It’s an invention that changed the world utterly, ushering in massive social change, splitting apart a religion once considered beyond question, and making the advent of Buddhism in the West possible. It’s movable type, and its story is well known, widely repeated—but often incomplete.

“A few records less, and we would not now be revering the Gutenberg Bible as his,” historian John Man has written about the 15th-century German printer Johannes Gutenberg. “All we would have would be the results: an idea that changed the world, and a book that is among the most astonishing objects ever created, a jewel of art and technology, one that emerged fully formed. . . .”

Books are astonishing pieces of art and technology. But they did not emerge fully formed from the mind of any one person. Rather, the arrival of mass-produced books relied on the actions of many people over centuries. Some of those people—and some of the oldest printed texts in the world—were Buddhist.

The history of mass printing in the West is often explained more or less like this: In the 1440s, a German man named Johannes Gutenberg founded a book-printing workshop. The book had become established in Europe long before, in the 4th century, but for a thousand years it could only be reproduced through impractical methods: either laborious hand-copying—which limited the number of copies and the diversity of the printed texts—or woodblock printing, which involved carving each individual page in one unchangeable piece. Gutenberg saw a way to revolutionize printing with movable type: individual, three-dimensional metal letters that could be arranged in a frame, covered in ink, used to print many pages in rapid succession, and rearranged in new frames as needed.

Gutenberg’s plan began bearing fruit in 1450, when he printed a short text. But it took till 1454 for his world-altering work to truly succeed. That year, he produced a complete Bible, 1,275 pages of 42 lines each. The print run of about 160 to 180 copies soon sold out.

With the success of the Gutenberg Bible, a new era in European history dawned. By 1500, printing presses had spread to 250 European cities. By 1517, when Martin Luther published his 95 Theses, those presses were producing a total of one million books per year. Luther was amazed to see his ideas spreading widely within weeks, an achievement that would have been impossible without mass printing. Two months after 95 Theses’ publication, Luther’s writing would begin to speed the transformation of Europe (and later the world) to the predominantly literate, information-flooded globe we know today.

Reviewing a few histories of the printed word could lead one to believe that is the entire story. In recent years, texts like Books: A Living History (2011), The Book: A Global History (2013), and The History of the Book in 100 Books (2014) have begun to address the full world-spanning scope of innovations that led to publishing as we now know it. But earlier books tend to gloss over non-European achievements. A 2001 volume called Five Hundred Years of Book Design, for instance, offers an insightful look at books and printing—but only in Europe. The same goes for the weighty, seemingly comprehensive The Nature of the Book: Print and Knowledge in the Making (1998).

What gets left out is startlingly rich. It involves a journey across nearly half the planet, from Buddhist countries to Muslim realms to medieval Christendom— and eventually to Buddhist temples today.

At the outset, metal movable type was devised not to promote Buddhism, but rather to protect it from invaders.

In the 12th century, the Mongol ruler Genghis Khan consolidated the largest empire in human history, an area stretching from Asia’s Pacific coast westward to Persia. After his death in 1227, his successor, Ögedei Khan, continued the conquest. In 1231, Ögedei ordered the invasion of Goryeo, the area now called Korea. The peninsula was then a rare strip of land not controlled by the Mongols. For 28 years, the Mongols mounted repeated attacks on the ruling monarchy. That government, the Goryeo dynasty, sought to repel the invaders, and also took pains to maintain and protect its greatest treasure— and that meant Buddhist teachings.

Korean people had been long aware of Chinese inventions with the written word. Since about the first century BCE, the Korean language had been written in a form adapted from the Chinese writing system. Moreover, Korea’s very first printed materials were brought from China. When China’s Song dynasty began to use a printing technique that involved chiseling entire pages of text into woodblocks (as well as a different, unsuccessful attempt at carving type into clay), the Goryeo dynasty knew about the innovation through imperial imports. In the late 10th century, printers in Szechuan, China, produced a 130,000-woodblock print of the vast Buddhist canon, the Tripitaka. In 1087, an attempted invasion by nomads called the Khitans prompted the Goryeo government to do the same.

Mongol invaders burned that Tripitaka Koreana to ash in 1232. The Goryeo dynasty redid the project, “as prayers to the power of Buddhas for the protection of the nation from the invading Mongols,” writes Kumja Park Kim in Goryeo Dynasty. By 1251, workers at the country’s Buddhist monasteries had carved the 81,258 wooden tablets necessary to reprint the full text of over 6,000 volumes.

In 1234, the Goryeo dynasty also commissioned a civil minister, Choe Yun-ui, to print another Buddhist text, The Prescribed Ritual Text of the Past and Present (Sangjeong Gogeum Yemun). That book was 50 volumes long and would have required a large number of woodblocks. So Choe Yun-ui came up with an alternative: altering a method used for minting bronze coins to cast individual characters in metal. These pieces could be arranged in a frame, coated with ink, and used to press many sheets of paper (or animal skin) in succession— like the woodblock process, but faster. By 1250, the project was completed. It was the first book ever printed in movable metal type—and it happened 200 years before Gutenberg.

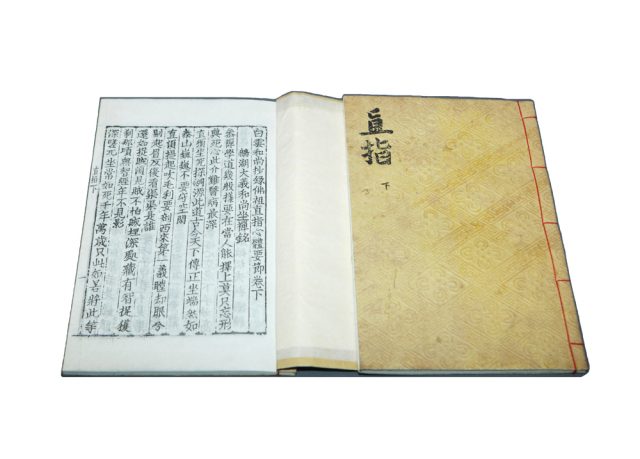

As the Mongol conquest continued, the Goryeo dynasty’s efforts to preserve its texts expanded. Unfortunately, no copies of the earliest printing work, including Choe Yun-ui’s project, have survived. Thus the oldest extant book printed with movable metal type is “The Anthology of Great Buddhist Priests’ Zen Teachings” (Baegun Hwasang Chorok Buljo Jikji Simche Yojeo, often simply called Jikji), dating to 1377— over 100 years after Choe Yun-ui’s Ritual Text, yet still nearly a century earlier than the Gutenberg Bible.

The Goryeo printing enterprise differed from Gutenberg’s work in two important ways. Both printing operations involved placing metal letters in a frame, inking them, and then pressing paper to the surface. But only Gutenberg’s method included mechanisms modified from wine or oil presses that allowed for lowering a metal frame over the top of the paper. This method was even, reliable, and fast. Goryeo printing, created in an area without such presses, involved pressing paper to the metal type by hand, a considerably slower method.

The Goryeo printing enterprise didn’t franchise into every town or branch into secular printing, either. In part, this might have been related to ongoing invasions. But it’s also due to the issue that stopped printing from becoming widespread in China: the logographic writing script then used in both countries. With each syllable represented by a different character, thousands of pieces of movable type were necessary to construct a text. The complexity was a block to efficiency, which meant printing was only feasible for a limited range of texts.

Nonetheless, movable type did find purchase elsewhere. The commander who ordered the invasion of the Korean peninsula, Ögedei Khan, was a son of Genghis Khan. A grandson of Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, ruled over the Yuan dynasty, one of four regions of the then hemisphere-wide Mongol empire. In the latter half of the 13th century, Kublai Khan situated himself in Beijing, surrounded by Buddhist and Muslim associates. There, he could have accessed information about Korean and Chinese technologies. Through trade with another one of Genghis Khan’s grandsons, Hulegu, who ruled over Persia and parts of central Asia, Kublai Khan would have also had a way to connect to a solution to the logographic printing problem.

On the old Silk Road, halfway between Beijing and the heart of what was once the Mongols’ hold in Persia, the Ilkhanate, lies the homeland of the Uyghur people. In his lifetime, Genghis Khan recruited many members of this Turkic ethnic group into his own army. By the 13th century, the Uyghur people were distinguished for their learned status, and the Mongols adopted their writing system: words written vertically, with an alphabet.

Through the Uyghurs, the Mongol empire thus had access to one crucial detail that had prevented printing in East Asia from creating explosive change. Scholar Tsien Tsuen-Hsien wrote in Joseph Needham’s Science and Civilization in China (1985), “If there was any connection in the spread of printing between Asia and the West, the Uyghurs, who used both block printing and movable type, had good opportunities to play an important role in this introduction.”

Did they in fact pass their technologies from East Asia to the West?

Thus far there is no clear historical evidence to support what some scholars have put forth as likely. It is certain that there was no explosion of printing in the Western Mongol empire: “there was no market, no need for the leaders to reach out to their subjects, no need to raise or invest in capital in a new industry,” as John Man points out in his book The Gutenberg Revolution.

Nonetheless, “Mongols just tended to take their technologies everywhere they went and become a part of local culture, sometimes acknowledged, sometimes not,” Colgate University Asian history professor David Robinson says. Christopher Atwood, a professor of Central Eurasian Studies at Indiana University, agrees: “Generally, if something is going from East Asia [westward], it would be hard to imagine without the Mongols.” And movabletype Uyghur prints have been discovered in the Uyghur homeland in northwestern China, indicating that the technology was used there.

The Mongols continued their advance, reaching Eastern Europe in the 13th century and carrying out military incursions there for over a century. By 1400, when Johannes Gutenberg was born, their innovations could well have spread to Germany and France, so that when a few investors—we would call them early capitalists—funded Gutenberg’s workshop four or five decades later, all the right technologies were at his disposal.

The Buddhist origins of movable metal type might not have mattered much to people who spread the technology worldwide. (Although long a Muslim people, Uyghurs had only just converted at the time of Mongol conquest. The religion they left behind? Buddhism.) But do they matter to Buddhists today?

Printing helped maintain Korea’s religion as Mongols took control of the peninsula. “There are several generations of very nationalist Korean historians who stress empathically that Korea may have been defeated militarily, but maintained its independence, its sovereignty, throughout the Mongol empire,” says Robinson. In fact, Korea did become a vassal state of the Mongol empire in 1259 and remained so for eight decades. And the Mongol invasion eventually replaced its Buddhist monarchy with what Robinson calls “a new kind of elite . . . based on merit, success in civil service examinations, and mastery of Confucianism.”

Yet the texts Goryeo aristocrats had printed stood against that sweeping change, and throughout that dark period the nation’s Buddhist canon remained firmly preserved. Printing has kept the religion’s vast canon standardized and accessible ever since, helping to make transmission of the dharma possible.

Understandably, then, Korea’s texts are also a point of modern national pride. Nothing of Choe Yun-ui’s metal-printed Sangjeong Gogeum Yemun survives, but several temples and museums in Korea still hold artifacts of early printing. “The Tripitaka Koreana is the only case in the world where the printed copies as well as the [woodblock] tablets were preserved whole,” says the Korean researcher Sang-jin Park; today those tablets are in Haeinsa, a Buddhist temple in South Gyeongsang province. In addition, the Early Printing Museum in Cheongju, Korea, maintains public awareness of the history of Korea’s printing technology. It also campaigns for the return of Jikji, the oldest extant pages of a book printed by movable metal type, to Korea. Around 1900, Victor Collin de Plancy, a French diplomat, purchased the pages; they were later donated to the National Library of France in Paris, where they were rediscovered by a librarian several decades ago and restored to their place in the long record of the invention of movable metal type.

1087 – The Goryeo dynasty—a monarchy ruling the area of the modern Korean peninsula—is prompted by attempted foreign invasion to produce woodblock carvings of the Buddhist canon, the Tripitaka.

1227 – Genghis Khan, Mongol leader of the largest consolidated empire in human history, dies.

1231 – Genghis Khan’s successor, Ögedei Khan, orders the invasion of the Korean peninsula.

1232 – Mongol invaders burn the Tripitaka to ash; in response, the Goryeo dynasty commissions a second printing project, “as prayers to the power of Buddhas for the protection of the nation from the invading Mongols.”

1251 – Workers linked to Korea’s Buddhist monasteries had carved all 81,258 woodblocks necessary for the full text.

1234 – The Goryeo dynasty commissions Choe Yun-ui, a civil minister, to produce a 50-volume Buddhist text, “The Prescribed Ritual Text of the Past and Present” (Sangjeong Gogeum Yemun).

1250 – Choe prints Sangjeong Gogeum Yemun in its entirety, using individual characters cast in metal and sheets of paper instead of woodblocks for carving: the first use of movable type technology (two centuries before Gutenberg).

1259 – Korea becomes a vassal state under the Yuan dynasty, one of the four divisions of the Mongol empire, and remains so until roughly 1339.

1377 – Decades after Korea’s 80 years under Mongol rule, the Goryeo dynasty produces “The Anthology of Great Buddhist Priests’ Zen Teachings” (Baegun Hwasang Chorok Buljo Jikji Simche Yojeo), the oldest extant book printed in movable metal type.

1400 – Johannes Gutenberg is born; Mongol elements of technological innovation infiltrate beyond Eastern Europe into Germany and France.

1440s – Gutenberg establishes a workshop and attempts to print a book.

1450 – Gutenberg creates several copies of short texts.

1454 – Gutenberg achieves world-altering technological success by producing a complete copy of the Bible, 1,275 pages of 42 lines each.

c. 1500 – Printing presses are established in 250 European cities.

1517 – Martin Luther publishes his 95 Theses.