Abandoning houses, going forth,

Giving up son, livestock, and all that is dear,

Leaving behind desire, anger, and ignorance,

Discarding them all,

Having pulled out craving down to the root,

I have become cool, I am free.—Verses of the nun Sangha (Therigatha 18); trans. K. Norman

There are these fools who doubt

That women too can grasp the truth;

Gotami, show your spiritual power

That they might give up their false views.—The Buddha’s instructions to Mahapajapati (Gotami Theri Apadana 79) trans. Ayya Tathaaloka Bhikkhuni

In the inaugural issue of Tricycle, the editors ran an excerpt from Old Path, White Clouds, a colloquial retelling of the Buddha’s life by Thich Nhat Hanh, about the genesis of the bhikkhuni, or nun, lineage. While the particulars vary from version to version, the story centers on Mahapajapati, the Buddha’s aunt and surrogate mother—and an ardent disciple—who asks the Buddha to admit her to the monastic sangha, but he turns her away.

Dead set on ordaining, she and her following of 500 women cut off their hair, don saffron robes, and walk 150 miles to Vesali, where the Buddha is teaching. Again, she is refused. Moved by the women’s plight, Ananda, the Buddha’s principal attendant, intercedes on Mahapajapati’s behalf. “Is it that women cannot attain the fruits of awakening?” he asks. No, says the Buddha, women are equal to men in their capacity for awakening—that is not the problem (though he doesn’t articulate what is). Ultimately, he agrees to ordain Mahapajapati and her retinue. In very short order, every single one of them becomes enlightened.

But there’s a catch to the story—or rather, a detail that has become a catch in the intervening 2,500 years: according to the Vinaya, the monastic law code, as a precondition for ordination the Buddha imposed on Mahapajapati, and all subsequent nuns, a set of eight restrictive rules, known as the garudhammas, or “rules of respect.”

These rules unequivocally positioned women as subordinate to men in the monastic hierarchy. Rule 1, for instance, states that a nun, no matter how senior, must always bow to a monk, no matter how junior—even to one ordained “but that day.” In that first issue, the editors interpreted the rules, as Thich Nhat Hanh described them, as the Buddha’s temporary strategy to keep the brahmins from rising against him. But the garudhammas have proved quite durable, and in the quarter century since Tricycle first weighed in on them, bhikkhuni ordination and the status of female renunciates have become two of the most important and talked- about issues confronting contemporary Buddhists.

Scholars, both lay and monastic, generally agree that if the historical Buddha did insist on the garudhammas (that they were not, as some Vinaya experts have argued, a much later addition to the canon), he imposed them to keep peace with the society around him, where women were mainly chattel and the status quo would have been intolerably threatened by their departure for the spiritual life. The rules defined a second-class status for nuns that mirrored their position in the society at large, and by placating the laity, the theory goes, they made women’s ordination possible.

Related: Making the Sangha Whole Again

But in what has become a confounding irony, the rules seemed to make it nearly impossible to revive a lineage that has since largely died out. This perception zeroed in on the sixth rule, which requires the presence of elder bhikkhus and bhikkhunis to officiate at a nun’s ordination: “When, as a probationer, she has trained . . . for two years, she should seek higher ordination from both orders.” A nun, in other words, should not receive full ordination unless a retinue of both monks and nuns is available to grant her permission and officiate.

The garudhammas are still very much with us: they first appear, along with the nuns’ origin story, in the tenth chapter of a book of the Vinaya called the Cullavagga. They are subsumed under the 311 rules of monastic discipline for nuns (84 more than the 227 for monks), and they have outlasted the bhikkhuni lineage in most Buddhist places by a millennium at least. Invasions, wars, and famine, combined with the endemic subjugation of women in nearly every kingdom where Buddhist monasticism had thrived, wiped out women’s orders—around the 8th century CE in India, around the 11th in Sri Lanka, and likely in the 13th century in Burma.

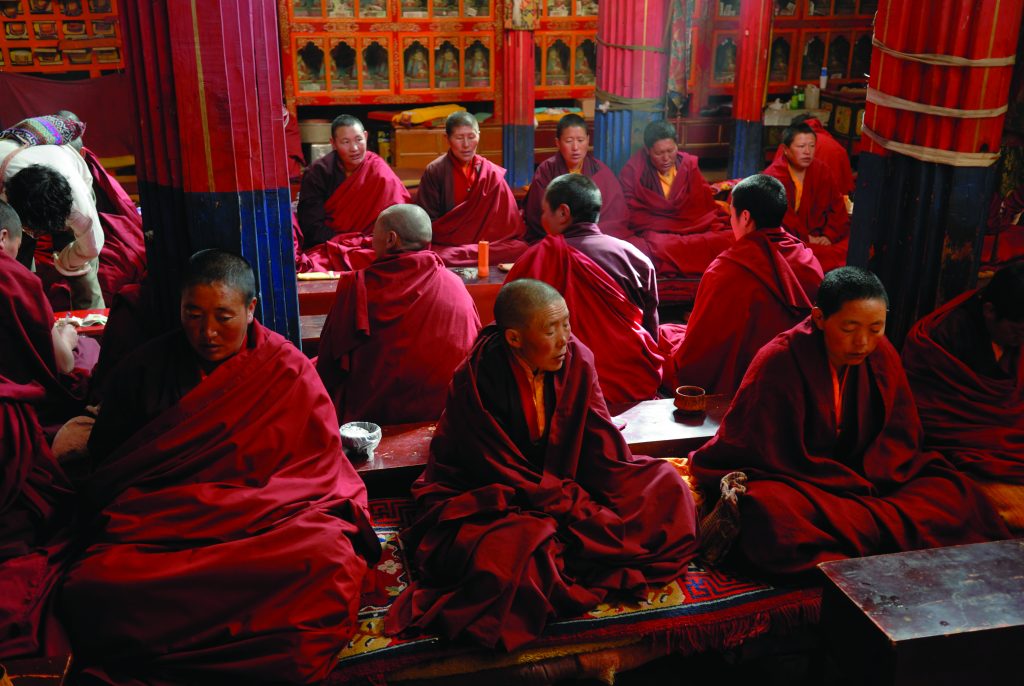

In the intervening centuries, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and Burma have not allowed full ordination for women, nor do Tibetan schools of Buddhism. China, however, is another story. Bhikkhuni orders there survived, and Mahayana lineages in the places where Chinese Buddhism spread, like Taiwan, Korea and Vietnam, have continued into the present.

“The Buddha gave full training to those who were hell-bent on Nirvana. Why shouldn’t we receive it?”

Indeed, in the 25 years since Thich Nhat Hanh’s story appeared, Buddhist women’s monasticism has undergone a sea change. Movements to resuscitate the bhikkhuni lineages have swelled and gained more traction than they’ve probably had, on an international scale at least, for centuries. Hundreds of women in Theravada and Tibetan traditions have taken full bhikkhuni ordination in Taiwan, with Chinese officiants and preceptors. In the late 1990s, a group of Sri Lankan women novices were ordained in India, with Chogye monks from Korea and Taiwanese nuns presiding. Since then, hundreds of nuns have ordained in Sri Lanka, arguably reviving the bhikkhuni order on the island. Even in Thailand, a country whose ecclesiastic leadership is resolutely opposed to nuns’ ordination (and where the female order may never have existed), women have begun receiving higher bhikkhuni vows.

From Asia, like the Buddha’s teachings millennia ago, the ordinations moved westward; by now they have become too numerous and varied to list. This is largely thanks to pioneering nuns and monastic scholars, such as Bhikkhu Analayo, Bhikkhu Bodhi, and Ayya Tathaaloka, an American nun in the Theravada tradition, who have parsed and reparsed the scriptures to get at the Buddha’s intention concerning nuns’ ordination. Bhikkhu Analayo in particular has laid out textual evidence that the Buddha left open the possibility for monks alone to ordain nuns in the absence of other nuns. In 2009, four women became full bhikkhunis in Australia in a Theravada “dual sangha” ordination (where both monks and nuns officiated). The following year, the United States had its first-ever dual sangha ordination of four nuns in northern California.

As women have ordained, they have also established nunneries—in the United States there are now roughly a dozen small hermitages, some with just one or two nuns in residence. Support and communications networks for bhikkhunis have evolved, too, an essential development given monastics’ dependence on lay support for their survival. Sakyadhita (the International Association of Buddhist Women), cofounded by the American nun and scholar Karma Lekshe Tsomo in 1987, has helped organize nuns’ ordinations over the past 25 years and in 2015 drew more than 1,000 nuns and laywomen to its biennial conference. The Alliance for Bhikkhunis, and now the Alliance for Non Himalayan Nuns, offer resources and guidance for aspirants and nuns on a scale that would have been unimaginable a couple of decades ago.

In the Tibetan monastic world, where women have historically been barred from full ordination and advanced religious study, nunneries and nuns’ education have grown exponentially. The Dalai Lama has said he believes women, in theory, are entitled to higher ordination; last year, Ogyen Trinley Dorje, the young 17th Karmapa, in defiance of tradition, announced that he intended to help restore the bhikkhuni sangha. “No matter how others see it, I feel this is something necessary,” he said. “As the Buddha said, the fourfold community [monks, nuns, laymen, and laywomen] are the four pillars of the Buddhist teachings.” Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, a veteran nun and currently president of Sakyadhita, has worked for decades on behalf of Tibetan nuns and to reinstate the lost togdenma (yogini) lineage. In 2000, she founded Dongyu Gatsal Ling, a nunnery where novices can both practice in seclusion and study with senior monks from nearby monasteries. In 2003, Thubten Chodron, an American who received full ordination in Taiwan in 1986, founded Sravasti Abbey in Washington State to train both male and female monastics according to Tibetan and Chinese vinayas. And the list goes on.

From conservative perspectives, like those prevailing in Thailand and among many Tibetan lineages, none of the contemporary bhikkhuni ordinations are valid. For Theravadins, rule 6 of the garudhammas has created a sort of chicken-and-egg dilemma, demanding that nuns exist in order for new nuns to be made. The legalist view holds that a woman from one Buddhist tradition ordained by monks or nuns in another invalidates the very notion of lineage. And by extension, “inauthentic” nuns cannot legitimately go on to ordain other women in their own traditions. In some places, women’s ordination is even considered a crime. In Burma (Myanmar), where female ordination is illegal, a handful of nuns have been jailed for ordaining in Sri Lanka; the Australian monk Ajahn Brahmavaso, who officiated at the nuns’ ordinations in Australia and northern California, was kicked out of the Thai Forest Sangha for violating Thailand’s 1928 “Sangha Act,” which forbids bhikkhuni ordination.

Related: The Story of One Burmese Nun

Even monks and laypeople who cleave to the notion that bhikkhuni ordination cannot and should not be revived agree that the future of the dharma hinges on the future health of monasticism. But without nuns, monasticism isn’t whole. The Buddha wanted a fourfold sangha. According to the canon, he told the demon-tempter Mara that he would not leave the world until all four were well established. Indeed, functioning monastic systems are imperative so that seekers, female and male, ready to dedicate their lives to awakening, have access to the full training and the best possible conditions for developing concentration and insight, unlatched from societal obligations and the sticky pull of worldly attachments. Laypeople need the possibility of excellent role models—well-versed teachers who have renounced the world in exchange for the dharma; experienced guides on the path to awakening for whom no conflicts of interest exist.

The Buddha, we know, was a radical. He upended the caste system at the very heart of the culture around him: rich or poor, educated or illiterate, upstanding citizen or seasoned delinquent—any sincere aspirant was eligible to enter the monastic sangha. Past karma, however onerous, can ultimately give way to one’s potential for wisdom, if practice is diligent and wholehearted—even if it takes lifetimes. Women are equal to men in their ability to awaken, he said. The mind is the mind. The radicalism of the Buddha’s approach permeates the customs of his enlightened disciples—the habits of mind and comportment that we practitioners are urged to emulate in order to live skillfully and to cultivate wisdom. It stands to reason that sexism and the oppression of women, in all of their multifarious, insidious guises, fly in the face of those customs.

The onus for reviving the bhikkhuni order, however, rests not only on the shoulders of monks who work the gears of the Southeast Asian and Tibetan monastic hierarchies. They are a key, just as are learned monks who can provide instruction and counsel to nuns and their emerging monasteries, as was done during the Buddha’s lifetime. But just like the laity surrounding the Buddha, whose opinions and needs played a large role in shaping the monastic rules, so we, as donors and supporters, have the power and responsibility to support the kinds of teachers we say we want. This is a quid pro quo writ large.

We may lack the ingrained, centuries-old cultural habit of supporting monastics, but nevertheless we need to put our money, and our hearts, where our mouths are. Plenty of us have jumped on the bhikkhuni ordination bandwagon, but the attentive generosity required to support a monastic community—support in perpetuity—is not yet keeping pace with our feminist, and humanist, enthusiasm.

Ayya Medhanandi, a Theravada nun who founded Sati Saraniya in Perth, Ontario, described the moment of her full ordination, in Taiwan, like this: “It was a lightning strike; I had this almost fetal recognition—as if an umbilical cord connected me directly to Mahapajapati. I was finally completely part of the Buddha’s monastic lineage.” As is true for so many women who want to ordain, her trajectory to full nunhood was no walk in the park: she practiced for decades as a renunciate in Burmese and Thai Forest monasteries, keeping the ten precepts, subsisting on alms food (and sometimes going hungry) until she ultimately answered a relentless inner calling.

After clearing a score of logistical hurdles, she took vows in an unfamiliar language and system, at the age of 58. But the lightning strike has continued to reverberate. “Since becoming a bhikkhuni, not only is the training ratcheting up my levels of renunciation, it’s also forcing me to be stronger than I ever imagined I could be,” says Ayya Medhanandi. “The Buddha gave the full training to those who were hell-bent on nirvana. Why shouldn’t we receive it?”

In the hagiographies of early Buddhist nuns, spiritual power is conveyed in glorious metaphors: enlightened women are great trees bearing heartwood, she-elephants that have burst their bonds, roaring lionesses who have sprung their cages. In fact, no textual record from an early civilization comes close to naming, and venerating, as many female spiritual masters as that of early Indian Buddhism—strong proof that women renunciates were identifiable and highly regarded. Thanks to that record, we can look to those long-ago sages, like Mahapajapati, for inspiration, to goad us toward that “fetal sense” of connection to the path. We can do what they did; we, too, can purify our minds and abandon the defilements that keep us shackled to samsara. But how much more inspired we could be with visible, contemporary women masters to emulate! The Buddha wanted us to have that, too.