. After his release, Aitken Roshi resumed his interrupted college studies at the University of Hawaii, graduating in 1947 with a bachelor’s degree in English literature. He returned to the university for a master’s in Japanese studies, which he received in 1950, and his thesis, concerning Zen’s influence on the great haiku poet Basho, later became the basis of his first book, A Zen Wave. Between his degrees, he married society-page columnist Mary Laune, and the two of them lived briefly in California, where Roshi started graduate work at the University of California at Los Angeles and began Zen practice with Nyogen Senzaki, a disciple of Shaku Soen Zenji and himself a returnee from internment by the United States. Although he revered Senzaki Sensei and quoted him fondly ever after, this first stretch of practice with him was short lived, and Roshi’s next step, on the advice of D.T. Suzuki, was to go to Japan to practice.

Robert Aitken Roshi (1917-2010) Aitken Gyoun Roshi, beloved teacher and founder of the Diamond Sangha, died August 5 in Honolulu at the age of 93. Although he had been in declining health for many years and was confined to a wheelchair, he continued to be active, attending weekly zazen at Palolo Zen Center, where he lived his final years, and working virtually to the minute his caregiver drove him to the hospital emergency room. Born Robert Baker Aitken in Philadelphia, he moved to Honolulu at the age of five with his parents and younger brother, when his father, an anthropologist, joined the ethnology field staff of Bishop Museum. After growing up largely in Hawaii (with several intervals in California, living with one set of grandparents or another), at the outbreak of the war in the Pacific he was captured on Guam, where he had been working as a civilian. His amazingly fortuitous introduction to Zen came during his ensuing years of internment in Japan, through a fellow internee, the British writer R.H. Blyth. After his release, Aitken Roshi resumed his interrupted college studies at the University of Hawaii, graduating in 1947 with a bachelor’s degree in English literature. He returned to the university for a master’s in Japanese studies, which he received in 1950, and his thesis, concerning Zen’s influence on the great haiku poet Basho, later became the basis of his first book, A Zen Wave. Between his degrees, he married society-page columnist Mary Laune, and the two of them lived briefly in California, where Roshi started graduate work at the University of California at Los Angeles and began Zen practice with Nyogen Senzaki, a disciple of Shaku Soen Zenji and himself a returnee from internment by the United States. Although he revered Senzaki Sensei and quoted him fondly ever after, this first stretch of practice with him was short lived, and Roshi’s next step, on the advice of D.T. Suzuki, was to go to Japan to practice.

His travel to Japan, funded by a fellowship, was nominally for the purpose of pursuing his academic interest in haiku but driven by his fervent desire to deepen his Zen practice. It came at considerable personal expense, carrying him away not only from Mary but also from their infant child, Thomas Laune Aitken, born just months before he departed. Dr. Suzuki referred Bob, as he was then known, to Engaku-ji, the monastery in Kitakamakura where both Suzuki himself and Senzaki Sensei had trained half a century earlier under Shaku Soen. Its abbot at the time, Asahina Sogen Roshi, welcomed this rare American recruit kindly. Ill-prepared for the rigors of his inaugural sesshin, Aitken suffered such painfully swollen knees that afterward he took refuge from the monastery at the home of Dr. Suzuki and his wife, Beatrice. While recuperating, he hit on the idea of going to Ryutaku-ji, where Senzaki’s close friend, the monk Nakagawa Soen, resided. With Soen’s encouragement, Roshi moved there and took up study under its venerable master, Yamamoto Gempo Roshi, who soon named the astonished Soen to succeed him as abbot. Soen promptly raised eyebrows himself by taking the young U.S. layman as his attendant when he paid the expected round of formal calls upon other Rinzai abbots, including the esteemed Shibayama Zenkei of Nanzen-ji. Aitken Roshi returned home to find his marriage headed for divorce and two years later moved back to Los Angeles, where he found employment in a bookstore and resumed practice with Senzaki Sensei. The mid ’50s was a difficult period for him until he landed a position teaching English at Krishnamurti’s Happy Valley School in rural Ojai, north of Los Angeles. In February, 1957, he married the woman who, as acting head mistress, had hired him the year before—Anne Hopkins, of San Francisco. The Aitkens spent their honeymoon in Japan, where Anne “in spite of myself,” as she later put it, was drawn into Zen practice too, joining her husband and Soen Roshi in a seven-day sesshin with Yasutani Hakuun Roshi. An impassioned Soto priest, Yasutani had founded and was director of the Sanbo Kyodan, a small independent sect blending Soto and Rinzai traditions. The karmic repercussions of this first encounter, though not evident at the time, are still resounding. After another year at Happy Valley School, the Aitkens moved to Honolulu, wanting to be closer to Tom, by then eight. They established first a bookstore and then, in 1959, a Zen group, initially in their living room. Senzaki Sensei had died in 1957, so the Aitkens sought the guidance of Soen Roshi, who endorsed the formation of the new group and served as the founding teacher. Soen named both the temple, Koko An, and the new organization itself, the Diamond Sangha. He also installed an altar figure of Bodhidharma seated in a chair, fulfilling a prediction he had made upon its purchase in 1951, when he had insisted that Aitken buy the unusual figure during the time the two had travelled together visiting Rinzai abbots. Besides visiting regularly to conduct sesshin, Soen Roshi sent long-term advisors to live at Koko An and guide the nascent group—the priest Eido Shimano (1960-64) and the layman Katsuki Sekida (1965-71). These advisors doubled as translators for Soen Roshi during his visits for sesshin and, beginning in 1962, for Yasutani Roshi. Soen Roshi soon turned leadership of the Hawaii group over to Yasutani Roshi, and the Diamond Sangha’s bonds with the Sanbo Kyodan were cemented formally. Yasutani Roshi came annually for sesshin through 1969, when at age 85 he gave up such demanding travel. Aitken Roshi’s day jobs during this period were mainly administrative positions with the East-West Center at the University of Hawaii, though at one point he taught college English. After returning from Japan in 1951, he worked as an organizer in Honolulu community agencies, and after moving home once again in 1958, he maintained steady involvement in organizations dedicated to peace, social justice, and civil rights. He helped to establish both the American Friends Service Committee program in Hawaii and a local office of the American Civil Liberties Union. In 1969, Roshi retired from UH, the Aitkens put Koko An in the hands of its members, and they moved with Mr. Sekida to Maui. There, with support from a handful of Zen students, they created the Maui Zendo, initially a sort of mission to the hippie population inundating the island, morphing by degrees into an ever-more-serious residential Zen training center. Soen Roshi stepped in again to lead sesshin there and at Koko An until 1971, when Yamada Koun Roshi, Yasutani Roshi’s successor as abbot of Sanbo Kyodan, began his own long series of teaching visits. The Diamond Sangha flourished in the 70s, riding the U.S. Zen boom of the day and inspired particularly by Yamada Roshi, who, besides being 21 years younger than Yasutani Roshi, was sufficiently fluent in English to deliver teisho and conduct dokusan without a translator present. The Aitkens intensified their own training by travelling to Japan annually, residing for several months each time near Yamada Roshi’s temple in Kamakura. In 1972, Yamada Roshi sanctioned Bob Aitken, as he was still known, to begin guiding students under his supervision. Two years later, Yamada Roshi authorized Bob—henceforth Aitken Roshi—to teach independently, though it was another decade before all the formalities of Dharma transmission were completed. By the mid-70s, Maui Zendo had outgrown its original site and moved to a much larger property. Major sesshin became more frequent, students started to arrive from such distant points as Australia, and Aitken Roshi himself began traveling to teach and published his first books. A Zen Wave appeared in 1978, with his primer, Taking the Path of Zen, following in 1982. With the Aitkens’ backing, Maui sangha members founded a preschool to serve the indigent community in the temple’s vicinity, launched the nationwide Buddhist Peace Fellowship, and began publishing Kahawai, the first journal to address gender issues explicitly in a Buddhist context. Eventually, demographic changes shifted the sangha’s energy back to Honolulu. The Aitkens moved there themselves in 1983, and later the Maui property was sold to underwrite purchase of land and construction of Palolo Zen Center. An almost entirely volunteer-built project, the Palolo temple was designed to provide housing for the Aitkens as well as offices and a complete facility for residential training. Koko An was ultimately sold, consolidating the Honolulu program and its resources. Meanwhile, groups that Roshi had been visiting elsewhere began to seek formal affiliation, and by the mid ’90s, the Diamond Sangha had mushroomed into an international network. Today it has affiliate groups in Australia, New Zealand, Germany, Argentina, and Chile as well as in a number of states across the U.S. In 1988, Aitken Roshi announced the designation of his first four successors—Augusto Alcalde, Nelson Foster, Fr. Pat Hawk, and John Tarrant. By the time he retired, he had added five to this number: Subhana Barzaghi and Ross Bolleter (authorized jointly with John Tarrant), Jack Duffy, Rolf Drosten, and Joseph Bobrow. He recognized Danan Henry as a Diamond Sangha master as well, Sr. Pia Gyger as an associate master, and two apprentice teachers, Marian Morgan and Donald Stoddard. Aitken Roshi continued to teach after Anne Aitken’s death in 1995 but at the end of 1996 retired to Kaimu, on the island of Hawaii, to live near his son. From there, he continued his work while also increasing his active participation in peace vigils and social justice causes. Teaching responsibilities at Palolo passed to Nelson Foster, who shuttled between Honolulu and his home temple, Ring of Bone Zendo in the Sierra foothills, until 2006, when his own successor, Michael Kieran, of Hawaii, was installed as the teacher at the Palolo temple. Roshi and his son Tom moved back to Honolulu in 2004. Two years later, after trying out various housing arrangements and with his health weakening, Roshi settled in again at the Palolo temple. With the support of the Honolulu sangha and financial assistance from many friends, he lived out his days there productively and comfortably, assisted by a dedicated and loving cadre of Tongan caregivers. Among the principal joys of these late years was becoming grandfather to Tom’s three daughters. In the years after his retirement, Roshi published four additional books—Zen Master Raven, The Morning Star, Vegetable Roots Discourse (with Daniel Kwok), and Miniatures of a Zen Master. A final book, his fourteenth, tentatively titled River of Heaven, was in the works when he died. Most of these titles were originally published by his longtime editor and friend, Jack Shoemaker. Many have also been published in one or more translations. Roshi’s death came peacefully, of pneumonia, just over 24 hours after he had been admitted to the hospital. The outpouring of tributes it touched off are testimony to his work and the spirit in which he did it. The memorial service is to be held at the Palolo Zen Center on August 22. For further information on his life, consult a brief 2003 autobiography on the website of the University of Hawai’i library, whose Special Collections hold his papers: http://libweb.hawaii.edu/libdept/speccoll/aitken/autobiography.html. A colorful account of his Zen background is available in “Willy-Nilly Zen,” an appendix to Taking the Path of Zen. Additional material can also be found at the Honolulu Diamond Sangha website, http://www.diamondsangha.org/, and at Roshi’s blog, http://robertaitken.blogspot.com.