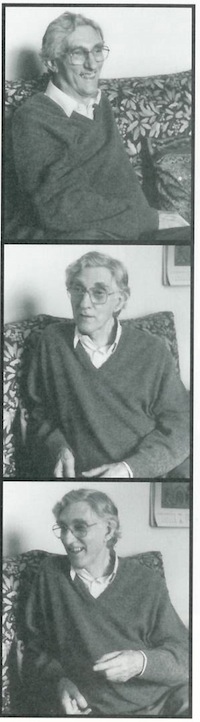

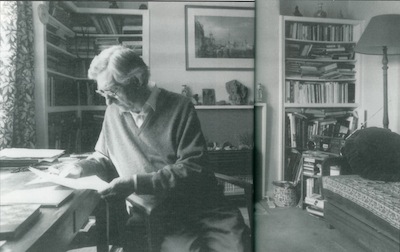

Born Dennis Lingwood in London in 1925, Sangharakshita was stationed in Sri Lanka and India during World War II. He remained in India after the war, and was ordained as a Buddhist monk in 1949. Returning to England in 1964, he founded the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order (FWBO) three years later. Today nearly six hundred men and women have been ordained in the Order. While most of its activities are based in Britain and among the ex-untouchable communities in India, there are a half-dozen centers in the United States as well. This interview was conducted by Stephen Batchelor, a contributing editor to Tricycle, at Sangharahshita’s apartment in Bethnal Green, London, in April 1995.

Tricycle: In 1949 in Kushinara, India, you became one of the first Westerners to have been ordained as a Buddhist monk. What led you to take this highly unusual step?

Sangharakshita: At the time it didn’t seem unusual at all. I was quite unconscious of being one of the first Western Buddhists to take monastic vows. It seemed the natural culmination of a whole series of developments that went back to my realization a few years earlier that l was a Buddhist and always had been one. I simply thought that to devote oneself to Buddhism meant becoming a monk, being a full-time Buddhist with no other real interests. But I also realized that it would be a very demanding life, and I wasn’t sure whether l was capable of it. So I wanted to test myself first.

Tricycle: How did you do that?

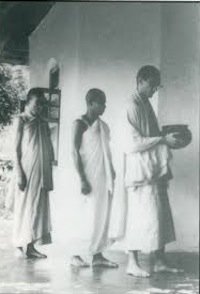

Sangharakshita: In 1947 I took up the life of an anagarika, which I would describe as a “freelance wandering Buddhist monk,” without formal ordination. For two years I led that wandering life. I was trying to live as I thought a Buddhist monk should, with an absolute minimum of possessions. Everything I owned was contained in a small cloth bag: one or two robes, a couple of books, and a brass pot. And I was meditating, sometimes in ashrams, sometimes in caves, studying the dharma, reading whatever Buddhist books came my way. Then l had a visionary experience, which convinced me that the time had come for me to seek ordination. Rightly or wrongly, I wanted to put an official stamp on my status as someone totally committed to the pursuit of the Buddhist path.

Tricycle: After your ordination you settled in the Himalayan town of Kalimpong, where you lived as a Buddhist monk for many years. How did your monastic role function as a basis of your study or practice?

Sangharakshita: Before going to Kalimpong, I spent time in Benares with my teacher, Bhikkhu Jagdish Kashyap. It was he who took me to Kalimpong and instructed me to stay there and work for the good of Buddhism. At the same time I kept up my practice of meditation and my study of the scriptures. I also started teaching, even though I was quite inexperienced as a monk. At the age of 25 l was not only still finding my feet as a monk, but I was also trying to spread the dharma in India.

Tricycle: To what extent did being a bhikkhu play a role in those activities? Couldn’t you have done such work just as effectively as a layperson?

Sangharakshita: I think people took me more seriously because I was leading a strict, austere life. During my early days in Kalimpong, for instance, I was still begging for my food; this impressed some people. I was also vegetarian and didn’t handle money. Because of the organizational activities l was involved in, l eventually found it difficult not to deal with money. So with some reluctance I started handling it again.

Tricycle: It’s generally accepted that Buddhist monasticism, especially at the outset, is an experience of community life. Were you not drawn at any time in that early period toward entering a monastery?

Sangharakshita: I don’t think l really was. During the war I was stationed in Sri Lanka and had an admittedly limited experience of Buddhist monasticism there. But what l saw of the bhikkhus did not impress me at all. I also had close contact with a lot of Thai Buddhist monks in India. But I’m afraid I was never very impressed. I don’t like to be too critical, but they seemed very easygoing and without much enthusiasm. I saw no evidence that I would gain very much by going to live in a Buddhist country as part of a monastery. In any case, my teacher had asked me to stay in Kalimpong.

Tricycle: How do you account for Buddhist monasticism, at least as you experienced it, as having evolved in such a uninspiring way?

Sangharakshita: Initially, the Buddha’s teachings had to be preserved through memorization and oral repetition. That was more easily accomplished by full-timers. So the monks inevitably gained a son of monopoly. The original Buddhism was a sort of forest tradition, or freelance monasticism. “Settled monasticism” was a much later development. It was the settled monastics who evolved the formalized Vinaya [monastic code] and sharpened the distinction between themselves and the layperson, on the one hand, and the forest renunciate, on the other. In fact, they almost swallowed up the forest tradition. The settled monastics of the Theravada countries, and even in some Mahayana countries, became part of an establishment. The Buddha himself was very critical of many aspects of the establishment of his time. His forest renunciates belonged to a wandering tradition that was non-establishment, even anti-establishment. That is part of my critique of much contemporary Buddhist monasticism: though the monks may be very worthy and revered, punctiliously observing all sort of rules, they’re really just part of the establishment of that particular country. In many cases they’ve lost the fire and inspiration that a monk should have. A necessary component of monasticism must be its critical edge, perhaps even a conscious anti-establishment stance. What I call “freelance monasticism” applies to all Buddhists who have this sort of critical edge. This is all the more so with the monastic who, due to his celibacy and not having a formal career, separates himself much more from the establishment and the existing society.

Tricycle: You’ve often spoken in your writing about the need to create a “new society.” In that new society, would the authentic monastic be anti-establishment?

Sangharakshita: lf there really were a new society, you wouldn’t need that anti-establishment element. Even though we aim to create a new society, there will always be a tendency for the new society to become another version of the old society. Therefore in our spiritual life we must keep up a constant self-criticism. During the Order and Chapter meetings in the FWBO we have confession and mutual giving of critical feedback precisely to keep one another up to scratch.

Tricycle: In your book The History of My Going for Refuge, you speak of your growing realization that the centrality of Buddhist life is going for refuge in the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha, rather than observing the monastic rule. When you first met lay Nyingma teachers in Kalimpong, you wrote, “I came closer to seeing that monasticism and spiritual life were not identical, and closer therefore to realizing that what really mattered was not whether one was a monk or a layman, but the depth and intensity of one’s going for refuge.” What were some of the factors that led to this shift in emphasis?

Sangharakshita: What struck me when l used to visit Dudjom Rinpoche [the late lay Tibetan master] was how all the people around him—monks, laymen and women, incarnate lamas—seemed to be on a level of equality. A very friendly feeling existed between them all regardless of their ecclesiastical status. As a relatively young monk this struck me deeply and had a strong effect. You would never have found that in the Theravadin context l was familiar with. Many of the Theravada bhikkhus who insisted on being treated with the greatest respect by laypeople were sometimes not as spiritually worthy as some of the laypeople who were bowing down to them.

Tricycle: So it was in this milieu that you began to question what was central to Buddhist commitment and the Buddhist life.

Sangharakshita: To a greater extent I was concerned with the question: What is it that makes one a Buddhist? I came to the conclusion that it is that one goes for refuge to the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha and accepts the precepts. While the formulas of going for refuge and taking the precepts were often repeated by the Theravada Buddhists I knew, they did not seem to be taken very seriously. I saw that this was because of their overemphasis on monasticism in the purely formal sense.

Tricycle: Eventually you concluded that going for refuge was what it meant to be ordained as a Buddhist. Was this not a considerable departure from tradition?

Sangharakshita: Yes and no. I came to see that there were different levels of going for refuge. In the Pali scriptures one saw people having an insight as a result of the Buddha’s teaching, and then they go for refuge. This is what I would call the “real going for refuge”—that which involves an experience of the transcendental. Yet I also observed that there were many sincere Buddhists who just tried to make the Three jewels central in their lives and went for refuge. So l spoke of that as “effective going for refuge.” And when one was recognized by other Buddhists as effectively going for refuge, that I considered to be synonymous with ordination. So in the FWBO, ordination consists in the recognition by others, especially senior and experienced order members, that a particular person has reached a point of at least effectively going for refuge.

Tricycle: In founding the Western Buddhist Order in April 1968, you departed from the Eastern Buddhist tradition in giving, for example, equal standing to men and women. You recognized the need for “a more unified order.” Nonetheless you still conferred the lay (upasaka) vows and maintained the distinctions between lay and monastic. How did you move from that position—which seems like sort of a modification of what was in place in Asia—to an order of dharmacharis, whom you describe as being neither monk nor lay?

Sangharakshita: Initially, male Order Members were called upasakas, and females upasikas. Then it became clear that our Order Members in India among the ex-untouchable community were neither upasakas in the traditional sense, nor were they bhikkhus. We needed to distinguish them both from the subordinate role implied by the term upasaka in Asia and from the largely ceremonial role of the bhihkhu. A new term was needed. Dharmachari is a term I took from the Dhammapada: “one who fares in the dharma.” Likewise, if one thinks of ordination in terms of going for refuge, then it is clear that women go for refuge just as much as men. If effective going for refuge equals ordination, then women can be ordained on the same footing and on the same level as men. It’s as simple as that.

Tricycle: Part of the difficulty in establishing Buddhism in the West is the tendency to reductively identify the dharma with, say, the practice of meditation. But it seems that over time people find the practice of meditation in itself is not enough.

Sangharakshita: One of the points that emerged from my recent discussions with Buddhists in America was that not enough emphasis had been placed on what we call “horizontal spiritual friendship.” Instead the emphasis tends to be on the relationship with the teacher—what we call “vertical spiritual friendship.” One of the practical consequences of this has been that when a teacher has died, the people who were supposed to continue his tradition found out that they hardly knew one another; of course, difficulties arose. So, in the FWRO, we stress both equally: your friendships with those with more experience than yourself as well as with those who are roughly at the same level. It is important to have strong spiritual friendships—not spiritual in the rarefied sense, but in a really down-to-earth way, to have good friends in the dharma with whom you can talk things over, share experiences, share difficulties and whose spiritual support you’re assured of.

Tricycle: Again, the centrality of taking refuge, in particular in the sangha . . .

Sangharakshita: I think the FWBO has a role to play within the wider Buddhist context insofar as it might help remind people of the importance of something that is there in their own tradition—whether Theravada, or Tibetan, or Japanese, or Zen—but which they tended to neglect. In as much as you are Buddhists, you are essentially people who go for refuge. It is vital, within the context of your own tradition, to give primacy to that going for refuge. You must always try to deepen your experience of going for refuge. And this is not done only through meditation. It can be done in all sorts of ways.