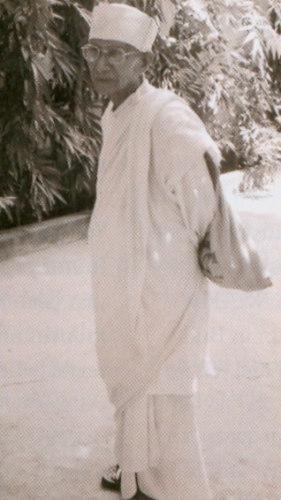

Achariya Anagarika Munindra, affectionately known as “Munindraji,” passed away the morning of October 14, 2003, following a long illness. He was eighty-nine years old. A meditation master and Pali scholar, Munindra introduced many of today’s notable Western teachers to Vipassana practice. Revered for his gentleness, wisdom, and insatiable curiosity, Munindra translated his devotion to Buddhist practice and profound knowledge of the Pali canon into a dharma readily accessible to Westerners.

Munindra was born in Chittagong, Bangladesh, to the Barua family, descendents of the original Buddhists of India forced east by the eleventh-century Muslim invasion. During the 1940s he traveled to India to serve with the Mahabodhi Society of India in Sarnath, an organization devoted to preserving India’s Buddhist history, and in the 1950s he was appointed superintendent of the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya, the site of the Buddha’s enlightenment.

During his initial tenure at Bodh Gaya, Munindra realized that although he was residing at the sacred site, he wasn’t yet putting the Buddha’s teachings into practice. Upon receiving an invitation from Burmese master Mahasi Sayadaw, he traveled to Rangoon to study at the Thathana Yeiktha Meditation Center. He spent nine years under Mahasi Sayadaw’s tutelage, eventually becoming the teacher of Dipa Ma. Munindra then returned to Bodh Gaya and began teaching Vipassana meditation there, as well as throughout India, Europe, and the United States.

Joseph Goldstein, cofounder of the Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts, shares his memories of Munindra:

I met Munindraji in Bodh Gaya in 1967, just a year after he returned from Burma. In those days there were very few people practicing Vipassana in India, and I was one of his first Western students. Although he didn’t have any of the “enlarged” qualities one would expect of an Indian guru (he didn’t immediately strike me as embodying profound peace or great charisma), Munindraji’s deep understanding of the dharma and his total ease with his own eccentricities captivated my interest. Whatever would come up in our lives or in our practice, he would always tell his students, “Be ‘simple’ and ‘easy’ about things.”

One time a few of us were at the bazaar in Bodh Gaya, and he was going from stall to stall, bargaining for a few cents’ worth of peanuts. When we asked him, “Munindraji, why are you getting so caught up in bargaining for a handful of peanuts? We thought you told us to be simple and easy,” he replied, “You need to be simple—not a simpleton.” He also had an enormous curiosity about things. When he visited the States, we took him to the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, and he read the captions on every single exhibit he passed by. After about six hours, we were exhausted! I was lying down on one of the couches, and Munindra was still going—his energy was phenomenal. He moved and spoke very quickly, but he was always in himself, in his body, and just watching him do things was a great teaching.

Munindra also had a tremendous openness of mind to different meditation methods. When he finished his training with Mahasi Sayadaw, he traveled around Burma and studied with about twenty-five different teachers, all teaching different techniques of Vipassana practice. He always said that he felt there was no conflict among any of them. His openness was a striking example of a deeply nonsectarian attitude that would be so helpful in the world today.

I had known that Munindra was ill for much of this past year, and so his death was not unexpected. Still, in the moment of getting the news of his death, it felt like the passing not just of a beloved teacher and a great presence in my life, but of a certain pivotal era in the transmission of Buddhism from East to West.