Machu Palaces

Jeanne Larsen

Henry Holt and Company,Inc.:New York,1996

342 pp., $25.00 (hardcover)

In China during the Qing dynasty, when hard-riding warriors from Manchuria ruled the vast lands “between the passes,” Beijing’s new gentry altered the rules of architecture. The Manchu lords built rambling compounds with highly ornamented ritual halls and bedchambers facing onto courtyards perfumed by fruit trees, all hidden from the squalid streets by high walls. Over generations, new structures rose to meet their needs—a summer house set aside for an infant male heir, or a walled garden, evocative of the hilly southland, built to cheer a homesick concubine—until brick and mortar came to embody complex genealogy.

This world of “countless gates and knotted passageways” is the cosmos of Sinologist Jeanne Larser’s Manchu Palaces, a tale of a Chinese girl’s path to enlightenment, populated by bodhisattvas, Confucian spirits, and Taoist guides, and leavened with a dozen auxiliary texts purportedly lifted from obscure historical archives. (Purportedly, since nearly every nonfiction fragment is translated by, commented upon, or in some way mediated by alleged scholars whose names read suspiciously like anagrams of the author’s own.) According to Larsen’s ingenious blueprints, one palace courtyard—one story—flows into the next through a web of narrow lanes making for a playful, if somewhat precious, novel.

At the Beijing compound of an Imperial courtier during the reign of the Qianlong emperor (1711-1799), Lotus, an adolescent girl, learns that her position in a family without male heirs obliges her to forge an advantageous marriage. Her girlhood cut short, she dutifully submits to lessons in painting and learns to coax enchanting melodies from the silk-stringed chyn—a seductive skill that will soon serve her well when she wins a commission as a Forbidden City maidservant.

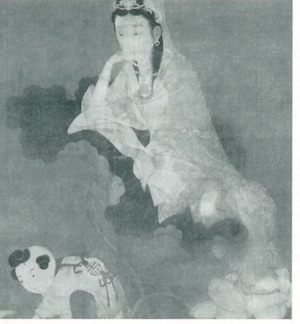

In another palace, this one in the underworld, Lotus’s future is simultaneously plotted in rather different terms. Cassia, her recently deceased mother, begs a richer fate for her only child than servitude at the treacherous palace. Throwing herself at the mercy of a ferociously sarcastic spirit magistrate, the Lord of Mount Tai, Cassia manages to strike a deal. Peering into the terrestrial realm, the magistrate sees that Lotus has misplaced a prized bronze image of a round-breasted White Tara that once belonged to Cassia. If Lotus can find the missing Tara, and the thirty-six companion statues with which it once formed a beautiful mandala, then Cassia can be reborn in to a new human life. Naturally, Lotus’s spiritual journey has its own rewards—and harks to many antecedents in east Asian literature.

In another palace, this one in the underworld, Lotus’s future is simultaneously plotted in rather different terms. Cassia, her recently deceased mother, begs a richer fate for her only child than servitude at the treacherous palace. Throwing herself at the mercy of a ferociously sarcastic spirit magistrate, the Lord of Mount Tai, Cassia manages to strike a deal. Peering into the terrestrial realm, the magistrate sees that Lotus has misplaced a prized bronze image of a round-breasted White Tara that once belonged to Cassia. If Lotus can find the missing Tara, and the thirty-six companion statues with which it once formed a beautiful mandala, then Cassia can be reborn in to a new human life. Naturally, Lotus’s spiritual journey has its own rewards—and harks to many antecedents in east Asian literature.

That, at least, is one of the stories of Manchu Palaces. As Lotus is initiated into various obscure court rituals, such as the annual feeding of the emperor’s silkworms, she

Larsen winds the thread of Lotus’s tale through the letters of a Norwegian aviatrix, the ramblings of a jailed Jesuit missionary, and a note, in her own voice, on the yeasty, sweat-stained silk shoes of a noblewoman with bound “golden lily” feet. The problem with Manchu Palaces is also one of its strengths: we can’t always tell whether Larsen is teaching a history lesson or feeding us veiled information crucial to Lotus’s realization. We aren’t bothered much, since the journey is so exquisite, except when the author affects the jargon of a post-structuralist pedant. In the end, there’s not much suspense surrounding the conclusion of Lotus’s mandala-journey on the mist-enveloped slopes of China’s Five Crest Mountains—the way is, after all, the destination.