What’s in it for me?

This is often the first question that lurks behind any new undertaking. But when it comes to spiritual practice—and Buddhist practice in particular—it’s a question bathed in irony. One way to get at this irony is through an expression found in pretty much every Buddhist tradition: seeing things as they are (Sanskrit yatha-bhutam darshanam). To “see things as they are” means, very simply, to see that all samsaric experience is stamped by what are known as the three marks: impermanence (anitya), no-self (anatman), and suffering (duhkha).

The first thing we need to understand is that seeing these “marks” involves shifting attention away from the content of experience and toward its structure. To see things as they are is to unearth our hidden assumptions about ourselves and our world, to bring them into the light of full consciousness, and to notice how, on close inspection, these assumptions often contradict our actual experience.&

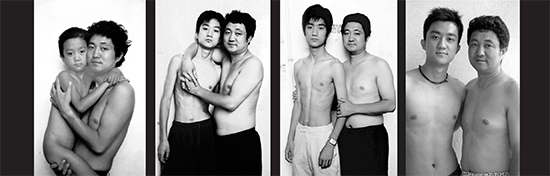

For example, let’s take the first mark: impermanence. Most of the time, change happens slowly enough that we are not fully aware of how everything around us is in a continuous state of flux. Things look stable—that is, they look like well-defined, solid “things”—but the fact is, they’re not. My new shirt looks more or less the same from one day to the next. But what about from one year to the next? And what if we increase the interval to five years or ten? Over such long periods of time it’s quite likely that I’ll notice changes—like wear at the cuffs or collar—that were obviously happening all along, but slowly and below the level of normal perception. The shirt is, in effect, always leaving me, slipping away, though I don’t generally notice. I see only an “object,” a “thing,” rather than a continuous flow of changing events.&

On the other hand, change can happen very quickly as well—I can accidentally tear my sleeve on a nail, for instance—in which case it most often comes as a shock. The same holds true for our relationships with friends and family. We don’t normally notice how people are continually aging, and when on occasion we do it catches us by surprise. I went away to India at the age of 25 and returned at 29. I still remember how startled I was when I first saw my parents again: they had mysteriously turned old. And then, not too many years later, my mother—who was, so far as any of us knew, entirely healthy—went to bed one night and died in her sleep.

Death is, of course, the paradigm of all change. People are dying all around us, but we don’t see it happening; we don’t want to see it, and for the most part we manage to keep it hidden. Back in the 1970s, the writer Ernest Becker won a Pulitzer Prize for his book The Denial of Death, in which he argued that American society is fundamentally committed to not seeing death. And yet, as I discovered while living in India, where dying and death are everywhere in full view, there is a sense of relief that comes from the direct encounter with a universal truth, no matter how unpleasant that truth might be.

Seeing things as they are.

Most of us don’t notice impermanence until it’s shoved in our face. We’re too busy, too focused on having and doing. It’s an unusual person who senses the truth that underlies all our striving.

But at my back I always hear

Time’s wingèd chariot hurrying

near.

Poets notice things the rest of us miss, and they find words to bring what they notice to our attention, to overcome our blindness. Perhaps that’s one reason some of us like reading poetry: it reminds us of fundamental truths we would otherwise miss, and helps us adjust our lives accordingly. In this sense, these lines from Andrew Marvell’s poem “To His Coy Mistress” operate a bit like time-lapse photography. If you had a series of photographs taken at appropriate intervals—of that favorite shirt, for example, or of the people you love—you could visually track an unbroken process that moves from new, to not so new, to old, wrinkled, and worn. Buddhist meditation is designed to accomplish a very similar task. In fact, you can try this very simple exercise, right now:

First, close your eyes and focus your attention on the sensation of breathing. Then, once the attention is more or less settled in, notice how the movement of the breath is no single thing but rather a complex flow of continually changing sensations. Cool air moving in, warm air moving out, a slight tickling at the rim of the nostrils, muscles in the abdomen stretching and contracting as the diaphragm rises and falls. Now direct your attention to the itches, tinglings, and throbbings, the pulsing of the heart, and all the rest of the tiny, constantly fluctuating sensations that together make up the first-person experience of what we call “the body.” Finally, turn your awareness to the arising and passing of thoughts. Notice how, at this very subtle level of experience, ethereal mental objects flit in and out of awareness like fireflies or spirits, appearing and disappearing so quickly and quietly that they can barely be said to exist.

Impermanence means that the appearance of stability we take for granted in everyday life, for practical purposes, is ultimately an illusion, the construction of a mind infused with desire and fear. Behind the facade of language and conceptual thinking there are no stable, well-defined “things” or “people,” only a ceaseless, ungraspable stream of events, like the flow of a river or like waves undulating on the surface of the ocean.

One way to begin to understand the second mark, no-self, is to view it as a particularly intimate encounter with impermanence. To see the lack of self is to notice that there is no stable, unified core to experience. Like all those other people and things out there in the world, I, too, am nothing but a mental construct, a phantom’s mask covering the reality of change.

I grow old. It’s happening all the time, right in front of my eyes, but I don’t notice it because the changes are so gradual. From time to time, though, I’m jolted out of complacency by comparing the face in the mirror to old photographs, or to a memory of an earlier self. But the biggest change of all is the one that I can neither remember nor imagine. No photograph, no image in the mirror, nothing in memory or imagination suffices to conjure up the experience of my own death. It is inconceivable that this “I”—this peculiarly intimate experience of myself as an individual passing through time—could at any moment be snagged on the rough edge of time and ripped apart like the fabric of an old, treasured shirt. Torn beyond repair.

Gesturing toward this second mark of no-self is, then, a way of suggesting that something is seriously amiss in my assumptions about what it is to be a person in a world. My day-to-day perspective makes sense only in some limited fashion, because it fails to take into account the fact that there is nothing about me that isn’t in motion, always already torn and lost.

But no-self is more than a recognition of my own impermanence. It’s also a comment on what philosophers call the problem of “agency.” At the center of our normal experience of self is the conviction that this “I” is an actor who makes things happen. I am an agent; namely, the agent of my own actions, the one who speaks and thinks. The feeling is as if there were a tiny homunculus sitting somewhere in my head, just behind my eyes, perhaps, making decisions and choices, pulling levers and pushing buttons, causing my arms and legs to move, calling words and thoughts into being. It’s a view of the self that we take for granted in everyday life. But does it hold up on closer examination? To not take things for granted is the essence of Buddhist spiritual practice.

Because I have a whole lot invested in this idea that I’m in control of, at the very least, my own body and mind, the mere suggestion that this sense of control might be illusory appears on the face of it to be absurd. Then again, at a certain level it’s completely obvious that if I were in control of my body, I would probably not choose to make it vulnerable to old age, sickness, and death. And if I were in control of my mind, why would I choose to call up worries and regrets? So when it comes right down to it, who is this “I,” this puppet master, presumed to be totally separate from the body and mind that it so effortlessly manipulates? Once again, there is some sort of problem here, some sort of unexamined contradiction in my assumptions. And once again, the preeminent Buddhist tool for unearthing such contradictions is meditation. Try this:

Begin by closing your eyes and focusing your attention on the sensation of breathing. When you’re settled, notice how the sensations come and go spontaneously, how the process of breathing happens all by itself. Fortunately, I don’t need to consciously control my respiration; all of this is managed quite nicely by the autonomic nervous system. The same can be said for the beating of my heart or the digestion of this morning’s breakfast. All these metabolic functions take place on their own, without any intervention on my part. In this respect such “internal” processes are no different from things “out there” in the world, like the wind and rain, or the sound of a car passing outside my window. It all simply happens, without any assistance from me.

Notice, now, how the same is true for thoughts—memories, hopes, expectations, regrets—all of them coming and going on their own. I don’t make them come and go, nor can I make them stop. It’s all simply happening, spontaneously arising and passing away.

To take notice of sensations and thoughts in this way does not mean to think about how they come and go. It means, rather, to open a space of attention, a kind of watching that feels, in experience, separate from what is watched. Drawing a distinction in first-person, direct experience, between “watching” and “thinking,” is a subtle undertaking, primarily because awareness is so easily and habitually conflated with thought; but with continued practice a line can be drawn. Or, to be precise, the line between “inner” and “outer” can be re-drawn in this peculiar way. Like all dividing lines, this new line, too, is ultimately false; but beyond its falseness there are no more words.

As a final exercise, try watching for the decision to open your eyes. Sit quietly, eyes closed, and observe, very carefully. See if you can catch yourself, as we say, making this decision. Or is it that, in direct experience, what we call a “decision” happens all by itself, like any other sensation or thought? After all, I never know in advance what I’m going to decide; I only know what has been decided after the fact. If I look very closely in this way, it’s possible to see that I only imagine I make decisions.

No-self means that the appearance of an unchanging, individual agent who makes things happen is mere appearance, the construction of a mind infused with desire and fear. Behind the facade there is no such self, only the ceaseless, ungraspable stream of events that spontaneously emerge and disappear.

The third mark of all samsaric experience is usually translated as “suffering,” but the truth is that no English word captures the full range of meaning of the Sanskrit word duhkha. Duhkha accompanies every form of physical and mental pain, but duhkha is not, in itself, identical to either physical or mental pain. Duhkha is something else, a far more subtle, all-pervasive dis-ease, a chronic discontent that underlies and infuses our constantly shifting experiences of pain and pleasure. As it happens, the very things that bring us the most happiness in life are themselves causes of duhkha, because they are tenuous, fragile, and ultimately subject to loss. This includes not only material things but also and especially our genuine accomplishments, the successes that bring us recognition and social status. And, perhaps most significantly, the company of people we love brings us duhkha, because we know full well that each one of them may, one way or another, leave us at any time.

Seeing things as they are.

This is not something I want to think about. And precisely for that reason, I find ways to not think about it: by staying busy with purposeful work, by immersing myself in entertainment and social games, and, ultimately, through the uniquely human capacity of denial. But denial, as Freud pointed out, exacts a psychological toll. It comes at the price of an all-pervasive anxiety that infects everything, making it impossible for us to experience any genuine happiness in life. This is the meaning of duhkha.

Let’s be clear: Duhkha is not a suffering experienced by the personality; duhkha just is the personality. To be somebody—anybody—is to continually suffer.

To penetrate the accumulated layers of denial and consciously connect with this level of continual suffering is not easy. It’s like breaking an addiction. The first difficult obstacle is that I resist thinking of life, especially my own life, in these terms. I don’t want to think of my constant search for happiness as a kind of addiction, a form of suffering. I don’t want to think about how my sense of control may ultimately be an illusion, how any identification whatsoever with the elements of my individual self and its world, which includes everything subsumed under the heading of “personality,” entails suffering. I don’t want to seriously contemplate the possibility that underneath all my pleasures the dark current of duhkha flows like a subterranean river, polluting everything with the stench of an insatiable hunger and fear I cannot afford to acknowledge because it would make my present life intolerable.

Nevertheless, to see this third mark, also known as the first noble truth, is to see things “as they are.” Seeing this fact about our experience is the essence of Buddhist wisdom. Here it is, finally, that we are given a definitive answer to the question with which this essay began: What’s in it for me is always nothing but continued suffering and loss. Clearly, this is not a message I want to receive.

The consequences of this insight for our understanding of Buddhism are enormous, beginning with its implications for how we conceptualize the goal of Buddhist spiritual practice: given the nature of wisdom, nirvana—or “enlightenment”—cannot mean the end of my suffering.

All of this is explicitly worked out in the Mahayana. Perhaps the most celebrated example of Mahayana teachings on this subject is the parable of the burning house, found in the Lotus Sutra. In order to coax the children out of their burning home, the wise father promises to give them whatever toy they most desire. Motivated by this promise, “pushing and shoving each other in order to be first out,” they manage to escape alive. What they receive, however, is something altogether unexpected, a new kind of teaching that utterly transcends any appeal to self-interest. They learn that all forms of desire for self-centered happiness are a dead end, that wisdom (prajna) and love (karuna) are ultimately no different. For a bodhisattva, love is the living expression of what is seen to be true.

But what could this mean?

Like the translation of duhkha, “love”—my translation of the Sanskrit karuna—does not necessarily imply that we have any real understanding of the original term. The English word love is notoriously ambiguous. And yet, despite the semantic ambiguities, I prefer this to the more common “compassion,” which is, in my view, too guarded. Too safe. Compassion seems to me to imply a sort of protective distance between myself and others. When I say to my wife or child, I love you, what I’m expressing is more complex and intimate than a simple feeling of compassion. Still, we have to ask what “love” might mean in the context of Buddhist practice. How is it wise to love?

To explore this question, I want to turn to what may appear, at first glance, an unlikely source for help in understanding the nuances of the Buddhist spiritual path. The following words are spoken by Krishna, a character in my novel, Maya. He is defending the Hindu practice of arranged marriage to Stanley Harrington, a young American scholar freshly arrived in India. “Outside of marriage,” Krishna explains,

. . . there is only passion, and passion is not to be mistaken for love. Love is built on commitment to one’s dharma—one’s sacred duty—and not on personal desire. One’s dharma is much greater than the personal desires of a man and a woman. The circumstances of life determine to whom we must surrender.” His eyes dropped for a moment; his voice softened. “But the person to whom we surrender is only of secondary importance, for in truth, we are surrendering to our dharma.”

When Stanley expresses skepticism about the idea of committing to lifelong marriage with a partner selected by one’s parents, Krishna replies, “It may fail—one may fail to fulfill one’s dharma—but there is no other path to love. There is no mystery, Mr. Stanley. Love is not about getting what we want. Love is about how we live with what we are given.”

On hearing this response, Stanley, whose marriage has recently collapsed as the result of his own infidelity, comments wryly: “This was not the sort of thing I wanted to hear.”

For orthodox Hindus, marriage has traditionally been understood as a form of spiritual practice, and like all forms of South Asian spiritual practice, the institution of arranged marriage is grounded in the ancient Vedic idea of dharma, a Sanskrit word meaning “support” or “basis.” In the Rig Veda, the oldest extant record of Indian religion, the word dharma first occurs in a series of verses describing the self-sacrifice of the Original Being (purusha) that creates and sustains our world. Self-sacrifice is, then, the support of the spiritual life. The etymology of the English word sacrifice embodies a similar idea: the word is made from two Latin words meaning “to make sacred” (sacer facere). Like every other Indian teacher of his time, the Buddha insisted that he, too, was giving voice to the dharma. He was merely finding a new idiom for an ageless, universal law of self-sacrifice. He was doing what poets do: reminding us of a fundamental truth we might otherwise miss and helping us adjust our lives accordingly.

There’s a lot one can learn from seeking to place the Buddha’s teaching in the wider historical and social context out of which it arose. In this case, by tracing the chain of associations that connects the orthodox Hindu practice of arranged marriage with the Buddhist path to awakening, we stand to gain a deeper understanding of a particularly subtle and discomfiting aspect of Shakyamuni’s teaching.

Love is not about getting what we want. Love is about how we live with what we are given.

This is the dharma that the Buddha passed along, placing his imprimatur on a primordial truth he had heard from his teachers, but truly learned only through arduous struggle: One way or another, the world will take me from myself, and I will suffer. To see this truth is to see things as they are. But how does one begin to affirm such a truth? How does one begin living with love?

As with any marriage, this new way of living begins with a vow. In Mahayana Buddhism this is the vow (pranidhana) of a bodhisattva, passed down to us in many languages and many forms, all of them acknowledging, in one way or another, that the task of authentic love demands nothing less than absolute, unconditional self-surrender. Love in this sense is akin to death, for it occupies an uncharted realm where language and conceptual thought find no purchase, where memory and imagination must be left behind and all concern with me or mine is ultimately pointless and irrelevant. What does it mean to say, I am dying? Or, I am in love with this troubled world? The first-person pronoun remains, but only as a grammatical marker, a strictly conventional truth that is clearly being pushed beyond its logical capacity to serve.

Of the many versions of the bodhisattva’s vow, perhaps my favorite is this one, chanted every day in Zen monasteries:

Sentient beings are numberless; I vow to save them all.

Desires are inexhaustible; I vow to put an end to them.

The teachings are boundless; I vow to master them.

The Buddha’s way is unattainable; I vow to attain it.