“I NEVER KNEW A MAN,” Graham Greene famously wrote in The Quiet American, “who had better motives for all the trouble he caused.” After the disaster in Iraq, Greene’s 1955 description of an idealistic American intellectual blundering through Vietnam seems increasingly prescient. People shaped entirely by book learning and enthralled by intellectual abstractions such as “democracy” and “nation-building” are already threatening to make the new century as bloody as the previous one.

It is too easy to blame millenarian Christianity for the ideological fanaticism that led powerful men in the Bush administration to try to remake the reality of the Middle East. But many liberal intellectuals and human rights activists also supported the invasion of Iraq, justifying violence as a means to liberation for the Iraqi people. How did the best and the brightest—people from Ivy League universities, big corporations, Wall Street, and the media—end up inflicting, despite their best intentions, violence and suffering on millions? Three decades after David Halberstam posed this question in his best-selling book on the origins of the Vietnam War, The Best and the Brightest, it continues to be urgently relevant: Why does the modern intellectual—a person devoted as much professionally as temperamentally to the life of the mind—so often become, as Albert Camus wrote, “the servant of hatred and oppression”? What is it about the intellectual life of the modern world that causes it to produce a kind of knowledge so conspicuously devoid of wisdom?

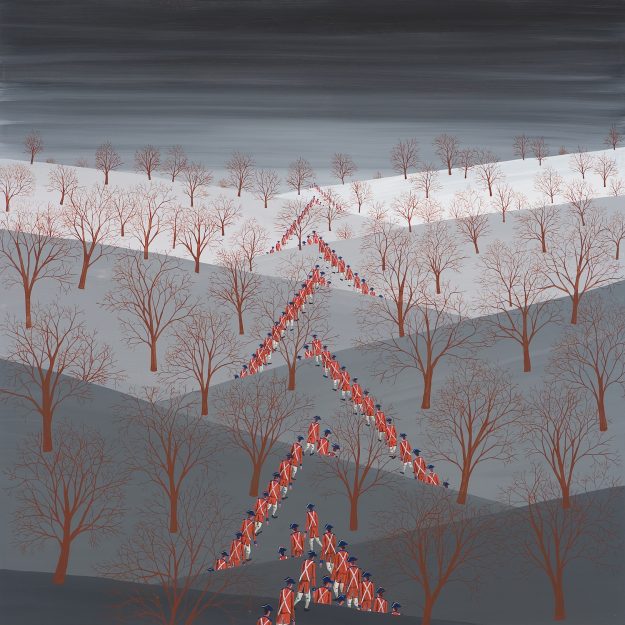

THE POWER OF secular ideas—and of the men espousing them—was first highlighted by the revolutions in Europe and America and the colonization of vast tracts of Asia and Africa, and then with Communist social engineering in Russia and China. These great and often bloody efforts to remake entire societies and cultures were led by intellectuals with passionately held conceptions of the good life; they possessed clear-cut theories of what state and society should mean; and in place of traditional religion, which they had already debunked, they were inspired by a new self-motivating religion: a belief in the power of “history.”

It took two world wars, totalitarianism, and the Holocaust for many European thinkers to see how the truly extraordinary violence of the twentieth century—what Camus called the “slave camps under the flag of freedom, massacres justified by philanthropy”—derived from a purely historical mode of reasoning, which made the unpredictable realm of human affairs appear as amenable to manipulation as a block of wood is to a carpenter.

Shocked like many European intellectuals by the mindless slaughter of the First World War, the French poet Paul Valéry dismissed as absurd the many books that had been written entitled “the lesson of this, the teaching of that” and that presumed to show the way to the future. The Thousand-Year Reich, which collapsed after twelve years, ought to have buried the fantasy of human control over history. But advances in technological warfare strengthened the conceit, especially among the biggest victors of the Second World War, that they were “history’s actors” and, as a senior adviser to President Bush told the journalist Ron Suskind in 2004, that “when we act we create our own reality.”

Many British and American intellectuals today help the reality-makers draw lessons for the present and future from the “facts” of history. In his book Surprise, Security, and the American Experience (2004), the Yale historian John Lewis Gaddis claims that John Quincy Adams in the early nineteenth century first articulated the “grand strategy” of preemption and unilateralism that President George W. Bush has adopted. Gaddis believes that the methods that established American hegemony and that “shaped our character as a people and nurtured our development as a nation” ought to be “embedded within our national consciousness.”

In Just War Against Terror: The Burden of American Power in a Violent World (2003), Jean Bethke Elshtain, the author of an estimable book on Jane Addams, invokes an even older tradition—Augustinian Christianity—as a moral and philosophical justification for a forceful American engagement with the world.

History as an aid to the evolution of the human race seems to be most fully worked out by the respected Harvard historian Niall Ferguson. Writing in the New York Times Magazine a few weeks after the invasion of Iraq, Ferguson declared himself a “fully paid-up member of the neo-imperialist gang,” and asserted that the United States should own up to its imperial responsibilities and provide in places like Afghanistan and Iraq “the sort of enlightened foreign administration once provided by self-confident Englishmen in jodhpurs and pith helmets.” In his recent book Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire (2004), Ferguson argues that “many parts of the world would benefit from a period of American rule.”

IT IS HARD TO IMAGINE now how this all began, how, in the nineteenth century, the concept of history acquired its significance and prestige. This was not history as the first great historians Herodotus and Thucydides had seen it: as a record of events worth remembering or commemorating. After a period of extraordinary dynamism in the nineteenth century, many people in Western Europe—not just Hegel and Marx—concluded that history was a way of charting humanity’s progress to a higher state of evolution.

In its developed form the ideology of history described a rational process whose specific laws could be known and mastered just as accurately as processes in the natural sciences. Backward natives in colonized societies could be persuaded or forced to duplicate this process; and the noble end of progress justified the sometimes dubious means—such as colonial wars and massacres.

This instrumental view of humanity, which Communist regimes took to a new extreme with their bloody purges and gulags, couldn’t be further from the Buddhist notion that only wholesome methods can lead to truly wholesome ends. It is in direct conflict with the notion of nirvana, the end of suffering, a goal many secular and modern intellectuals purport to share, but which can only be achieved through the extinction of attachment, hatred, and delusion.

Indeed, no major traditions of Asia or Africa accommodate the notion that history is a meaningful narrative shaped by human beings. Time, in fact, is rarely conceptualized as linear progression in many Asian and African cultures; rather, it is custom and religion that circumscribe human interventions in the world. Buddhism, for instance, in its emphasis on compassion and interdependence, is innately inhospitable to the Promethean spirit of self-aggrandizement and conquest that has shaped the new “historical” view of human prowess. This was partly true also for many European cultures until the modern era, when scientific and technological innovations began to foster the belief that man’s natural and social environment was to be subject to rational manipulation and that history itself, no longer seen as a neutral, objective narrative, could be shaped by the will and action of man.

It was this faith in rational manipulation that powered the political, scientific, and technological revolutions of the West in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries; it was also used to explain and justify Western domination of the world—a fact that gave conviction to such words as progress and history (as much ideological buzzwords of the nineteenth century as democracy and globalization are of the present moment).

The great material and technological success of the West, and the growth of mass literacy and higher education, produced its own model of the secular thinker: someone trained, usually in academia, in logical thinking and possessed of a great number of historical facts. No moral or spiritual distinction was considered necessary for this thinker; not more than technical expertise was asked of the scientists who helped create the nuclear weapons that could destroy the world many times over.

IT IS STRANGE TO THINK how quickly the figure of the spiritually-minded thinker disappeared from the mainstream of the modern West, to live on precariously in underdeveloped societies like India. It was left to marginal religious figures such as Simone Weil, Reinhold Niebuhr, and Thomas Merton to exercise a moral and spiritual intelligence untrammeled by the conviction that science or socialism or free trade or democracy were helping mankind march to a historically predetermined and glorious future. But then, as Hannah Arendt wrote, “The nineteenth century’s obsession with history and commitment to ideology still looms so large in the political thinking of our times that we are inclined to regard entirely free thinking, which employs neither history nor coercive logic as crutches, as having no authority over us.”

This kind of free thinking was more likely among people not entirely shaped by Western modernity; its most distinguished exemplar was Mahatma Gandhi, a devout Hindu who used the ideals of the ethical and mindful life to challenge the prestige and influence of many purely materialistic Western notions about the nature and meaning of human life. Gandhi claimed that his Indian ancestors had done well to ignore history and seek wisdom in theMahabharata, the epic account of a terrible war that is said to have occurred in India in the first century B.C.E. For, as Gandhi wrote in 1924, “that which is permanent and therefore necessary eludes the historian of events. Truth transcends history.”

Gandhi had little doubt about where this permanent and necessary truth of the Mahabharatalay. It had little to do with affirming the greatness of extinct empires and civilizations. The truth lay in the Mahabharata’s portrait of the elemental human forces of greed and hatred: how they disguise themselves as self-righteousness, and lead to a destructive war in which there are no victors, only survivors inheriting an immense wasteland.

As Gandhi saw it, there was no clear-cut good or evil fighting for supremacy in theMahabharata. The epic depicted a world full of ambiguities, where the battle between good and evil actually went on within individual souls, and where human beings had to make their own moral choices and strive for mindfulness and virtue. Though unconcerned with facts, theMahabharata taught the importance of an ethical life based upon constant self-awareness. History, Gandhi claimed, couldn’t do this, certainly not “history” as it is understood today, “as an aid to the evolution of our race.”

Though not an intellectual, Gandhi had an instinctive underdog’s suspicion of such grandiose Western words as progress and history. He knew that European empire-builders justified their worst excesses in Asia and Africa by invoking a particular history, in which they were always at the avant garde of humanity’s march to a glorious future. He could sense that a pseudoscientific history, one that justified foul means by positing noble ends, and that could be used to retrospectively justify past crimes and legitimize present ones, had become the primary ideology of the world-conquering nations and empires of the West. It was an ideology that—as Albert Camus wrote in The Rebel (1951)—”can be used for anything, even for transforming murderers into judges.”

FACED WITH THE INCREASINGLY bad news from Iraq and Afghanistan, such aspiring reality-makers as Ferguson appear to have faltered briefly before clamoring even more loudly for an assertion of American military might. “Give violence a chance,” they seem to say. If violence can’t remake the Middle East, then it can at least deal with Islamic fascists and terrorists.

By a perversity peculiar to our times, it is the advocates of nonviolent politics—of negotiation and dialogue—who face skepticism, if not outright derision. One of the commonplace rhetorical moves is to compare radical Islamism to German Fascism and then ask, “Could Gandhi have stopped Hitler?” But then Gandhi or his ideas weren’t much in evidence at Versailles in 1918, where Western nations imposed humiliating terms on the defeated Axis powers, setting the stage for another world war. Nonviolent principles of self-control, moral persuasion, and dialogue are unlikely to repair overnight the vast devastation wrought by a form of politics that institutionalizes greed, hatred, and violence.

It may be hard to conceive of nonviolence as a viable force, especially as we appear to be in the midst of a worldwide upsurge of violence and cruelty. Nevertheless, the history of the contemporary world is full of examples of effective nonviolent politics. The movements for national self-determination in colonized countries, the Civil Rights movement in the United States, the velvet revolutions in Russia and Eastern Europe, the end of apartheid in South Africa, and the gradual spread of parliamentary democracy around the world—the great transformations of our time—have been essentially peaceful.

And there have been activists and thinkers in our own time, such as Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., Thich Nhat Hanh, Nelson Mandela, Aung San Suu Kyi, and Václav Havel, who rejected politics as a zero-sum game (in which the other side’s loss is seen as a gain) and adopted moral persuasion and conversion as means to political ends. As the Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh wrote to Martin Luther King, Jr., after a spate of Buddhist self-immolations in Vietnam in 1965, “The monks who burned themselves did not aim at the death of the oppressors, but only at a change in their policy. Their enemies are not man. They are intolerance, fanaticism, dictatorship, cupidity, hatred, and discrimination, which lie within the heart of man.”

Imprisoned by the totalitarian regime of Czechoslovakia, Havel echoed a Buddhistic preoccupation with actions in the present moment when he warned that “the less political policies are derived from a concrete and human ‘here and now,’ and the more they fix their sights on an abstract ‘someday,’ the more easily they can degenerate into new forms of human enslavement.” In his own political practice, Gandhi opposed any mode of politics that reduced human beings into passive means to a predetermined end—it was the burden of his complaint against history. He insisted that human beings were an end in themselves, and the here and now was more important than an illusory future.

This has always baffled or disappointed those who measure nonviolent political action in terms of the regimes it changed. But for Gandhi, nonviolence was not merely another tactic, as terrorism often is, in a zero-sum game played against a political adversary. It was a whole way of being in the world, of relating truthfully to other people and one’s own inner self: an individual project in which spiritual vigilance and strength created the basis for, and thus were inseparable from, political acts. Gandhi assumed that whatever regimes they lived under—democracy or dictatorship, capitalist or socialist—individuals always possessed a freedom of conscience. To live a political life was to be aware of that inner freedom to make moral choices in everyday life; it was to take upon one’s own conscience the burden of political responsibility and action rather than placing it upon a political party or a government.

As Gandhi saw it, real political power arose from the cooperative action of such strongly self-aware individuals—the “authentic, enduring power” of people that, as Hannah Arendt presciently wrote in her analysis of the Prague Spring of 1968, a repressive regime or government could neither create nor suppress through the use of terror, and before which it eventually surrendered.

Many of Gandhi’s own colleagues often complained that he was delaying India’s liberation from colonial rule. But Gandhi knew as intuitively as Havel was to know later that the task before him was not so much of achieving regime change as of resisting “the irrational momentum of anonymous, impersonal, and inhuman power—the power of ideologies, systems, apparat, bureaucracy, artificial languages, and political slogans.”

This power, the unique creation of the political and economic systems of the modern world, pressed upon individuals everywhere—in the free as well as the unfree world. It was why Havel once thought that the Western cold warriors wishing to get rid of the totalitarian Communist system he belonged to were like the “ugly woman trying to get rid of her ugliness by smashing the mirror which reminds her of it.” “Even if they won,” Havel wrote, “the victors would emerge from a conflict inevitably resembling their defeated opponents far more than anyone today is willing to admit or able to imagine.”

THE WEST DID WIN the Cold War, in the wholly peaceful way that now makes its nuclear buildup appear even more insane, and now it claims to be fighting a new totalitarian enemy in the form of radical Islamists. The huge gulag archipelago Havel once said the West might build “in the name of country, democracy, progress, and war discipline” doesn’t appear likely now—at least not outside a few places in Iraq, Cuba, and Afghanistan. But it is not hard to discern through the fog of a war built upon half-truths, in the continuing deceptions and self-deceptions of ideologues and technocrats, the contours of what Havel called totalitarian power: “a power grounded in an omnipresent ideological fiction which can rationalize anything without ever having to brush against the truth.”

However, this fiction is always likely to be exposed as such by the objective reality of the world. Certainly, any government or religious-political movement aiming to achieve “full-spectrum dominance” through mostly violent means is not only morally null but also doomed to fail. The humanity it seeks to remold has grown much more various and recalcitrant since the long day of the last empire waned. As Paul Valéry warned, decades before the days of the Internet and Al-Jazeera, “the human mind is impotent before the political phenomena of our time [which] are accompanied and complicated by an unexampled change of scale, or rather by a change in the order of things. The world to which we, both men and nations, are beginning to belong is only similar to the world that was once familiar to us. The system of causes controlling the fate of every one of us, and now extending over the whole globe, makes it reverberate throughout at every shock; there are no more questions that can be settled by being settled at one point.”

Valéry asserted, unknowingly underlining a profound truth of Buddhist philosophy, that in an interdependent world “nothing can ever happen again without the whole world’s taking a hand” (Valéry’s italics) and for this reason “no one will ever be able to predict or circumscribe the almost immediate consequences of any undertaking whatever.”

Economic globalization has knit the world even tighter; and many people feel the interdependent nature of the world in their hearts. Yet many of the old secular ideologies—whether of the left or right—appear unable to phrase their longing for a knowledge that transcends personal and national self-interest and is not distinct from wisdom.

Many people have found in Buddhism—and in its suspicion of mental and intellectual abstractions—a practical way to resist the “power of ideologies, systems, apparat,bureaucracy, artificial languages, and political slogans.” But such is the hold of secular ideologies in the modern West that a mainstream intellectual invoking Buddhism would more often than not provoke the kind of derision reserved for anything vaguely religious or spiritual. It is a grim reflection on the life of the mind in the new century that while apparently respectable intellectuals recycle selective historical “facts” and line up to serve the manipulators of reality in the widespread trahison des clercs, a subtle moral philosophy such as Buddhism cannot speak its name in the public sphere.