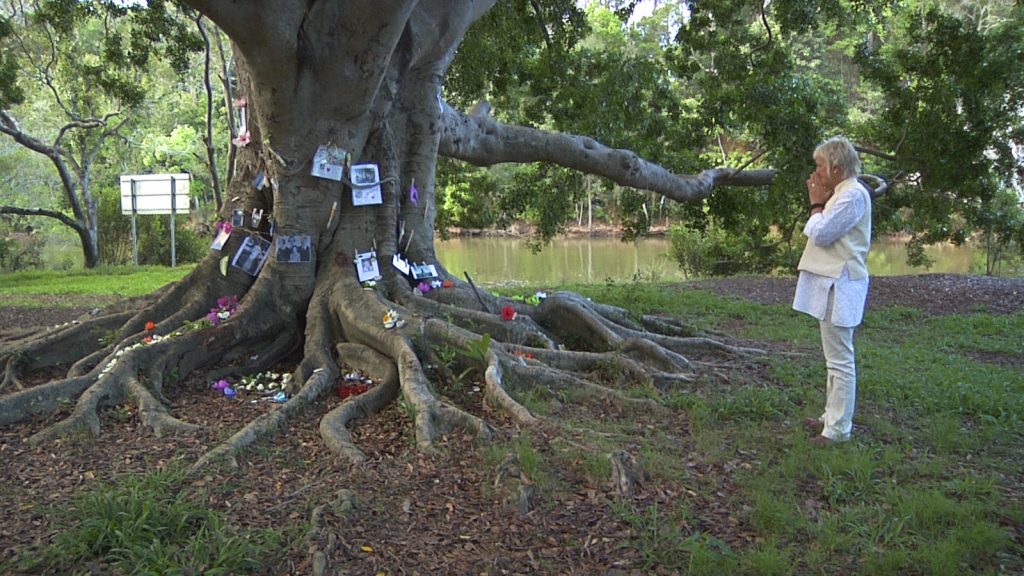

Zenith Virago describes herself as a “deathwalker.” Her job? To help families respond as well as they can to the loss of a family member or the shock of a terminal diagnosis, providing them with practical, legal, and emotional assistance. She also creates rituals to help families move through their bereavement by officiating funeral ceremonies, collective memorials, and “celebrations of the dead.”

This month, filmmaker Broderick Fox introduced Zenith’s life and work in a documentary called Zen and the Art of Dying. A pioneer of the Natural Death Care Movement, Zenith is on a mission to extend awareness of the death care movement, make nonprofit funeral services available, and to decommodify the funeral industry through DIY-coffin making and home funerals. By empowering people to take the process of dying back into their own hands, Zenith hopes to shed the stigma around death and dying and “return the wisdom of the infirm and elderly to the cultural conversation.”

It’s difficult to summarize all that you do. How do you describe it?

I work toward empowering people to die well. I avoid the term “good death” because it offers you its opposite—a bad death—which no one wants to have. And it can be a lot of pressure for people who are frightened and dying to then worry about whether they will have a “good death” as well. This is why I use the term “dying well.”

What I do is accompany someone on their journey, whether it’s the dying person who receives a diagnosis or the family of the dying person. I try to impart on them the information, education, awareness, guidance, and the wisdom that I’ve accumulated over 20 years of doing this.

In some ways, dying is like birth: you may have friends who have made a plan for a fabulous birth, but then life intervenes. It isn’t the plan that you wanted, but you just have to be with what is happening. By preparing for it and thinking about it, or creating a practice that makes you aware of death every day, you’re off to a good start.

What elements are important in preparing for the death of a loved one or yourself, in your experience?

An important thing is to communicate with family and friends. When you’re well, it’s easy to do: you might be driving in the car with a friend and they hear a piece of music and say, “Oh, I love this. I’d love this at my funeral.” But then if they receive a breast cancer diagnosis and you’re driving along and they say that, it’s a different story. You might not know what to say. It’s really great to start the conversation while you’re well so that it’s constantly in your awareness. Familiarity is a great asset when it comes to death.

One of the key things to remember is that death—for the person who is dying as well as the family— is an internal and external experience. On an internal level, death is full of emotions and acceptance or fears of the unknown. You won’t be there to support your children; you won’t be there to play with your grandchildren and give them the benefit of your wisdom. And there are external things like planning the funeral. When I go to speak with people, the beginning point for many of them is “we’ve picked the music for the funeral.” That’s great, and we’ll talk about it, but really when someone is ill or dying, they go to a discussion about a funeral because it’s familiar for them. What people aren’t looking at, though, is the step in-between. “Would I like to die at home? Would I like to be at the hospice? Would I like to be surrounded by friends or family? Would I like to have time alone?”

Yes, this sounds like Buddhist death contemplation: you meditate on a decaying corpse and on the inevitability of your own death.

Yes—but the emotional pain of dying is really about separating and leaving people behind. Friends are one thing, but when you’re connected to someone in your own family who is dying, it is interesting to watch your practice at that time to see if you can be present with what is. For people like me who have now lived a long time, we’ve had lots of incidents that give us an opportunity to polish our practice. When the intensity of a situation is over and you have time to breathe again, you may look back and say, “Oh, I really should have remembered that practice,” or “this time that practice supported me.” For some people, the experience of losing someone can be expansive, expanding, and heart opening. It’s very profound—you feel you’re really in the meaning of life itself. For others, it can be a contracting and fearful.

How is what you do different from palliative care?

It’s entirely different—people who do what I do are assisting people while they’re dying as well as assisting people to care for the body after their family member has died. Others help to build a coffin, wash and dress the body, put it in the coffin, and transport it. At this stage in the process, often the body will be cremated and the family will hold a memorial with the ashes. But a lot of people in this field, myself included, are finding that there’s a great benefit in having the dead body there to be with. When you hear the word “viewing” you think you’re just going to look at it. But if someone says, “let’s go and sit with Mom’s body,” then that’s a completely different action. You would expect to spend a bit of time there. And there’s often a transformation during this period of time; there’s a transmission of acceptance when you see that the body is just empty. Even small children will come up to a body and say, “Oh, that’s not Zenith. She’s not there. Where is she?”

In America, there’s no place for you to relax into the knowledge of the death. So, a lot of people in the Natural Death Care Movement are encouraging people to wash and dress the body, to have a period of time with the body—maybe two days or even half a day—and then let go when they’re ready. That time is incredibly precious and beneficial for everyone to really let their whole nervous system, their whole sense of reality, and their whole experience settle. They look back and realize that it’s the end of the dying process. I would really offer that to people in the U.S. This is what happens in other countries—in England and Europe, Australia and New Zealand, and other Western countries.

In the film, this was one of the things that really struck me. At the end, a man dies and his wife and children have laid out the body. There are flowers on the floor and they spend time with him. I imagine that if he had died in a hospital, they might have sped up this process to free up the space.

People feel they have to do the right thing when they’re in the hospital whether the hospital is busy or not. People are caught in that politeness. Whereas if you have the luxury of dying at home, that time is really precious and you can do whatever you’d like with it.

If you did want to learn more about this process—about taking care of your loved one’s body and handling their death yourself—where would you turn?

There’s an alliance called the National Home Funerals Association (NHFA) with members all over the U.S. But there are smaller organizations everywhere that are generally made up of people who have been home birth campaigners, as well as some nurses and palliative care workers who can see that the current system doesn’t support people. Some people have even worked in the traditional funeral industry and found it very disempowering. They’re all kind, helpful, and caring people, which can be difficult to find in the funeral industry. As you see in the film, they offer eco-friendly coffins and help the family during the time of bereavement and with the disposal of the body.

I recently taught at a workshop in Santa Cruz, and afterward, people said, “Wow, we had no idea all of this was possible.” This movement means that when you go to the funeral director, you won’t just take what they give you. You will be able to go in there armed with a list of questions about the services they offer, what is possible, and what you would like. It’s a bit like going to a travel agent. If you walked into a travel agent, you wouldn’t say, “Okay, what do I do?” You would say, “I want to go to Paris and I want to stay somewhere reasonable,” and the travel agent would give you some options. But the funeral director will, often, put you on a conveyor belt and at the end you get a bill.

In both the funeral industry and in medicine, we have so little information, and we entrust the process to experts in both cases.

Yes, you’ve got these medical programs with people wired up to machines. Every now and again, someone says, “No, I don’t want that. I don’t need to keep going with the chemo. I know I’m going to die—I want to have quality of the time I’ve got left.” And as soon as someone makes that decision, they’re on a different path. It’s not unusual. People do this every day. But families, I think, are so bombarded by the medical system’s idea that you have to keep people alive. So we really need to reclaim dying as a natural process. Death is not a failure. It’s actually our birthright to live well and to die well, even if we die on the side of the road.

Zen and the Art of Dying was released in Australia and New Zealand on Sept. 8. The film will be released worldwide on Oct. 8, 2016.