For nearly two decades, multimedia artist John F. Simon Jr. has started his day the same way: drawing and meditating.

In the barn he’s converted into a generous studio space in Sugar Loaf, New York—about 60 miles north of Manhattan—Simon sits until a persistent image comes to him.

“My drawing practice often involves trying to intensify fleeting sensations. These states of mind seem to have more dimensions that I can simultaneously grasp. Mindfully making the marks on paper flattens the experience into a picture,” Simon said.

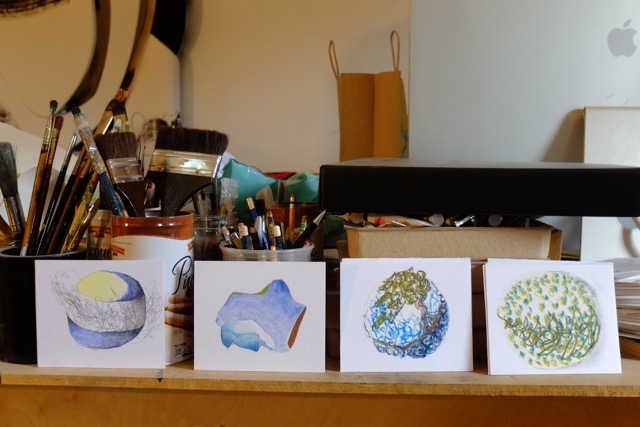

On his desk sit the 5-by 6-inch cards that he’s been working on, as well as multiple boxes that hold his archives. The images, which he calls “divination drawings,” are both abstract and realistic, executed in a mix of pencil, gouache, and charcoal. These drawings, according to Simon, are his “real work.”

Tall and soft-spoken with a Louisiana drawl, the 53-year-old-artist took a while to realize the true value of this routine that he acknowledges impacts every aspect of his life. Now, he’s sharing his daily practice with others in Drawing Your Own Path, 33 Practices at the Crossroads of Art and Meditation. The book, which is available on November 1, is part autobiography, part instructional guide, and includes exercises to help the reader explore a creative alternative to “straight meditation.” Simon writes succinctly about the doubts and insecurities that he has wrestled with as he forged his own path, refining the process of turning his interior monologue into art. Throughout, you sense the insatiable curiosity that has buoyed him up and produced extraordinary insights, corresponding with shifts in his artistic methods and intentions.

Early on, as meditative drawing became a habitual exercise, Simon sensed that it was more than simply a grounding force in his daily life.

“I became very committed to improvisation . . . I was experiencing or exploring a kind of ‘otherworldly’ sense about what appeared on the page,” Simon said. “I began to search for ‘explanations’ and that led me along a winding path that got traction in the [Theravada Buddhist text] Progress of Insight Path and [the Zen text] 10 Ox-Herding Pictures.” John Daido Loori’s translation of Riding the Ox Home was also seminal. The words and images seemed to Simon to carry equal weight, each capturing what the other couldn’t. They proved his gut feeling: that his daily meditation and drawing practice were integral to each other. In addition to providing personal insight, they enriched the way in which he experienced his art.

Around the same time, Simon came across Buddhist Geeks, an online mindfulness community that shared his fascination with the intersection of Buddhism and rapidly evolving technology. Soon he became a facilitator on their website, sharing his knowledge on drawing as a contemplative practice through talks and retreats that became the basis for his new book.

Right now Simon is preparing for his newest show, Endlessly Expanding, and his enthusiasm for the process is palpable. He points out the latest completed piece, part of his “expansion series.” Viewed from 20 feet away, the roiling 3D shapes appear to explode out of the gold frame. On closer inspection, the surface of the wall relief is marked with a mesh of fine charcoal lines. “When I draw on the surface, I try to reanimate it,” Simon said. “After all the production, I try to leave a lot of marks so that there’s a human touch there.”

The production Simon refers to is a multistep process. He spreads out his morning drawings and finds one that speaks to him.

What surprises me is that a very particular subject gets attached to each drawing. My subconscious mind is using the drawing to send signs to my conscious mind. What can’t get suppressed gets attention,” Simon said.

He scans the drawing and converts it into a 3D image using computer drawing tools. From there Simon digitally carves the shapes out of synthetic wood using a CNC router [a digital cutting machine], assembles the piece, and paints or coats the surfaces with plastic veneer.

“All of a sudden I have this object and then the depth, the dimensionality, the surface texture—all that comes into play. And that’s what gives it its energy,” he explains excitedly. The multiple layers of process find expression exactly in the art.

Simon was admittedly “not a child who could immediately draw well.” Coming from a family of mathematicians, John was fascinated by the power of computers from an early age. He arrived at Brown University in 1981 thinking he would study physics and photography, but soon found the geology department’s digital data from Mars more enticing. It was there that he learned how to write computer code.

John went on to receive a master’s degree in earth and planetary science, and then a master’s of fine arts in computer art.

“I was shooting between science and art for a really long time and it served me well—it gave me a way to make money and freelance for years. I wrote code for people’s websites. I could do things that at that time no one else could. And it kept me in New York and in a studio,” Simon said.

In the late 1980s, Simon started using coding in his art. “I wanted an idea for a unique drawing tool—something that could extend drawing in a digital way,” said Simon, adding that he created digital tools to create both specific marks and dynamic lines. Initially his works imitated classical drawing, but Simon found that the process for creating art on a computer was often more interesting than the end result. He began experimenting with the unforeseen results of his coding, allowing the work to find its own narrative—one that animated the process.

By the mid-1990s he was frustrated with the limitations of his medium—black and white images on paper. “When you use the drawing tools online they spin, they open, there’s all this activation and it’s fascinating. But when it got put onto paper . . . it was static again.” He was also feeling pressure to find something unique that the New York art market would respond to. And the answer was to make a computer screen his canvas.

“These became a kind of high-end, high-tech new kind of object,” Simon said. “And as soon as it was made we sold out.”

His “art appliances”—reconfigured laptop screens mounted in laser-cut plastic frames—were being snapped up by the likes of the Guggenheim, the Whitney, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Curators were fascinated by these pieces that could switch on and off, producing digital art-software cycles of endless combinations of pattern and color, and Simon found success as a forerunner in the software art market.

Once Simon’s career took off in the early 2000s, however, he was faced with a reality check: the peace of mind and satisfaction he’d anticipated as a result of his success was elusive. Still plagued by doubts about the direction his art was taking, Simon threw himself into an ambitious new project to try to create the world’s first autonomously creative artificial intelligence. His vision was to design a computer program that could innovate, and Simon’s research involved figuring out what rules he was unconsciously using to guide his own drawing—to get to the root of his desire to create—and turn those rules into code. Thus began his self-inquiry meditation through his daily drawing practice.

Taking a break from his studio, walking back up the meadow to the house, Simon explains how his research project ultimately failed to produce the code he’d hoped for. But the questioning revealed to him a deeper understanding of the crucial role the human mind plays in the creative process. The mind shows preference, distinguishing pattern from chaos, art from random marks. This insight allowed him the freedom to draw and his intuition to guide him.

“The stated goal was to create an artificial intelligence . . . but the self-observation led me to see that some of the things that were arising in the imagery persistently were mirroring my thinking, my state of mind, my emotional conditions. I started to be able to read these things in the drawings, and more deeply in the symbols that came up,” Simon said.

When the economy tanked in 2008, around the same time that flat screens started appearing in bars and elevators, Simon stopped making his art appliances entirely. He went back to fundamentals, often drawing for eight hours a day, and discovered something that had been staring him in the face all along. His small, impulsively done sketches from his morning drawing and meditation sessions held a treasure trove of insight and inspiration.

“It was just a mater of perspective to recognize that every drawing was a completely new thing,” Simon recalled.

The double-height living room of Simon’s home that he shares with his wife, Elizabeth, and their two children is empty of furniture—an ideal display space for Moment of Expansion, his recent piece that measures 9 feet by 16 feet. “I started to see these expansions. I started basically breaking out of the frame. And this corresponded with a whole period of spiritual growth and meditation and artistic growth. I started to really make work that I believed in, that I’d wanted to make my whole life and at the scale I wanted to make,” Simon said.

Simon’s work now appears in galleries and museums all over the world. But his spiritual growth has helped him come to terms with the idea that the creative process is an end in itself. He began to eschew market-driven decision-making.

“Now, while I do appreciate sales, I also have this whole online community that I work with. I do classes and we practice together. And there’s something more broadly satisfying about helping and sharing. That’s why I wrote the book,” Simon said.

What emerges from an encounter with Simon’s art—and his writing about it—is his restless questioning and exploration of not only the texture and physicality of his work but also his intensive embrace of the process he engages to make it.

Drawing Your Own Path is available from Parallax Press on November 1.