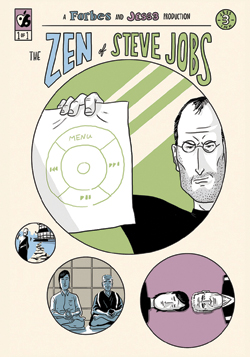

The Zen of Steve Jobs

The Zen of Steve Jobs

Caleb Melby and JESS3 J

John Wiley & Sons, 2012

80 pp.; $19.95 cloth

When Apple cofounder and former CEO Steve Jobs passed away on October 5, 2011, at just 56, the world lost more than a successful entrepreneur and visionary technologist. We also lost perhaps our most famous American Zen Buddhist. Unlike some celebrity practitioners, Jobs was not a very public Buddhist. Despite his wealth and fame, he was not a visible financial contributor to the sangha, and he seldom, if ever, spoke of Buddhism publicly: his celebrated 2005 commencement address at Stanford University made no mention of it. Yet Jobs was a Zen practitioner for his entire adult life, first studying with the Japanese-born master Kobun Chino Otogawa Roshi as a teenager.

It is this lesser known aspect of Jobs’s life that Caleb Melby focuses on in The Zen of Steve Jobs. Melby, a reporter for Forbes Media, teamed up with the Washington, D.C.–based creative interactive agency JESS3 to “reimagine” Jobs’s relationship with Kobun in the unlikely form of a graphic novel. The result is as engaging as it is unexpected.

Melby selects a handful of scenes to populate these pages, concentrating on the years just after Jobs was ousted from Apple in 1985—apparently a time of renewed spiritual discovery for Jobs. From there, the stark monochrome panels jump back and forth across the 30-year friendship of Kobun and Jobs, the nonlinear organization of the book mimicking their “start-and-stop relationship,” as Melby describes it in an afterword.

For example, in his first meeting with Kobun, Jobs is shown as a callow youth, immediately drawn by the earnest young teacher’s iconoclastic reputation. Later, Kobun instructs Jobs—then somewhat older and possibly wiser—in the slow rigors of walking meditation. Finally, in the closing pages, we see a gaunt Jobs in the months before his death, practicing calligraphy—a passion he and Kobun shared—before the narrative jumps back to Kobun’s own final moments. (He died in 2002 at the age of 64.)

Although Melby interviewed some of Kobun’s former students, others of us who knew Kobun may find the book hard to square with our own recollections. Melby’s Kobun is far more talkative—and more fluent—than the one I remember. (“His English was atrocious,” a longtime friend of Kobun’s said in an interview for Walter Isaacson’s recent biography of Jobs.) Melby takes artistic license with many other points as well. For example, the body of water in which Kobun drowned while trying unsuccessfully to save his young daughter is portrayed as a vast and turbulent sea surrounded by remote mountain peaks. In fact, it was a small converted swimming pool on the outskirts of a quaint Swiss resort.

Inevitably, much of the relationship between Kobun and Jobs is left out of this slim volume. Melby readily acknowledges that the book is not a biography: it neglects “people and scenes that any biographer would deem essential.” He doesn’t mention, for example, the fact that Jobs supported Kobun for years, even allowing him to live rent-free in the historic Woodside, California, mansion that Jobs later petitioned unsuccessfully to tear down. Melby also chose to omit one of their “best-documented public interactions,” when Kobun officiated at Jobs’s wedding to Laurene Powell in Yosemite National Park. Yet Melby still captures something of the essence of these two very different men. The vignettes clearly demonstrate the author’s fundamental contention that “Kobun was to Buddhism what Steve was to computers and business: a renegade and maverick,” and he brings Kobun to life as a devoted teacher who, like Jobs, “defied dogma constantly.”

Kobun touched many lives during his decades in the West. He helped Shunryu Suzuku Roshi launch Tassajara Zen Mountain Center in California, the first Zen monastery outside Asia, and eventually led a ragtag sangha scattered across America and Europe. Seeing Kobun in action in these pages, we find it no surprise that as a young man Jobs was fascinated with him and stuck with him over those many years. It’s also easy to see the influence of Zen in much of Jobs’s life, particularly in the radical simplicity he espoused in all aspects of Apple’s industrial design. Melby emphasizes this angle, even suggesting that the circular architecture of Apple’s proposed new Cupertino headquarters had Zen roots. But Melby mostly shies away from the great paradox of Jobs’s life: that despite years of practice he could still be so insensitive and cruel. Stories abound of his fierce temper at work and his casual disloyalty to friends, and something of a Steve Jobs backlash has developed in recent months, with renewed focus on the dismal working conditions at Apple’s suppliers in China. But Melby only hints at this darker side of Jobs, which might otherwise complicate his spiritual narrative beyond the capacities of the comic-book form. Jobs was a regular fixture with Kobun at Haiku Zendo in the early years, and by all accounts was committed to Zen practice. But in the end, Jobs’s commitment was first and foremost to his work, and the amazing products he shepherded into the world may well be the clearest expression we have of his Zen mind.

Kobun himself told a story, not included in Melby’s book, about the young Jobs returning from seven months in India. In those days Jobs was perpetually barefoot and broke, and Kobun would feed him sometimes, even lending Jobs his own tiny sandals so that he could be served in restaurants. One night, Jobs arrived at Kobun’s house after midnight, shoeless as always and dressed in tattered jeans. Kobun’s wife wouldn’t let the scruffy kid in the door, so Kobun and Jobs walked to a small bar in downtown Los Altos.

“I feel I’m enlightened,” Jobs announced. “You look like it,” Kobun agreed. “But enlightened persons have to show their enlightenment with a concrete example, with proof. I need proof.”

A week later, Jobs returned. Smiling, he handed his teacher what looked like a small plate of computer chips. It reminded Kobun of the pachinko pinball machines in his native Japan.

“This is it,” Jobs said, offering the proof of his enlightenment. It was the first Apple computer.