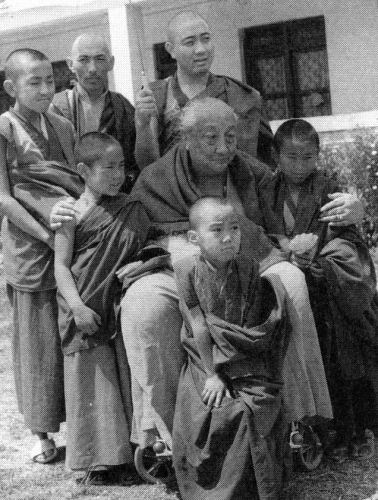

His Holiness Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche was one of the leading masters of the pith-instructions of Dzogchen (the Great Perfection), one of the principal holders of the Nyingmapa Lineage, and one of the greatest exemplars of the nonsectarian tradition in modern Tibetan Buddhism. He was a scholar, sage and poet, and the teacher of many important leaders of all four schools of Tibetan Buddhism. He passed away on September 27, 1991, in Thiumphu, Bhutan.

This interview was conducted by James and Carol George, who first met His Holiness Khyentse Rinpoche in Sikkim in 1968 while Mr. George was serving as the Canadian Ambassador to Nepal and the High Commissioner to India. In the following years, the Georges were fortunate to meet with His Holiness several times in Nepal, Bhutan, and later in Toronto and New York. Since his retirement from diplomatic service, Mr. George has been working with the Threshold Foundation, Friends of the Earth, and the Sadat Peace Foundation. Tulku Pema Wangyal Rinpoche was the translator. This interview took place in May, 1987, at Karme Choling Meditation Center in Vermont, where Khyentse Rinpoche had come to preside over the cremation ceremonies for Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche.

I suppose, even to begin an interview like this, we need to find a right attitude. Yes! Even for an interview right attitude is very important, especially for anything connected with a spiritual training. For example, when we pay our respects to a Buddha statue or we meet a highly accomplished spiritual master, our attitude is very important. The quality of our attitude can make all the difference in spiritual practice. In essence, a perfect attitude is to meet the teacher, receive his teachings, and put them into practice in order to perfect oneself to benefit all sentient beings.

We begin to know in the West that, in spite of amazing technologies, we are, in our inner life, living in a wasteland. How do you see us? What has gone wrong with us, and what, from your point of view, do we most need now? It seems very important for all of us to seek ultimate peace and freedom. If we are constantly being disturbed and losing our inner peace and freedom, what kind of happiness do we have, after all?

How can we begin the work of transformation? If we had to make a choice between outer pleasure, comfort and peace, and inner freedom and ultimate happiness, we should choose inner peace. If we could find that within, then the outer would take care of itself. Even when we have a comfortable and pleasant life externally, if our inner peace is shattered, or disturbed, we are not able to enjoy all that we have in our outer life. To make that transformation we find, when we think only of ourselves, and hold on to things, consider ourselves and our happiness as the most important thing, that it is the ego and its clinging that disturbs both the outer and the inner happiness. Even if we have a well-organized outer life, it can be very difficult for us to find inner happiness because we can never be satisfied so long as we have not cut the attachments due to ego. There is no end to it—it wants more and more—without any limit. The ego is insatiable. So it seems necessary to work on that, to free ourselves from ego, with the help of teachings, especially the Buddha’s teachings on this subject, in which we will find all kinds of ways and means of developing peace both externally and internally. Of course it is the inner that is important, not only for this life but for our lives to come, and not only for ourselves but for others too.

Tibetan Buddhism was created for very different conditions from those which exist in the West today. I am interested in your assessment of the future of Buddhism in North America and the main obstacles Westerners may experience in receiving it. The teachings of Buddha are not just for an immediate result but for a work that may last for many lives to come. The main obstacle in the East, as well as in the West, is that, if we check our habits that relate to our various negative emotions and positive emotions, we see that we habitually have much stronger negative emotions, and that we get distracted by them. So we hold on to our negative emotions very tightly and, especially in the West, many distractions result from that. We may have some interest and desire to practice but somehow we don’t (in the West) really see the importance of such training and how the teaching would help us progress and find lasting happiness and peace and liberation. But if we have a strong sense of what should be our main aim, and make efforts diligently, we can have a result in this present life.

Look at the lives of Milarepa and of the close disciples of Guru Padmasambhava, the great masters of the past. They could put almost 100% of their energy into spiritual training and within their lifetimes they could really see the quality and benefit of such a training unfold. But what happens to us? Even if we are interested and try to practice, it is rare for students to put even 20% of their energy into practice. Their distractions and habits are much stronger than their diligence.

This applies not only in the West but also in the East. What happens in the West is that there are many distractions, and even if there is interest, the quality and intensity of practice suffers, and we cannot put all our energy into it. And before even starting practice we already have an idea of the result we are working for—and that also spoils everything. Strong expectation without strong diligence is, it seems to me, a major obstacle, and at the same time a major danger for the Buddha dharma. Of course, the outer teachings from all the traditions will remain more or less available, but the inner and most profound—the direct transmissions—may be virtually lost. We live in a very difficult time, and it will become more difficult to find profound masters and to get in touch with such teachings. His Holiness the Dalai Lama and other great Tibetan masters have been doing their best—whatever they could—but although the external aspect of the teachings will continue, more or less, because there are many young lamas, the transmission that depends on inner realization will become more problematic and difficult, and mayor may not continue. So the main obstacle here, as I see it, is high expectations pursued without sufficient diligence in a setting of many distractions.

So the difficulties on the path are not so very different in America from those you experience with your own people? There are general obstacles and hindrances on the path that we find in the East as well as in the West. But in Tibet we had a training that was handed down over many centuries—a training that has been preserved in an intensive way, so that even though there are obstacles, the interest and wish to go through the training is so strong that somehow students manage to get through it, and even find that the obstacles can serve as a support for progress. In the West we find similar obstacles which make for blockages and hindrances on the path, and surely more distractions than in our part of Tibet. People know that they must expect obstacles, but they become so involved in them here that it becomes very difficult to overcome them. So there is a difference in the intensity of the problem.

Do you feel, in these circumstances, that any adaptation is necessary in transmitting Vajrayana to America? I know Trungpa Rinpoche must have been wrestling with this question all the time he was here. Yes, adaptation is necessary.

Certainly Trungpa Rinpoche’s own work in America was very difficult. Since you were one of his principal teachers, I would be interested to know how you see the way he carried out his mission here. Some of his actions have been judged negatively, and yet he touched tens of thousands of lives, especially among the young. How are we to understand such a teacher and his rather provocative behavior? The way he tried to approach the students in the West shows that he had the inner understanding of people and the best way to communicate with them directly, although there were hindrances and obstacles. To continue what he has started will be possible if there are beings like him who have the inner understanding and at the same time the skill in communicating with people. Then it should be possible to benefit beings in the best way; but it is difficult to find such beings.

You officiated at his cremation ten days ago and you composed a poem asking him to return quickly. And yet you teach, as I understand it, that there is no self. So what is there that can return, either as a Rinpoche or Tulku, or in the case of ordinary beings who are reborn? What is the nature of the self that can return? There has not been and will not be any such “self” or substantial entity which clings or is attached to one thing after another. But if you were to ask, “Well, what then is manifesting?” I would say that from the nature of emptiness (sunyata), great compassion manifests just as the sun manifests light. It unfolds by itself—no subject and no object. Out of compassion, those enlightened beings and masters manifest in response to the needs of beings who have already made, or are going to make, connections with them. For instance, His Holiness Karmapa is an enlightened being from the first Karmapa, so he does not have to come back—he just comes out of compassion in response to the needs of beings who have, or will have, a connection with him, for their benefit.

But, as regards the real nature of the self, one’s experience of awareness, especially at moments when I am more or less empty of thoughts and trying to bring body, speech and mind together (as you have been teaching), then there seems to be something behind it all that is an entity, that is not forever changing. Logically, a doctrine of impermanence means no self can exist, but isn’t that sometimes contradicted by our experience? Yes. There is a state which is beyond any concepts or thoughts, and which is inconceivable. Its nature is void and its expression is compassion, and when that great compassion manifests in response to the needs of beings there is—at the relative level—change and impermanence. But there is a state beyond the very idea of change or permanence. If we could reach that level, in that state we would find the “self” quite different from the idea we have now of, say, atman. The absolute truth is totally beyond any kind of concept and elaboration, such as existing and non existing, permanent and impermanence, and so on. So, in a way, we could speak of a “Great Permanence” as a metaphor to indicate the immutability of the absolute truth but in no way should this be understood as a permanent entity which could be labeled as “self” or atman, as this would again be falling into limiting conditions. It is unnecessary to postulate the existence of a self as the absolute nature is beyond all concepts. Limiting concepts and views, such as eternalism and nihilism, are the very root of delusion.

So practice then, is with the aim of connecting with that level beyond concepts? Yes.

It seems to me that the view being expressed is rather close to that of modern physics in the West, in which there is energy and space, and not much else. Mostly emptiness. Yes, rather close. The Buddhist view also says that when one tries to track the phenomenal world down to independent, truly existing and indivisible atoms, no such entities can be found.

I would also like to ask about suffering, because one of the primary motivations given for working on this path, with all the rigorous practices that are demanded, is to free ourselves from suffering. And yet I wonder whether higher beings do not, in a conscious way, suffer more intensely? It is important for us to know the nature of suffering in samsara; but knowing the nature of suffering is not enough. There is a difference between ordinary beings and those who are on the path. The latter can simultaneously know suffering and the emptiness of suffering that is the state of wisdom. It goes beyond, totally beyond, all suffering in the ordinary sense, and includes compassion which is stronger than suffering. So there is such a difference between those who suffer passively, without compassion, and those who experience at the same time compassion, born of wisdom.