THERE IS A SAYING in Tibet that a beautiful voice can make a wild animal stop dead in its tracks and listen.

Such a voice, and its pacifying potential, are the Tibetan singer Yungchen Lhamo’s karma. A few days after her birth, her mother presented her to a lama who named her “Goddess of Song”. For much of her life, though, singing was just an occasional luxury. Eight years ago, she fled Chinese-occupied Tibet, trekked across the Himalayas, and arrived half-dead in Dharamsala with a single-minded quest: to see his Holiness the Dalai Lama and study the dharma. Today, she has a stunning record, “Tibet, Tibet,” on Peter Gabriel’s Real World label, and a blessing from His Holiness: To fulfill her Bodhisattva Vows, he told her, she must use her voice to help spread some understanding and appreciation of Tibetan culture, as China does its best to stamp it out.

Yungchen Lhamo has followed a tortuous path to rare celebrity—no Tibetan woman has ever recorded on a major label before. Her grandmother taught her folk and religious songs in the high, curling style of eastern Tibet, the family’s homeland. Her family was poor, and when two older brothers died of malnutrition, the five-year-old girl went to work as a domestic servant. By age eleven, she lived and worked in a factory two days’ journey from home. At nineteen, back in Lhasa, a Chinese movie director spotted her walking down the street and cast her in a film called “The First Dharma King of Tibet.”

“That was the first time I realized I could not stay in Tiber, even if I had to leave my family,” she says. “I could see what the film was really showing—a Chinese history of Tibet.”

Yungchen Lhamo stayed four years in Dharamsala, acting and singing in the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts, touring refugee camps in the south of India and twice performing for the Dalai Lama. And she met her husband, Sam Doherty, a Gelugpa practitioner from Australia who had given up his home to be a monk in India.

Neither Yungchen Lhamo nor Doherty had envisioned a life on the international concert circuit—both had hoped for a quieter life in the dharma. But Doherty’s guru gave the couple a mandate: return to the West and work on behalf of the Tibetan people.

After leaving India for her new home in Australia, Yungchen Lhamo went from busking on Sydney street comers to recording dance tracks (a lama intervened and told her to stick to her authentic music), to releasing the record that would prick up the ears of the pop music industry. Now, there are performances at the UN, appearances with His Holiness, rock festivals, recording sessions, press conferences, and meetings with industry suits and celebrities. “Our lives became a mission,” says Doherty, who manages Yungchen Lhamo’s career and translates for her when the conversation goes too quickly. “It’s a difficult life. There’s no permanency in this industry, and a lot of jealousy and backbiting. But that’s a teaching in itself.”

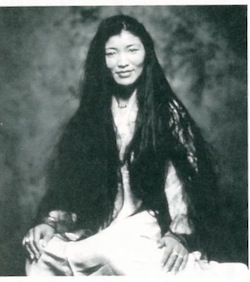

In performance, Yungchen Lhamo is a luminous contrast to the pop music acts she often opens for. Standing rock-still in a traditional Tibetan gown the color of pearls, she sings a capella in a voice that’s clear and sustained as a singing bowl and introduces each song in a quiet, halting English; her smile emanates warmth and unmistakable sadness.

On her album, a sort of musical sutra book of prayers and mantras set to melody, Peter Gabriel laid down cracks of percussion, string, and overtone chanting from the monks of the Drepung Ngakpa Monastery in Delhi. But stylistically, Yungchen Lhamo’s singing actually has very little to do with monastic chanting. Her version of “Om Mane Padme Hung,” the universal mantra of compassion, for instance, is more aria than overtone. “Everyone and every region in Tibet has their own way of reciting mantras,” she says. “Some reel off theirs several hundred times in a low voice. Others have melodies that help the meditative state. That’s where this music comes from. It is meant to be a rain of blessings.”