In meeting a man along the way, greet him neither with words nor with silence. Now tell me, how will you greet him?

— An old Zen koan

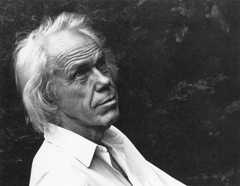

In the late 1960s, Minor White was fondly known as the Eastern guru of photography because of his unusual teaching methods, which included techniques borrowed from Eastern spiritual traditions. Over six feet tall, with a wild mane of silver hair, Minor was a magnetic and fascinating presence in the world of the arts.

When I first heard of him, Minor was teaching photography in the Architecture Department of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The Russians had just launched the Sputnik, and there was much criticism of America’s schools and universities because they seemed to be producing technicians rather than innovators. Minor’s job at MIT was to open up the students’ “creative side.” I began to follow his work through Aperture magazine and learned that he taught photography as a sacred art. The first time I saw one of his photography exhibits, I understood why.

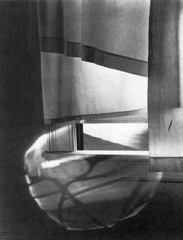

The exhibit, called “The Sound of One Hand Clapping,” was being shown in a small gallery in Massachusetts. Curious to see Minor’s work in person, I drove up from New York. What I saw moved me in a way I was totally unprepared for. Minor was a “straight photographer,” which meant he didn’t manipulate his images during the developing process. Yet Minor’s way of using natural light and shadows to produce a wide range of tonality in his prints was incredible. Looking at his photographs, I felt myself being thrust into another realm of consciousness. I realized then that there was a lot more to photography than I had previously imagined.

I started photographing when I was ten, and by the time I reached my mid-thirties, photography had become an integral part of my life. I had worked as a physical chemist for seventeen years, but had also started to teach college photography part time, and was seriously thinking of turning it into my profession. For a while my work as a research scientist was fulfilling, but at a certain point the questions that had led me to science to begin with became larger than their container, and I saw that they were fundamentally religious questions.

I began to systematically study the great spiritual traditions, trying to make sense of my life and the world around me. Unfortunately, by then I had become highly cynical, and much of what religion had to say seemed to me inconsistent with the realities of life in the twentieth century. I became opposed to organized religion, and turned into an avowed atheist. Yet many of my friends laughed and referred to me as “Pope John.” It was obvious to everyone that the passion that drove me was deeply spiritual, but I just couldn’t admit that to myself at the time.

One day in 1971, I received a letter from Aperture announcing a workshop that Minor White was giving in Lakeville, Connecticut. At first I was hesitant to apply because I didn’t think my photographs were good enough. But after some encouragement from friends, I sent in my portfolio—along with my date and place of birth so an astrologer could draw my chart. Although I was a resistant and hardened scientist, I wanted so much to study with Minor that I was willing to play along. He wanted to read my stars? Fine. He wanted me to read Carlos Castaneda’s A Separate Reality, Eugene Herrigel’s Zen and the Art of Archery, and Richard Boleslavsky’s Acting: The First Six Lessons? Fine.

I was accepted into the workshop, and a few months later I was on my way to the Hotchkiss School, where I and sixty other participants would spend a week studying photography with Minor White.

The first day began around four in the morning. I walked out into a large field with the others, wondering how in the world we were going to photograph in the dark. We were asked to stand in one long line and follow the instructions of a modern dance instructor who began to lead us through a series of movement exercises. I looked around, puzzled, but everyone was following, including Minor. I turned to the man next to me, “Why are we doing this? What does this have to do with photography?” “Ssshhhhh. Just do it,” he said. The young woman on my right said the same thing.

I thought I had been very patient up to that point, but this was just too much. I had paid hundreds of dollars to study photography. I wasn’t about to waste my time dancing in a field. Furious, I stormed away.

Back in my room, I started to pack my things, but the line of dancers in the emerging dawn caught my eye as I passed the window, and I decided to photograph them. I screwed a long telephoto lens onto my camera and began to shoot, feeling very pleased with myself. They can do whatever they want, I thought. I’m going to photograph. Thinking back on it, I realize that that was the perfect reflection of where I was at the time: standing apart from my life, staring at it through a lens, like a voyeur.

After the morning session was over, a group of students led by the dance instructor came to my room to convince me to stay. Though I was skeptical of Minor’s esoteric teaching methods, a part of me knew I couldn’t just walk away. I really wanted to learn to see the way he did, to capture my subjects in a way that didn’t render them lifeless and two-dimensional. I didn’t realize that Minor was teaching us exactly that: not only to see images, but to feel them, smell them, taste them. He was teaching us how to be photography.

I decided to stay, telling myself that I was doing it because my companions really wanted me to. The truth was, I felt moved by how much they cared. And so I woke up before dawn, meditated, and danced with everyone else. We didn’t even touch our cameras until about the fourth day, when Minor directed us to start working with the questions that had brought us there, by photographing them.

One assignment in particular had a profound effect on me: photographing our essence. “Your essence is the inner quality of being that has been with you since birth. It’s what you know as yourself,” Minor said. He asked that we go beyond our personality, the outward aspects of our being, and delve deep into the core of who we really are. In Zen terms, this question can be expressed as: “What is your original face, the face you had before your parents were born?”

As I packed my equipment, getting ready to go out, I had a hunch that this photograph was going to be the photograph of the workshop. In fact, I was so confident, so set on staying out as long as it took to come to full terms with the challenge, that I told a couple of people not to be concerned if I didn’t come back that night.

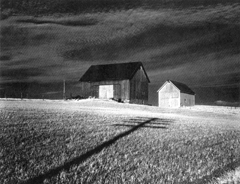

I set off early in the morning with a small backpack and my 4 x 5 camera. I walked through the woods slowly, without direction, trying to sense the subject that was supposed to find me. Minor’s instructions echoed in my mind: Venture into the landscape without expectations. Let your subject find you. When you approach it, you will feel a resonance, a sense of recognition toward it. If, when you move away, the resonance fades, or if it gets stronger as you approach, you’ll know you have found your subject. Sit in your subject’s presence and wait for your presence to be acknowledged. Don’t try to make a photograph, but let your intuition tell you the right moment to release the shutter. If, after you’ve made an exposure, you feel a sense of completion, bow and let go of the subject and your connection to it.

After a while I found a tree that seemed to beckon to me. I went to it and bowed. I set up my camera and then settled in front of that tree, waiting for my presence to be acknowledged. It was early afternoon; the sun had just passed its zenith. I sat with one hand on the shutter release, my whole body alert yet still.

That’s the last thing I remember.

Hours later I realized that the sun had set and the afternoon was turning cold. Time had completely disappeared for me. I stood up slowly, aware of the fact that I felt very different. My body and mind, my concerns had shifted. A lot of the questions I’d been struggling with all week had completely evaporated. I didn’t even know whether I’d taken a photograph. Somehow it didn’t matter.

I packed up my gear and headed back to the school, remembering that I had an appointment with Minor to talk about my work. When I arrived Minor was sitting on the porch outside his room, waiting for me, so I sat down with him. I had a list of questions I’d prepared two days before, but somehow all those questions no longer seemed relevant in the afterglow of my experience with the tree.

“What would you like to talk about?” Minor asked.

Embarrassed, I said, “Honestly, I don’t have anything to say.”

“Good. Then let’s just sit here together.”

So we sat in the quiet of the evening, until the next student arrived. I got up to leave, and Minor placed his palms together and bowed. I felt overwhelmed with a deep sense of gratitude that I didn’t know how I could requite. I told him as much, and he said, “You’re a teacher, right?” I nodded.

“Well then, teach.”

After that day in the woods, something in me had shifted, and for a while the world was right; I was right; everything was perfect and complete. Emotionally, creatively, I felt better than I had in years, and I wanted to be able to share that with others.

But this feeling didn’t last long. Slowly, over a period of a year, the buoyancy I had experienced began to dissipate. Frantically, I tried to recreate everything we’d done in the workshop in an effort to hold on to it. I read books on religion, spirituality, and philosophy. I practiced yoga, ate vegetarian food, meditated. I didn’t want those new feelings of clarity and resolution to disappear. What was it that had allowed me, for a moment, to become so thoroughly intimate with that tree, the world, and my life?

In 1972 Minor gave another workshop, at Pumpkin Hollow Farm, a retreat center in upstate New York. I went, but by then my admiration for my teacher had turned into resentment as I realized that my photographs were beginning to look like his. I felt stuck inside Minor’s head. What was my own way of seeing? Who was I?

Halfway into the workshop, Minor began to really push us on one of the exercises. We were already raw from much work and lack of sleep, and when Minor started to press a particularly fragile student, I lost my temper. As before, I ran away, but this time I began sitting zazen as soon as I got to my cabin. Sitting had been the one constant thread in my life since the first time I met Minor. It had become as natural to me as brushing my teeth, and when I went out to photograph, I often found myself sitting quietly in the woods, my camera next to me, unused.

After an hour or so of sitting, I returned to the workshop and found that the session had been successfully concluded and the room was quiet. Everyone was meditating. I apologized to Minor and took my place with the others.

A short time after the workshop, I wrote him a letter asking him if he would be willing to show some of his photographs from the “Sound of One Hand Clapping” exhibit in the gallery I had just opened. He not only agreed, but let me offer his photographs for sale at whatever price I wanted, and only asked for $25 each to pay for materials. I didn’t understand why he was being so generous to me, when I had shown him nothing but resistance.

I began to realize then that I needed a spiritual teacher, but I didn’t know where to turn. Minor had never presumed to be anything but a photographer. He used elements of the teachings of Gurdjieff, yoga, Zen, and mysticism in his workshops, but he never called himself a spiritual teacher. Still, I called him and asked if I could visit him. He was still teaching at MIT, so a couple of weeks later, I drove to Cambridge and met him at his house. We drank a bottle of wine and talked of many things. I didn’t ask for advice and he didn’t offer any, but when I left him I was feeling confident again. As I drove back to my hotel that night, I couldn’t stop thinking about our meeting. He really hadn’t said anything to me, yet something had shifted in me again. Why?

When I entered the hotel, I noticed in the lobby a poster advertising a conference called “The Visual Dharma.” One of the speakers was Trungpa Rinpoche, who was acquiring a reputation in the West as a powerful teacher of Buddhism. I decided to go to the conference, and through a series of events met my future teachers: Eido Shimano, Soen Nakagawa, and my transmission teacher, Taizan Maezumi. Gradually, Zen became the central aspect of my life.

The questions I had carried with me through all these years began to crystallize into an urgent need to understand the nature of my self. Something had happened that day in the woods during Minor’s workshop. What was it? And why did I feel so at ease in the presence of someone like Minor? I had to know. I kept searching, and that search led me to become ordained as a Zen monk and, finally, to turn myself over entirely to the religious life.

Reflecting back, it’s clear to me that the arts provided a beacon that guided me through the dark places of my spiritual journey. It would have been impossible for me to enter Zen training through the front door of a monastery. I’m still impressed when I see people who are able to do that. Just the sight of shaved heads and robes was enough to turn me off. But, as things would have it, I was able to enter through the back door and, ultimately, to be able to engage fully in spiritual practice.

The spiritual journey is long and sometimes lonely. But some of us are fortunate enough to encounter a person of the Way along the Way. I am indebted to Minor for first opening the door, and for accompanying me during part of my journey.