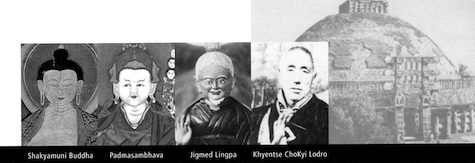

Photo of Jigmed Lingpa courtesy Matthieu Richard.

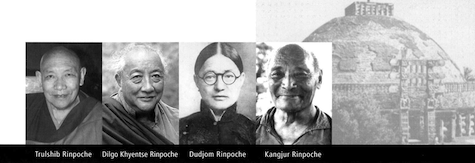

Photo of Trulshib Rinpoche courtesy Vivian Kurtz.

Photos of Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche and Kangjur Rinpoce courtesy Matthieu Richard.

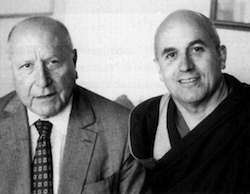

Jean-Francois Revel is one of France’s most prominent public intellectuals. A philosopher and journalist, he has written twenty-seven books. He is a member of the Academie Francaise and a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. Matthieu Ricard holds a doctorate in molecular biology from the Institut Pasteur, Paris. A monk, photographer, and translator, he has lived in the Himalayas for twenty-five years and now resides at Shechen Monastery in Nepal. This dialogue is adapted forTricycle from The Monk & the Philosopher, just released from Shocken Books.

Revel: Is Buddhism a religion or a philosophy? You’ve mentioned the first contact you had with the teacher who made such an enormous impression on you without even speaking. In view of that first experience, are we talking about a conversion in the religious sense, or about some sort of purely philosophical breakthrough?

Ricard: It’s hard to describe such a meeting. What gave it all its value was that it was nothing to do with abstract speculation; it was a direct experience, something I could see with my own eyes, and that was worth more than a thousand descriptions.

Revel: Buddhism has a very positive image in the West. It’s always been seen as a straightforward doctrine, capable of being accepted by a critical and rational Western mind and adding to it a moral and spiritual dimension; a tradition of wisdom not incompatible with criteria that have been developed in the West since the Enlightenment, along with the modern scientific spirit. But when you come to Asia, that ethereal vision of Buddhism is put to the severest of tests. Someone like me is shocked by many aspects that I can only qualify as superstitious. Prayer-flags, belief in reincarnation. . . .

Ricard: The core teachings of Buddhism are not exotic, nor are they influenced by cultural factors of the sort that caused you such surprise. They simply analyze the mechanisms of happiness and suffering. Where does suffering come from? What are its causes? How can it be remedied?

Revel: What do you call suffering?

Ricard: At the initial level of investigation, Buddhism concludes that suffering is born from all the states of mind that plunge it into confusion and insecurity. These negative emotions, in turn, arise from the [false] notion of a self, a “me” that we cherish and want to protect at all costs.

Revel: That part of the analysis is common to numerous Western philosophies. In France, it crops up again in Montaigne and then in Pascal. I myself feel that what’s attracted certain Western philosophers in Buddhism is the idea of being able to attain a kind of serenity, what some psychological schools call “ataraxia.” Ataraxia is an imperturbable state that the wise man has to attain, according to Stoicism; it’s to no longer be exposed to the unpredictable effects of the good and bad that come up in daily life.

Ricard: The practitioner’s mind is likened to a mountain that the winds can’t shake; he’s neither tormented by the difficulties he may come across nor elated by his successes. But that equanimity is neither apathy nor indifference. It’s accompanied by inner jubilation, and by an openness of mind expressed as unfailing altruism.

Revel: You could easily be describing the Stoic sage. But the attraction of Buddhism seems to go a bit beyond this treasure shared by all wisdoms, to a fusion of the self in some sort of undetermined state.

Ricard: It’s not at all a matter of a fusion of the self, but of recognizing that the self has no true existence and that’s the source of all your problems. The very root of all negative emotions is the perception we have of ourselves as an “I” that is an entity existing in itself. But if this self really exists, where is it? In our bodies? In our hearts? In our brains?

Revel: Descartes traced its localization to the pineal gland. Isn’t that rather a puerile question?

Ricard: That’s why the next step is to ask yourself if the self is somewhere in your mind, in the stream of your consciousness. This entity we call “me” must have some definite characteristics. But it has neither color, nor form, nor localization. The more you look for it, the less you can find anything. So finally the self seems to be no more than a label attached to an apparent continuity. To discover as a direct experience, through analysis and especially through contemplation, that the self has no true existence is a highly liberating process.

Revel: Let’s go back, then, to the inconsistencies between Buddhism’s purely philosophical aspects and the superstitious beliefs associated with it in practice. The day before yesterday, for example, we saw a three-year-old child being presented in your monastery in Kathmandu who’s been recognized as the reincarnation of your late teacher, Khyentse Rinpoche. What was the process by which it was decided that the Rinpoche has reincarnated in that child?

Ricard: Buddhism speaks of successive states of existence. We’ve experienced other states before our birth in this lifetime, and we’ll experience others after death. This, of course, leads to a fundamental question: is there a nonmaterial consciousness distinct from the body? Moreover, since Buddhism denies the existence of any individual self capable of transmigrating from one existence to another, one might well wonder what it could be that links those successive states of existence together.

Revel: That’s pretty hard to understand.

Ricard: It’s seen as a stream of consciousness that continues to flow without there being any autonomous entity running through it.

Revel: A series of reincarnations without any definite entity that reincarnates?

Ricard: It could be likened to a river without a boat descending along its course, or to a lamp flame that lights a second lamp, which in turn lights a third lamp, and so on; the flame at the end of the process is neither the same flame as at the outset, nor a completely different one.

Revel: What I find hard to take is this notion of an impersonal river, flowing from one individual to another, and that the goal of Buddhist practice is to dissolve the self in nirvana. Under such conditions, how could it possibly be announced that some particular individual—meaning someone with a high degree of personal specificity—has reincarnated in some other particular individual?

Ricard: The fact that there’s no boat floating down the river doesn’t prevent the water from being full of mud, polluted by a paper factory, or clean and clear. The state of the river at any given moment is the result of its history. In the same way, an individual stream of consciousness is loaded with all the traces left on it by positive and negative thoughts, as well as by actions and words arising from those thoughts.

Revel: But how can particular streams of consciousness be identified?

Ricard: It’s conceivable that a river could be recognized a hundred kilometers downstream from an initial sampling point by analyzing the sediment of mineral and vegetable matter carried in it. In the same way, someone who has the ability to perceive beings’ streams of consciousness directly could recognize the characteristics of a particular stream of consciousness.

Revel: We know there are people who are exceptionally gifted intellectually. We also know that those gifts will yield nothing unless cultivated by intensive training and daily practice.

Ricard: I’d apply the same reasoning, but in terms of contemplative science, not just of I.Q. For the last two centuries, the West has taken very little interest in contemplative science. I was struck by something in the writings of William James. He said, “I tried to stop my thoughts for several moments. It’s clearly impossible. They recur immediately.” Such an observation would amuse hundreds of Tibetan hermits who are able to stay for a long time in a state of awareness free from any mental associations.

Revel: William James is the American author who coined the term “stream of consciousness.” And in fact, when you tell me that Buddhist hermits manage to stop the flow of their thoughts, who can prove it? Do we just take them at their word?

Ricard: Why not? It’s not a matter of blocking thoughts, but simply of remaining in a clear state of awareness, in which discursive thoughts naturally calm down.

Revel: What are they replaced by?

Ricard: By a state of sheer consciousness.

Revel: Yes, but does that consciousness have an object?

Ricard: No, it’s a state of pure awareness without any object. It’s possible to experience that awareness directly by letting concepts dissolve as they form, in the empty clarity of the mind. But it’s not enough just to try to stop the flow of thoughts for a few minutes. It requires personal training that may last for years.

Revel: Does Buddhism teach, or doesn’t it, that beings go from one incarnation to another, and that the goal of ultimate happiness is to no longer be reincarnated, to be finally released and dissolve into the impersonal cosmos?

Ricard: The goal isn’t to get out of the world, it’s to no longer be enslaved to it. What’s called samsara, the “vicious circle of the world of existences,” which is maintained by ignorance, is a world of suffering and confusion. We wander endlessly in it, impelled by the force of our actions, called karma. Nothing forces beings to reincarnate in a particular way except the accumulated pattern of their actions.

Revel: We’ve come back to morals, in fact.

Ricard: You can call it morals or ethics, but it’s actually a matter of the very mechanisms of happiness and suffering. At the moment of death, the pattern of all our actions hitherto is what determines the kind of existence we’ll find ourselves in next. The seeds we’ve planted germinate, into flowers or hemlock.

Revel: So there actually is the idea of multiple lives?

Ricard: Actions, once they’ve been carried out, will eventually bring their results and propel us into other states of existence. But each individual can potentially break this vicious circle by purifying the stream of his or her consciousness, attaining enlightenment, and thus being released.

Revel: So do you agree with Alfred Foucher, who says, comparing ideas about life after death in Christians and Buddhists, “For Christians, the hope of salvation and immortality is the hope to survive. In Buddhists, it’s the hope to disappear.”

Ricard: To no longer be born.

Revel: He says “to disappear.”

Ricard: It’s the wrong word—that’s the old idea about Buddhism as nihilistic. What does “disappear” is ignorance, the belief in a self, but as it does so the qualities of enlightenment appear in all their fullness.

According to the Mahayana, or Great Vehicle, to which Tibetan Buddhism belongs, someone who attains the state of Buddhahood resides neither in samsara nor nirvana, both of which are designated as “extremes.” He doesn’t stay in samsara, because he’s free of ignorance and is no longer the plaything of a karma leading him to reincarnate endlessly. Nor does he stay suspended in the peace of nirvana, because of the infinite compassion he conceives for all the beings still suffering. The depth of the Mahayana resides in its views on emptiness, on absolute truth.

The phenomenal world, as we perceive it, belongs to relative truth. The ultimate nature of things belongs to absolute truth. Absolute truth is therefore the realization of emptiness, of nonduality, which can only be understood by contemplative experience and not by analytical thought.

Revel: What do you mean by emptiness? Is it nothingness?

Ricard: Emptiness is neither nothingness nor an empty space distinct from phenomena. It’s the very nature of phenomena. From an absolute point of view, the world doesn’t have any real or concrete existence.

Revel: But the phenomenal aspect is perfectly concrete.

Ricard: The idea of emptiness is to combat the innate tendency we have to reify the self, consciousness, and phenomena. When Buddhism says, “Emptiness is form and form is emptiness,” it’s not that different an idea from the statement that “Matter is energy and energy is matter.” We’re not denying the ordinary perception we have of the world. What we are denying is that the world has intrinsic reality. If atoms aren’t things, as in Heisenberg’s statement, how would a large number of them taken together—visible phenomena—suddenly become things?

Revel: But doesn’t Buddhism teach that the world has no existence of its own because it’s only produced by our perception? Isn’t that what’s called absolute idealism in Western theories of consciousness?

Ricard: There is a school of Buddhism called the “Mind Only,” which says that, in the final analysis, only consciousness exists, and everything else is a projection of consciousness.

Revel: That’s absolute idealism. It’s just like what Berkeley or Hamelin said.

Ricard: What the other schools of Buddhism reply to such a point of view is that the phenomenal world is perceived via the sense organs and is interpreted by the instants of consciousness that apprehend [that] information. So we don’t perceive the world as it really is, we perceive only the images that are reflected in our consciousness.

Revel: That’s Immanuel Kant’s form of idealism, called “transcendental.”

Ricard: An object is seen by a hundred different people like a hundred reflections in a hundred mirrors.

Revel: But is it the same object?

Ricard: It’s the same object, but one perceived in different ways by different beings. Only someone who’s attained enlightenment recognizes the object’s ultimate nature—that it appears, but is devoid of any intrinsic existence. Buddhism’s final position is that of the “Middle Way”: the world isn’t a projection, but it isn’t totally independent of our minds, either—because it makes no sense to speak of a fixed reality independent of any mental process or observer. There’s an interdependence.

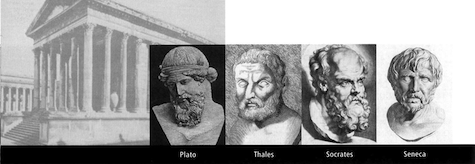

Revel: I’m struck by the number of common points there are, not with this or that Western school of thought as a whole, but with sometimes one phase, sometimes another, of the evolution of Western philosophy from Thales to Kant. We started out with the question whether Buddhism was a religion or a philosophy. For me, the answer’s now quite clear. Buddhism’s more a philosophy than a dogmatic religion. It’s a philosophy with a particularly developed metaphysical dimension, but a metaphysics derived nevertheless from philosophy and not from revelation.