Anyone who has spent more than a few minutes in Japan, even if only changing planes at Narita, has encountered manga, those thick tomes of monochrome comics that someone always seems to be reading there wherever you look. You see dark-suited salarymen flipping through manga on the train to work and uniformed schoolgirls clutching manga on their way to class. There are manga about superheroes, of course, but others feature sports, gambling, war, romance, parenting, and almost every variety of sex, with titles geared to everyone from children to pensioners.

America has nothing like this diversity and ubiquity of comics. But next year marks the twentieth anniversary of Alan Moore’s Watchmen series, a groundbreaking deconstruction of the superhero ideal that launched something of a comic book renaissance here. Along with Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns (a noir retelling of the Batman story) and Art Spiegelman’s Maus (a Holocaust survivor’s tale recreated in comic book form), Watchmenspawned a new wave of serious American comic books that appealed to adults as well as children. This in turn has led many readers in the States to explore the Japanese phenomenon of manga. Now, with the publication of volumes 7 and 8, all eight volumes of Osamu Tezuka’s epic manga series Buddha are available to the English-speaking world.

Osamu Tezuka is known in Japan as manga no kamisama, the god of manga. Born in Osaka in 1928, he began drawing comics after the Second World War. Although trained as a physician, his innovative drawing style and creative stories quickly catapulted him to the forefront of the burgeoning manga industry. Before his untimely death from cancer in 1989, he had written well over 500 works, comprising more than 150,000 pages, plus several much-loved animated TV series and feature films.

Buddha is Tezuka’s reimagining of the story of Siddhartha Gautama from his birth in Lumbini to his years of seeking, enlightenment, teaching, and eventual death. But the Buddha is only one of many characters populating these pages, and his story represents less than a quarter of the material (even less in the first volumes). The rest is a richly constructed fantasy world of thieves and soldiers, royalty and slaves, sorcerers and ascetics, set against a backdrop of the ancient feuding kingdoms of Magadha and Kosala. These three thousand pages show us love affairs, betrayals, wars, and plagues, all the while tracing one man’s path to find truth.

There are many departures from the Buddhist canon, both small and large, as Tezuka blends his own fictional world with Buddhist tradition. Buddha’s birth is presented as more ordinary than miraculous, for example, and Tezuka has the Buddha’s mother die in childbirth. In other places, Tezuka plays with the literal words of the sutras, such as having the Buddha preach to an audience of actual deer in his sermon at the Deer Park. Tezuka takes even greater liberties with other characters of Buddhist lore, so that many with familiar names behave in unfamiliar ways: Ananda, for example, starts life here as a petty thief.

Caste is a recurring theme in the early volumes, emphasizing the radical social implications of the Buddha’s teachings. Even the young Siddhartha of volume 2 refuses to accept the caste distinctions the local holy men teach. Enumerating the four traditional Indian castes, he insists: “Brahmin, kshatriya, vaishya, or shudra, we all must die one day!” Several key characters are born slaves or outcastes, and Tezuka vividly illustrates the cruelty of such institutionalized bigotry and champions the fundamental equality of all people. The inherent value of animal life is another preoccupation, with human characters scolded several times for abusing our fellow species.

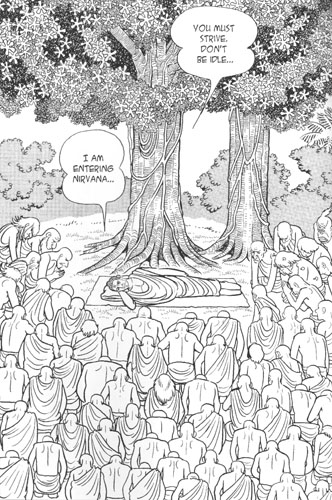

As the series progresses, the emphasis shifts from Buddha’s life to his teachings. The Eightfold Path and the Middle Way are each succinctly explained in volumes 4 and 5. “It is vulgar folly to indulge desire, and to drown in play,” Siddhartha explains even before his enlightenment, “but to fall in love with suffering, and to drown in it, is just as foolish.” Although the Buddha occasionally sounds a little overexcited in these pages, his later speeches introduce a lot of core Buddhist doctrine in very simple terms. “Empty your thoughts and forget even yourself,” Buddha explains to a group of ascetics in volume 6. “Then your doubts and worries will disappear, you will suffer less, not more, you will even merge with nature!” The series is rarely preachy, but adults and adolescents new to Buddhism will gradually learn the basics. Interspersed throughout are some clever (and a few not-so-clever) puns and visual jokes. Even Tezuka himself makes an unexplained appearance, wearing his trademark beret.

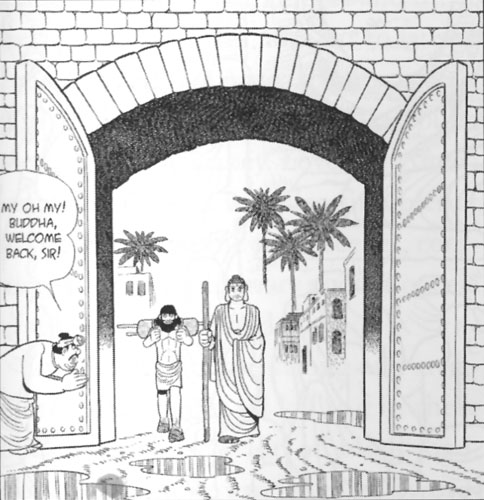

The artwork is an intriguing mix of gorgeous Himalayan landscapes and more conventional comic book action. The books are filled with Tezuka’s pioneering cinematic techniques, employing all sorts of close-ups, zooms, bridging shots, and pans, often with little or no dialogue. This makes them quick reads, despite their length. The characters themselves are drawn in what has become a fairly standard manga style, with large eyes and other exaggerated features familiar to fans of Japanese anime. Animals are treated with a particularly cartoonlike touch reminiscent of Disney. Lovers of American comic books will also find plenty of the usual graphic fight scenes, complete with the obligatory onomatopoeia of thok, krak, klak, and kapow.

In fact, despite the strong and articulate case against all killing in these books, there is a lot of bloodshed. Countless people are felled by sword, spear, or arrow, and there are a few scenes of torture and sadism (one young woman is deliberately blinded with a burning torch). None of this is particularly gory (probably in line with American comics), but there is an awful lot of it. And humans have no monopoly on suffering in these pages: one of the most heartbreaking scenes shows a lioness witnessing her cubs devoured by a snake. All this violence, plus quite a bit of partial nudity, probably makes the books inappropriate for younger children.

Buddha is only one of several masterworks written by Tezuka. Others include the highly spiritual linked stories of Phoenix (gradually being published in English by VIZ Media) and the Second World War saga Adolf (published in English by Cadence Books in 1995). Those who enjoy Buddha will like those as well; Adolf in particular provides an interesting counterpoint to Maus, covering similar ground in a very different way and demonstrating the vast range of approaches to such a difficult subject that are possible within the comic form.

Comic books are not the ideal medium for teaching the dharma. Their swashbuckling action inevitably creates something of a mixed message about violence, and the subtlety of Buddhist practice is difficult to reduce to such short dialogues. But Osamu Tezuka nevertheless demonstrates in this great series that manga can communicate serious ideas. The books are beautifully produced in elegant (though expensive) hardcover editions that do justice to Tezuka’s meticulous drawings, and the translations feel fresh and natural. As the manga authority Frederik L. Schodt writes in his treatise Dreamland Japan (Stone Bridge Press, 1996), “Tezuka was engaged in a lifelong quest to discover the meaning of life,” developing a philosophy of “Tezuka humanism” that draws heavily on traditional Buddhist ethics. It’s hard to imagine any reader–whether thirteen, thirty, or well beyond–not coming away moved by this captivating rendition of Buddhism’s most fundamental story.

BUDDHA, VOLUME 7: PRINCE AJATASATTU

Osamu Tezuka

New York: Vertical, Inc., January 2006

420 pp.; $24.95 (cloth)

BUDDHA, VOLUME 8: JETAVANA

Osamu Tezuka

New York: Vertical, Inc., January 2006

368 pp.; $24.95 (cloth)