The Good Heart: A Buddhist Perspective on the Teachings of Jesus

His Holiness the Dalai Lama Wisdom Publications: Boston, 1996.

207 pp., $24.00 (hardcover).

In 1994, His Holiness the Dalai Lama took part in the john Main Seminar of the World Community of Religion as a commentator on the Christian Gospels. It was not the first time Buddhists and Christians had come together to discuss the relationship between their scriptures and contemplative practice, but the seminar was unusual in its depth of focus and in its role as a model for bona fide interfaith collaboration. As Robert Kiely put it, “When Scripture is read by someone with a good heart, it comes to life for all of us once again. That good heart, of course, belongs to the Dalai Lama, and The Good Heart, which Kiely edited, is a compelling record of His Holiness’s readings, commentaries, and interactions with others at the seminar.

In 1994, His Holiness the Dalai Lama took part in the john Main Seminar of the World Community of Religion as a commentator on the Christian Gospels. It was not the first time Buddhists and Christians had come together to discuss the relationship between their scriptures and contemplative practice, but the seminar was unusual in its depth of focus and in its role as a model for bona fide interfaith collaboration. As Robert Kiely put it, “When Scripture is read by someone with a good heart, it comes to life for all of us once again. That good heart, of course, belongs to the Dalai Lama, and The Good Heart, which Kiely edited, is a compelling record of His Holiness’s readings, commentaries, and interactions with others at the seminar.

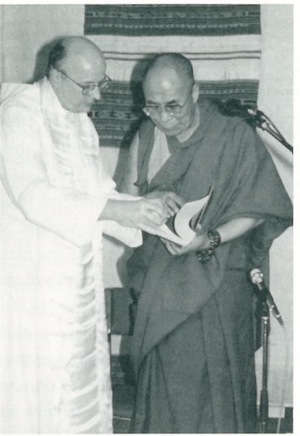

The John Main seminars were instituted in 1984 to honor the life and work of this Irish Benedictine monk (1926-1982), who was first introduced to meditation by an Indian monk in Malaya, where Main served in the British Foreign Service. Main entered religious orders and dedicated his life to recalling other Christians to their heritage of contemplative prayer, especially the traditions of the Desert Fathers of the fourth through sixth centuries. The “Good Heart” seminar was in many respects the natural outgrowth of a 1980 meeting between the Dalai Lama and John Main at an interfaith event in Montreal. The Dalai Lama shared the speaker’s platform with Father Laurence Freeman, a Benedictine monk and former student, friend, and coworker of John Main, and Geshe Thupten Jinpa, the Dalai Lama’s chief translator since 1968 for the subjects of philosophy, science, and religion.

In a spiritual sense, The Good Heart is more highly charged than other recent works on Buddhist Christian dialogue, such as The Ground We Share by Robert Aitken Roshi and Brother David SteindlRast. Aitken and Steindl-Rast’s book records the reflections of two mature and articulate practitioners on their respective contemplative traditions. But because for Christians, Christ lives on through his words in the Gospels, and because for Tibetan Buddhists, the Dalai Lama is the embodiment of Chenrezig, the Bodhisattva of Compassion, there was a heightened religious intensity to this encounter. The Dalai Lama’s attentive reading, for example, of the story of the encounter between Mary Magdalene and the risen Christ brought many of the participants to tears. “It would be hard to say exactly why,” writes Kiely. “Some said later that it was as if they were hearing the words for the first time, as though their tenderness and mystery and beauty had been taken for granted and were brought to life again, like a gift from an unexpected courier.”

The first-century Mediterranean world in which the writings of the Christian New Testament were composed, and in which they became accepted as sacred scripture, was, like ours, a religiously plural one. The Pax Romana had made travel relatively easy, and the Mediterranean became a crossroads for various religions, philosophies, sects, and cults. It is fitting, then, in our fluid world, to find the Gospels once again as a medium of interreligious communication. The Dalai Lama’s comments on these texts reveal deep connections, as well as discontinuities, with the Christian contemplative tradition. With his remarks on the parables of the Kingdom of God, he broaches the distinction between a theistic religion such as Christianity, and the nontheism of Buddhism, revealing a meaningful point of contact between the two:

In the case of Buddhism, one single-pointedly entrusts one’s spiritual well-being to the three objects of refuge, the Three Jewels—Buddha, Dharma and Sangha—as a foundation for practice. In order to have such single-pointed confidence and a sense of entrusting your spiritual well-being, one needs to develop a feeling of closeness and connected ness with those objects of faith. In the case of theistic religions, in which there is a belief that all creatures are created by the same divine force, you have very powerful grounds for developing that sense of connectedness, that sense of intimacy, on which you can ground your single-pointed faith and confidence, that enable you to entrust your spiritual wellbeing to that object.

With this comparison, the Dalai Lama opens up for some disaffected Christians a new way of considering the significance of theism, which may have become for them an outmoded or untenable belief.

A dialogue between the Dalai Lama and Father Laurence reveals deep resonances between the Buddhist and Christian experiences of the ongoing life of their founders within the present-day community.

Buddha Shakyamuni was a historical figure—he existed at a particular time and in a particular space, context, and environment—and his final nirvana at Kushinagar was a historical event. But Buddha’s consciousness and mindstream has continued and is ever-present. Buddha, in the emanation form of a human being, may have ceased; but he is still present in the form known as his sambhogakaya, the state of perfect resourcefulness.

In the Gospel of John (from which the story of Jesus and Mary Magdalene comes), Jesus speaks to his disciples of his continuing presence following his crucifixion, resurrection, and ascension :

I will not leave you orphaned; I am coming to you. In a little while the world will no longer see me, but you will see me; because I live, you will also live. I have said these things to you while I am still with you. But the Advocate, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, will teach you everything, and remind you of all that I have said to you.

The passages discussed by the Dalai Lama include some of the pivotal portions of the Gospels, such as Jesus’ teaching on loving one’s enemies, the Beatitudes, the Transfiguration, the Resurrection and the appearance of Christ to Mary Magdalene. One passage, Jesus’ discussion of his true family, is given a title—”Equanimity”—that would make it unrecognizable to most Christians. It is also unfortunate that the New English Bible, a poetic but somewhat eccentric translation of the biblical texts, was used as the basis to the commentaries. Anyone who chooses to use The Good Heart as a basis for interreligious dialogue should consider using a more reliable translation of the Christian texts.

Another issue for readers is the designation of Father Laurence’s remarks on the Gospel passages as the Christian context. While he manages to convey a wealth of good biblical scholarship and spiritual insight within a few pages, there are times when his stance within a particular tradition of Roman Catholic contemplative Christianity jars. He tends to psychologize certain passages with references to the “ego” or human “defenses,” and downplays the inscrutability or multi-valency of some of the texts, such as in his description of the “pure in heart.” Thupten Jinpa, on the other hand, wisely focuses his “Buddhist Context” on a description of “the Dalai Lama’s own spiritual world, the world of Tibetan Buddhism.”

These weaknesses aside, the book beautifully demonstrates and generates religious dialogue. Besides the core of the book—the Dalai Lama’s readings—the introductory material, conversations among participants, glossaries of Buddhist and Christian terms, and the contextual essays make it a work that would facilitate study by an ecumenical group. The Good Heart not only describes what was said at the conference, but also conveys the context of shared meditation, common meals, and fellowship that made up the experience of the seminar. In this way, it models the elements of a meaningful interfaith dialogue, one that might fulfill the vision shared by the Dalai Lama and John Main at their first meeting. As the Dalai Lama said at the opening of the seminar:

I believe the purpose of all the major religious traditions is not to construct big temples on the outside, but to create temples of goodness and compassion inside, in our hearts….The greater our awareness is regarding the value and effectiveness of other traditions, then the deeper will be our respect and reverence for other religions.

The Good Heart establishes a foundation for just such temples of compassion.