I hadn’t been in Dharamsala, India, more than two days before I started dreaming about where to go next. While the rain overflowed the sewers and wet cows bunched under the running eaves of the bakery next door, I sat with the other travelers around the wood stove at the Green Restaurant, eating dense slabs of Tibetan bread and butter, drinking mug after mug of ginger lemon tea, and discussing the options. Kullu, Manali, Gangotri, Kathmandu…the names, repeated like mantras, hung shimmering and hopeful in the smoky air, conjuring visions of mystery and magic (as the word Dharamsala had, just a week before). At night, alone in my room, I lit amber incense and consulted the oracle of theLonely Planet, whose every page hinted at a new adventure. I spread out my atlas and traced, with a cold finger, the dotted gray ribbons of railways, the bright yellow bands of roads.

It was six years ago and I was four months into a six-month trip around India, researching ashrams, monasteries, and pilgrimage sites for my guidebook, From Here to Nirvana. Planning the trip, it had sounded glamorous: an unending stream of spiritual peak experiences. It even sounded like that in my postcards home: “Dear Friends—Here I am in Dharamsala, attending the Dalai Lama’s teachings on the ‘Lam Rim Chen Mo,’ or ‘The Great Book on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment’. . . .”

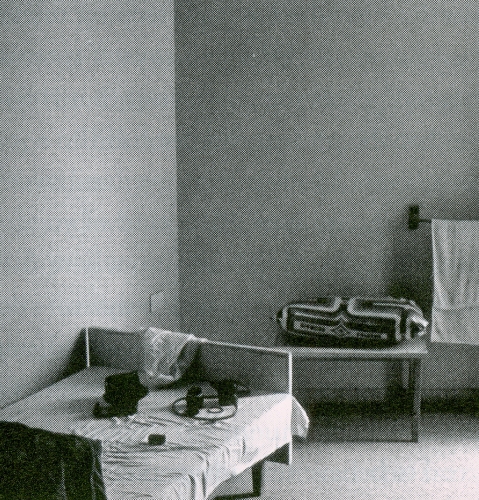

But the reality of the experience was more like this: I was writing my postcards in an unmade bed, surrounded by a litter of earplugs, crumpled receipts, unwashed underwear, and squashed acidophilus capsules scattered from a ruptured ziplock bag. It had been raining hard for four days; the mountain peaks were erased by clouds, and my soaked Kashmiri shawl permeated my already mildewed room with the smell of wet sheep. My hands were so cold I could hardly hold my pen. To keep warm, I was wearing most of the clothes I had with me: long underwear, all three pairs of socks, khadi shirt, cotton Punjabi suit, wool sweater, and a neon pink ski cap I just bought the day before at Stitches of Tibet. That morning I had overslept and missed the sunrise long-life puja for His Holiness the Dalai Lama, because the night before I had stayed up too late: I’d been lonely and cold, so I had used my portable electrical coil to heat enough water for a hot water bottle, bought a Cadbury’s dark chocolate bar and a secondhand copy of Rudyard Kipling’s Kim to keep myself company, and stayed up past midnight, snuggled up to warm rubber, reading about someone else’s spiritual adventures in India.

As I made my spiritual pilgrimage around India, I had noticed this phenomenon again and again: Whenever I arrived at a new destination, jagged reality ripped a hole in my silken fantasies. The ancient temples might be there, as the guidebooks promised, the Shiva lingams, the orange-robed sadhus, the sacred river. But rickshaws belched out fumes in the urine-scented streets; the holy men chased me down the street, rattling their tiffin tins and demanding that I buy them chai; and I’d open my knapsack to find that my toothpaste had ruptured in my toiletries kit, where it was steeping my foam earplugs in a minty ooze. So I’d catch myself retreating to plans and imagined pleasures, believing that the future held a promise that the present did not fulfill.

It was a lesson I had to learn over and over: that a spiritual pilgrimage is, after all, a kind of yoga. And yoga is ultimately not about getting anywhere different. It is about fully being where you already are—embracing the mundane details of your body, your mind, and your life, and tranforming them through the power of your presence and attention.

We tend to believe that a yoga pose is a final destination, that when we can finally put our palms flat on the ground in a standing forward bend, or touch our feet to the back of our head in a deep Cobra, something magical will occur. We will finally have arrived somewhere special. But when the long-sought goal is reached, we find that we are exactly where we have always been: at home in our own familiar bodies, our own unruly minds. And the magical goal has suddenly receded into the distance again: If we could only get our hands underneath our feet, arch our spines a little deeper…

On my yoga mat, I have had to learn that the journey itself is the final destination. I have had to learn to love the roadblocks and detours in my body: the weak or frozen muscles, the locked joints, the pockets of anger and grief and despair. I have had to learn to slow down and savor my body exactly as it is, trusting that there is nowhere better to be. And on my journey through India, my practice was just the same: Could I embrace the gritty, often tedious details of life on the road as expressions of all-pervading Spirit? Could I let what was actually happening be enough?

As a guidebook writer, my job was to pillage a place of its secrets. I’d arrive armed with notebook and pocket tape recorder, determined to ferret out hidden spiritual treasures. But magic, I learned, takes time to reveal itself; and places, like people, resent being used. Approached too aggressively, a new town became dense, impenetrable; it clenched and resisted my entry, like a body pushed too far, too fast into a yoga pose. It needed to be seduced slowly and gently, with the sense of infinite time to spend on the encounter; only then would it open and welcome a visitor in.

Again and again, I had to learn to receive a place rather than assault it—to slow down enough to follow subtle signs and chance encounters. When I actually managed to do it, a place would begin to reveal itself, like a Polaroid developing in my hand—unveiling its hidden beauties, its quirky charms, its sad and triumphant stories, more enthralling than anything a guidebook could possibly have promised.

That anonymous coconut vendor on the corner in Tiruvannamalai, who lopped off the tops of green coconuts, balanced in her palm, with a few deft chops of her machete, and handed them to me with a plastic straw—when I got to know her, she turned into Jyoti, whose husband drank and whose milk cow had died the year before with a cancerous lump in its groin. She was saving her coconut money to pay school bills for her thirteen-year-old son, who dreamed of being a computer programmer.

The Tibetan nun who poured me butter tea at the Dolma Ling nunnery had walked through the mountains from Tibet to India just three years ago; under her robes, she still had the scars from torture with a cattle prod in a Chinese prison. As she handed me the tea, her face lit up with a smile of pure delight, as if I were a friend she’d been waiting to see for months.

And the dirt path out behind my hotel in Dharamsala that looked like it led to an outhouse—I followed it round a corner, and into a forest of pine trees and rhododendron, bursting with crimson, improbably large blossoms. I wound my way up and up, over granite and pine needles, calves aching, lungs burning, chasing the clean, fresh smell of snow. The song of running water led me into a shadowed valley, over mossy tree roots, through a tangle of brittle bracken, till I scrambled over smooth granite boulders and sat in the spray of a hundred-foot waterfall that crashed into a gray-green creek. I lay on my back and stared up at the jagged line where mountains meet sky, and I thought of the question that had obsessed me that morning: “Where should I go next?” And I started to laugh as the waterfall answered: “It doesn’t matter. You’re already here.”