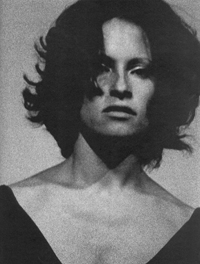

Trudi Jinpu Hirsch is a Zen priest and a chaplain. For many years she was a professional ballet dancer, and she holds the grace of her training in the ease and animation of her movements. Yet there is an inchoate tension to her presence, a feeling of opposites pulling apart or trying to come together, a dancer’s yearning for flight tempered by a sobering gravity. Hirsch’s life, through dance and spiritual practice, has been a struggle to balance these two apparent extremes.

“When I first heard about Zen, I wanted nothing to do with it. For years I’d been practicing meditation four hours a day, and doing intense breath work. I’d read that in Zen you climb the mountain and then return to the marketplace. Forget it. Climb the mountain, yes but then I wanted to keep going to the moon. I wanted transcendence; I wanted out of this painful world. I realize now that life is about relationship and contact, not transcendence, and l owe much of that realization to the work I’ve done in chaplaincy.”

Chaplains are spiritual caretakers who tend to the sick and dying, or anyone in need, and who are placed in hospitals, convalescent homes, hospices, and so on. There are Jewish chaplains, Catholic chaplains, Muslim chaplains, Buddhist chaplains, and then there are just chaplains-those who are trained in the multifaith discipline. Hirsch is a multifaith chaplain working for Healthcare Chaplaincy, a charity organization that is the largest and most comprehensive center for pastoral care, education, and research in the world. Though she offers chaplaincy training for Buddhists through the Healthcare Chaplaincy program, she puts a limit on the amount of training she will give along the singular Buddhist track, encouraging her students to pursue the multifaith program. “Because,” as Hirsch told me, “if you’re attached to your religion, if you don’t have another religion to relate to, you’re never going to know where you’re stuck and where you hesitate to go.

“Chaplaincy comes from the Judeo-Christian tradition; they don’t know it, but they created a wonderful program for Buddhists. It’s so perfectly in line with Buddhism: it’s about being present, about authenticity. I was very excited to be a Buddhist in the chaplaincy program because I can embrace everything. I’m not here to convert anyone. Can I pray a Catholic prayer? sure I can; do I believe in Jesus: sure I do; Moses, Mohammed, yes. I believe all of it or none of it. The work of chaplaincy is to become aurthentic in the moment. This is simple but very difficult. You can deny your teacher and your religion, but you cannot deny the patient looking at you and saying, ‘Why me? Why is this happening? Why is my child dying?’ What are you going to do with those questions? You either stay or leave; it’s that clear,” she told me.

There’s not just one answer to a patient’s vital questions; there is authenticity and sincerity but no static template to use, no religious dogma to rely on. Hirsch makes it clear to her students that doubt (one of the “three pillars” of Zen, along with faith and determination) is not a negative. Perhaps Buddhism’s unique contribution to chaplaincy is its embrace of doubt, of not knowing, of continually questioning the subtlest forms of conditioning, be they cultural or religious.

“Trudi is absolutely uncompromising in treasuring who I am as a human,” said Sarah Nazimova-Baum, a Quaker and former student in Hirsch’s multifaith chaplaincy program. “In the beginning of the chaplaincy training, I felt like a stumbling beginner. I didn’t know what I was doing and it was driving me crazy, and Trudi looked at me with sincere confusion and said, ‘Why would you want to be anything other than a stumbling beginner?’ The work with her was like a slap in the face while simultaneously having your cheeks tenderly and lovingly held.”

Hirsch began to dance at age seven. At seventeen she was accepted into the corps de ballet of the Harkness Ballet Company and traveled extensively in Europe. “It was a fantasy life,” she recalled. At twenty-one, while dancing as a soloist for the Toronto-based Les Grandes Ballets Canadiens, she was selected for a three-month mask-making intensive with the visionary clown guru Richard Pochinko. Hirsch thought the workshop-ritualistically creating various masks connecting to different aspects of one’s personality-would deepen and enrich her understanding of dance.

It did, but those masks allowed her to connect with aspects of herself she had never experienced; they felt simultaneously real and unreal. Her identity expanded,

After a brief stint as a clown on the Capitol steps in Ottawa, Hirsch rejoined her ballet company and struggled unsuccessfully to choreograph the shift in perception she had experienced. In search of a more effective outlet for her creative yearnings, she returned to New York City and began to study sculpture, painting, and drawing at the Art Students League with such luminaries as Jose de Creeft, Marshall Glasier, and Leo Manso. She continued ballet, studying with Madame Darvash. She read voraciously about Eastern religion, meditated with newfound zeal, and took up Iyengar yoga, bur she felt something was missing.

Eventually Hirsch joined an Israeli ballet company called Bat Dor as a principal dancer, and moved to Tel Aviv. On tour in Acapulco, while bodysurfing, she was sucked up by a wave and slammed to the shore. Hirsch nearly drowned. She remembers seeing her life pass before her; someone blew breath into her lungs, but she never found out who it was. She couldn’t move. She remembers fading in and our of consciousness and seeing faces floating around her, like a dream she had had after the mask-making workshop. She’d torn the ligaments on both sides of her neck, and her dancing career was over at the age of twenty-six.

Returning home to her parents’ house in New York to convalesce, she took up painting again at the Art Students League, where she met her future husband, Mark, a fellow painter. They moved in together to a large studio in Yonkers, where they painted and Hirsch meditated four to five hours a day, did breath work and visualizations, and became more and more hermitlike. Mark began to worry and convinced her to do a monthlong artist’s retreat at Zen Mountain Monastery, in Mount Tremper, New York. When she met the abbot, John Daido Loori Roshi (who eventually became her teacher), in a formal private interview (dokusan), he asked what she practiced. When she told him abour the breath work, the visualizations, the meditation, the yoga, he simply replied, “That’s quite a circus.” The statement cut her to the quick. “Somehow he had seen through all of my bullshit, how I was avoiding life, and it pissed me off—but I was hooked.”

Hirsch convinced Mark to move with her to the monastery, where they stayed for the next eleven years, as she became a fully ordained monk. Yet as time passed, she felt less and less at home in the monastery.

“I wasn’t a good monastic. I really tried, and I loved a lot of it—the discipline was familiar to me from my dance background and intense training—but I realized that I needed more freedom to explore intimacy with others and with the world.” When a friend told her about the Healthcare Chaplaincy program, she jumped at it. But it was a difficult decision. She hadn’t finished her training with Daido Roshi and had to sever the relationship, eventually receiving dharma transmission from Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara, abbot of the Village Zendo in New York City, where Hirsch still teaches on occasion. Yet, as Hirsch makes clear, she still loves Daido Roshi very much and readliy acknowledges his influence: “I wouldn’t have become a chaplain without him.”

Hirsch has poured me a cup of tea. On the walls of her apartment are a number of her paintings. They are expressive portraits in explosive color, vibrant like a de Kooning with the luminous intensity of Rothko. They are very good. She tells me she cannot recount her life in a linear fashion, it’s more like liquid with the colors mixing here and there.

“There was one patient I had,” she says. “He was dying. He was an engineer and had a very sharp mind. I really liked him. The day came that he was going to die and he knew it, and he asked me to eat a roast beef sandwich with him, the hell with his special diet. I’m a strict vegetarian, but I said yes, of coutse. He ordered two huge sandwiches. And I remember I was holding mine and he was holding his. When he ate that sandwich, every moment of it was so full. I can do a hundred thousand oryoki meals [Zen’s ritualized meal-taking that encoutages awareness] and as much as I would try, I’d never attain that at-one-ness that he taught me. I ate that roast beef and I didn’t care, vegetarian or not vegetarian. I remember saying to myself, ‘I wish I could be him, the way that he is experiencing life-this is someone who is dying.’ I remember wanting to switch places with him in that moment, because there was no way I was going to eat the roast beef sandwich the way he was eating it. Chaplaincy is like that, one thing after another, just like that.”

“There’s another story I remember,” she tells me. “In the beginning of my chaplaincy training I was called to see an elderly dying woman. I was working the floor at Memorial Sloan-Kettering [the cancer treatment center in New York City} and I went to her room; I’d never met her before. She had tubes down her throat and couldn’t talk. I leaned over to her and said I was the chaplain. She suddenly reached out and grabbed me and pulled me down into her body, staring at me with these intense eyes. I couldn’t get away. I remember feeling like I was being pulled into her dying, pulled down into the depths of her dying. It scared the shit out of me.

“I was locked, eye to eye, face to face with her, and she kept looking at me, holding me. Finally I began to let go, I didn’t fight anymore, and it was like every cell in my body just relaxed, and then suddenly what appeared was this incredible love for this woman. We were still pupil to pupil, yet her expression softened, I softened, we almost did it together. By my allowing death in, I gave her permission to allow death in, or vice versa. I don’t know how to express it better. And she died. It was a fantastic, wonderful lovedeath. There was an amazing beauty to her dying, no flower has ever been as beautiful. In chaplaincy, the patients are your teachers, and this woman taught me to embrace everything, even those places that are terrifying.”