His Holiness the Dalai Lama is the spiritual leader of Tibet, the winner of the 1989 Nobel Peace Prize, and a source of inspiration to Buddhists and non-Buddhists worldwide. Now his remarkable life story is available in a surprising format: a graphic novel.

Man of Peace: The Illustrated Life Story of the Dalai Lama of Tibet, is the product of a collaboration among five artists and three writers, one of whom is Robert A. F. Thurman, Jey Tsong Khapa Professor of Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Studies in the Department of Religion at Columbia University and president of the Tibet House U.S., a nonprofit organization dedicated to the preservation and promotion of Tibetan civilization that he cofounded in 1987.

Thurman, a longtime friend of the Dalai Lama’s, sat down with Tricycle contributing editor Dan Zigmond at Tibet House in July to discuss Man of Peace. They spoke together in the cultural center’s library while staff and volunteers prepared to celebrate the Dalai Lama’s birthday later that evening.

How did this book come about?

William Meyers, who initiated the project, had a long and checkered life. Since I knew him, he was working as a book designer and a typesetter at Columbia Press. His first wife was given three months to live or something like that. Somehow she met the Dalai Lama—I guess he picked her out of a crowd to have a chat with him, and she told him her story. He invited her to come to Dharamsala to consult his physician, maybe to extend her life a little bit. He didn’t promise any big thing. But she went there, and actually, she lived three more years.

During those three years, under the treatment of that [Tibetan] physician and out of gratitude to His Holiness, she started collecting thoughts and reading biographies and memoirs of members of His Holiness’s family to try to make a comic book for children. It was pretty much like Tin-Tin in Tibet.

Then she died, and William remarried after some years. At some point, maybe 15 years ago, we met. He was around Tibet House and came to my classes and things, and he brought up to me that this was a project he felt his first wife had commissioned him to finish on her deathbed.

I immediately thought it was a great project and started consulting for him. Then I scraped together a little money. William and I moved it forward very slowly, and we got a good friend, a Tibetan thangka artist to start making some pages. But it was way too slow, working with volunteers. Then finally someone gave us a nice grant a couple of years ago, and we were able to hire the Legend House Studio of the graphic artist Steve Buccellato. And he got a team of four other artists, and they went to town.

We managed to save enough out of that grant to be able to pay for the first printing—it was an expensive book to produce because of the color and so on. We were supposed to finish for His Holiness’s 80th birthday, but we were a year late.

What do you think is unique about this graphic novel? His story has been told many times before.

The escape from Tibet had been told, although there are a lot of details in there that people don’t know, too. And His Holiness himself has told the story, but he would never show himself as a hero. He tells it as he sees it from his own point of view: “Oh well, I talked to so-and-so, who was like that. I did this, and then that happened.” But he never paints himself as doing something heroic, or brave, or speaking truth to power, or whatever it is. He would not portray himself like that, and we do. We uniquely show how he is this era’s “man of peace.”

He might also be reticent about his vision about Tibet. At Harvard, I did a TV interview with him and asked him what Tibet’s role in the modern world would be, how he saw its economy, for instance. He kept saying, “I don’t know, I don’t want to talk about it,” I guess because he didn’t want people to think that he was sitting scheming what to do with the country or something like that. Those were the early days, 1981, long before the Nobel Peace Prize. It was only his third trip to the US.

Then he said, “Switzerland of Asia. We have all this great medicine.” His Holiness loves the medicine tradition, and he takes Tibetan medicine himself regularly as a preventative measure. Then he said, “We have all these great mineral springs, we have beautiful landscape, clean air, there’s hiking, and so on. So at the end we show his vision of the medicine land, which he himself wouldn’t have written about. I’ve never seen him make another public statement about that.

What is the most essential piece of his thinking that you wanted to get across?

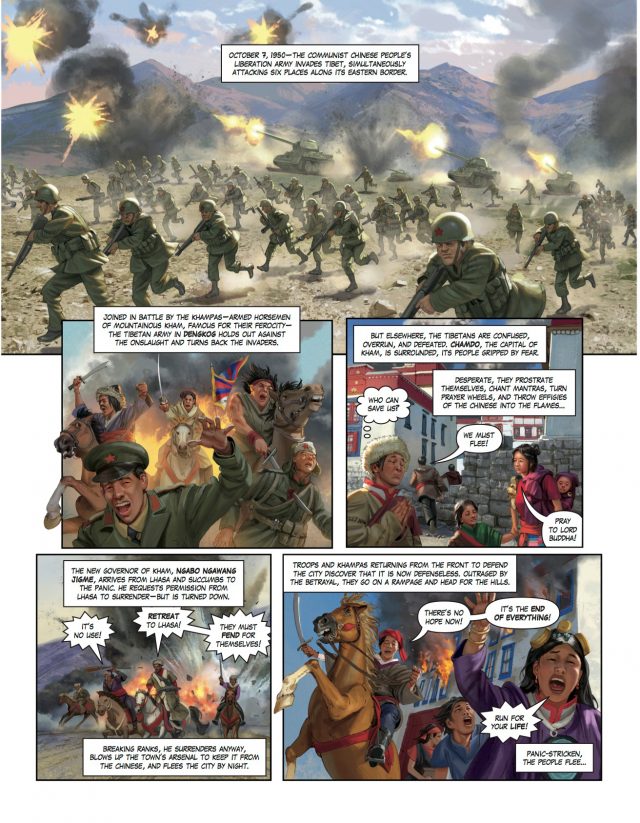

This idea that this man has been going around the world trying to stop a genocide, nonviolently. It’s basically like America in the 1890s. There’s nothing specifically Chinese about it—it’s a typical imperialist, colonialist thing. They’re not the arch evil of all time. Americans, Russians, French, Brits—everybody’s had their nasty imperialist genocides. But it is a genocide, and people don’t really realize that. To tell His Holiness’ story truthfully, one must show how the suffering of his people is in his mind all the time. And yet he’s still peaceful. He has both a principle and practical reason for that. So, we want readers to really get a sense of that.

I feel that his plan for peace on earth through nonviolence is the strategy that we all need. Buddha taught it, and Jesus too, and Thoreau, Tolstoy, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King all put it into effective practice. His Holiness is the one who now carries it on full force. People say, “Oh, that’s very impractical, such nonviolence. Look at how Tibet is. It’s never worked. It’s hopeless.” And I’ve had a lot of people tell me, “Oh, the Dalai Lama shouldn’t say things about politics. He should stay out of those situations. His ideas are simplistic and Pollyanna-ish.” But I don’t think so. I always say, “Well, how are things in the Middle East? Are you happy behind your wall there in Israel? Are the Afghans doing great or what? Is all the violence succeeding? Is it all settled?” I don’t think so.

So you appear in the book a couple times.

We’ve been friends for 53 years. I could appear a lot more!

The first time you’re a monk.

Wanting to be a monk. He made me a monk in 1965, since I wanted to be one so intensely. But it was not my karma. I had been living as a monk since 1962, but I wasn’t formally ordained till 1965. My first root teacher, who brought me to study with His Holiness, didn’t want me to be a monk. He told the Dalai Lama, “Don’t make him a monk. He’s very sincere—he wants to be a monk. But he’s not going to stay a monk.” He was older, very wise, and more experienced with the West at that time. And then by mid-1966 I realized he was right, and I resigned.

Afterwards, I was so poor when I met and fell in love with Nena, but we married anyway and started a family. I began as a graduate student at Harvard in 1967.

During that intervening time I was really frightened and worried [about seeing His Holiness] because I was the first Western monk he made. They put this meeting in the book in a semi-humorous way, [where the Dalai Lama says] “Uh-oh, here comes my monk! Where’s his robe?” And that was just William Meyers’ way of compressing a long story. I didn’t want to put that much about myself.

What do you think about your future at this point?

I’m very optimistic about it. I will be formally retired from Columbia as of 2019. That I’m happy about because I can finally travel during key times of the year in India in the northeast, since the nicest time of year is in autumn, weather-wise. And I’ll be able to go to some teachings and things that I’ve missed. His Holiness is in his sunset years, although he has promised to live past 100. And pledged me to do so also. I don’t know if I can, but I think he can.

Tibet House is still not officially endowed, which was our job, and we’re supposed to make sure we finish work on it, so I’m hopeful we’ll be able to do that.

And I’m hopeful that within Chinese President Xi Jinping’s second term, if—knock on wood—all goes well in the next 12 months, we’ll have a new Politburo, which oversees the Communist Party, with all of his own people and none of the hardliners who think if you give Tibetans an inch, they’ll demand independence and break away and all this nonsense. There’s no possibility of them doing that, and they wouldn’t even really want to do that if they were treated better.

There definitely is a demand for true autonomy where they can have their Buddhism, though: they can invite their friends back and forth to Tibet and set up teaching institutes around their monasteries or whatever it is. Definitely they want that. And maybe, hopefully, in the second five-year term, after 2018, when these people are fully installed, then Xi Jinping can start trying to [make that happen].

Do you think there’ll be a 15th Dalai Lama?

Oh, sure. No question.

No question?

I mean, Dalai Lama told me not to talk too much about it the one time we debated it. I argued strongly that His Holiness shouldn’t completely resign. He should be a constitutional lama like a king of Norway or Sweden. But he said, “no, I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to be a prisoner like Lady Di!” She was already dead at that time, but he remembered it. It made an impression on him.

I lost that debate; he refused to even consider it. He said, “no, I really want to get out.” So then when I gave up, I said, “Well, fine, but don’t worry. Your successor will be drafted by the Tibetans anyway! Just because one elder Dalai Lama feels tired of being the head of the country doesn’t mean that they’re going to let you off-duty!” He laughed and told me to drop it.

Why did you want him to remain head of state?

My reasoning is because of democracies that you see become mammonocracies: rule by money, worship of money. And then the officials and the parliamentarians are more or less for sale. Somebody should be not for sale in a country. That person should set an example. Then [people running for office] will have to be more competent to win. That was my argument.

But this idea that he may end the whole lineage with himself. Do you think that’s possible?

No, no. There’s no question. He has a big prayer: “As long as there are living beings suffering, I will remain, will come back again and again . . .” There’s no question he comes back. But he has chosen not to hold political office in the future. That’s what is meant by “last Dalai Lama.” It re-defines his “Dalai Lama” reincarnation as purely spiritual, with no further political responsibility. That won’t stop him from being “Dalai”—an ocean of wisdom and compassion—and a “Lama,” a true teacher who cannot be avoided!