Butoh [bu-tō], often translated as “Dance of Darkness,” rose out of the ashes of post-World War II Japan as an extreme avant-garde dance form that shocked audiences with its grotesque movements and graphic sexual allusions when it was introduced in the 1950s.

Indeed, many people are still disturbed by the intensity and rawness of Butoh. Performers move awkwardly and slowly with shuffling steps, looking more like zombies than dancers. Their faces twitch; their bodies shake with tension. The acknowledgement of Butoh as a significant art form is now firmly established in Europe and America in addition to Japan. At the same time, the “practice” of Butoh has grown as a way, like meditation or yoga, to gain self-awareness and wake up.

Though not directly connected to Buddhism, Butoh shares the tenets of selflessness, transformation through changes of consciousness, and above all, compassion. “Its grotesque elements do not constitute the core of Butoh,” wrote the dance historian Juliette Crump in the 2006 essay “‘One Who Hears Their Cries’: The Buddhist Ethic of Compassion in Japanese Butoh.” “Rather, it is the basic Buddhist value of compassion that inspires Butoh’s content and powerful expression.”

No one has done more to bring Butoh to America than Vangeline, the founder and director of the Vangeline Theater and New York Butoh Institute. Born in 1970, Vangeline moved from her native France to New York when she was 23, where she worked as a jazz and cabaret dancer until 1999, when she saw a performance of the Sankai Juku Butoh company at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

“It was like having an out-of-body experience,” Vangeline recalls. “I stopped everything I was doing and began to study Butoh.” She studied for five years with the Mexican Butoh master Diego Piñon, who had been inspired by the pioneering Japanese dancers to introduce Butoh to his country. She started the Vangeline Theater and New York Butoh Institute in 2002 and has been performing and teaching Butoh ever since.

Her dancers perform several times a year in New York City, often with visiting Japanese masters like Atsushi Takenouchi or her own teacher, Tetsuro Fukuhara. Vangeline also has used Butoh to call attention to environmental and social issues in presentations such as “Wake Up and Smell the Coffee” in Brooklyn last April, where the performers danced above 1,500 discarded coffee cups.

In addition to working with her students in New York, Vangeline has also brought the transformative power of Butoh to the LBGTQ community, as well as to the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for Women and other New York City-area prisons. She has been in residence at Princeton University, and conducts frequent workshops at Zen Mountain Monastery in Mount Tremper, New York, where the “Dance of Darkness” offers participants another way to experience the need for compassion in a suffering world. Over dinner one night, she talked to me about the art and practice of Butoh.

Butoh means “Dance of Darkness.” What does that darkness mean to you?

I think of it as the dance of the unconscious, an expression of what we have not been able to express, of thoughts and feelings that are buried deep inside, beneath our conscious awareness. In Butoh, we try to bring those thoughts and feelings to the surface, to confront and transform them.

Is that why Butoh dancers sometimes look like zombies?

Death has been a theme in Butoh. The gestures are often grotesque, and go back to its beginning, in the wake of Hiroshima. One of the founders, Tatsumi Hijikata, said Butoh is a dead body standing up, and talked about the dead dancing with him. Kazuo Ohno, the other founder, was a prisoner of war and saw many of his comrades die in front of him, but he embraced this with compassion, even love. Hijikata was the fiery heart of Butoh while Ohno is often considered its soul. Even though the darkness is present in his dance, he is walking toward the light.

What is your day-to-day Butoh practice like?

Hijikata said Butoh is not dance, Butoh is existence. For me, Butoh is a way of life. I dance every day, I perform, I teach, I’m writing a book about Butoh, and I run a nonprofit Butoh dance company. I try constantly to facilitate awareness and an exchange of information because Butoh is so misunderstood as an art form.

Why is Butoh misunderstood?

There are a lot of reasons: it comes from another culture, and the aesthetics of Butoh are sometimes so distorted and strange. But I think the main reason is because it elicits fear, because it deals with the dark side of human beings and reflects things that people don’t want to face.

How do you choreograph a Butoh performance?

The term “choreography” is problematic for Butoh. Choreography in the West implies a set sequence of movements. Butoh is very different. The timing and movements are not set. In Butoh, we want to uncover movement, not tell the dancers what to do. Instead, I give them a task, something to do physically along with a visualization.

What’s an example of a task you might give your students?

I might tell them to turn slowly and imagine that a stick is growing out of their temples, that they can feel it growing longer and becoming heavier as they move. The image is just a stimulus to trigger memories, associations, imagination. Each person experiences it differently and moves differently, but there’s resonance between the dancers. We connect to everyone and everything around us.

Historically, isn’t Butoh related to Japanese Noh theater and Kabuki?

Yes and no. Noh is a traditional form of theater and Kabuki is a form of opera, but both are based on dance and use very stylized gestures to convey emotions. In that way, perhaps, Butoh is similar. But Butoh was also a complete break from traditional art forms like Noh and Kabuki. Hijikata encouraged his dancers to study traditional Japanese forms in order to break them.

Do you see a connection between Butoh and Zen practice?

People are looking for stillness in both Zen and Butoh. And both have to do with acknowledging emotions like anger, fear, and sadness, and letting them go. The difference is that in Zen you accomplish this by sitting, whereas we let them go through movement. We enter all these charges in order to transform them.

Charges? Electrical charges?

Yes. Anger has a charge, sadness has a charge, fear has a charge; but we only distinguish one from the other in our minds, with words. To the body, it’s just energy. It doesn’t have a name.

Is Butoh a way of achieving happiness?

I think it’s about achieving transformation. People said that when Ohno danced he radiated joy. But I feel he touched people because he was able to access the memory of suffering. Maybe happiness comes from acknowledging suffering, accepting it, and having compassion for it. You cannot practice Butoh long-term without developing some sense of compassion, because you confront so much pain in yourself and in others.

You were recently in Japan. Is Butoh different there?

The Japanese are much more intensely conscious of body language and physical gestures than Westerners are. How low do you bow? Who goes through the door first? Japanese Butoh dancers have used a lot of that Japanese body language as a jumping-off point in their work.

What were you doing in Japan?

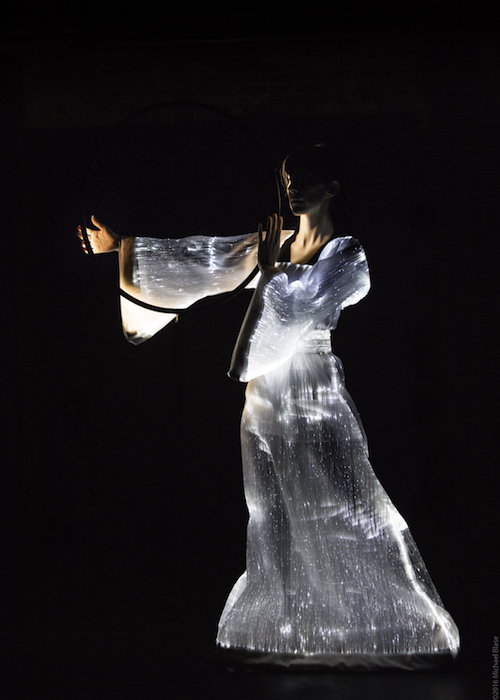

I was with my teacher, Tetsuro Fukuhara, mostly doing intensive practice from 4 a.m. to 8 p.m. But we also visited the Japanese space agency. He’s been working with scientists there to understand the effect of zero gravity on the body. Fukuhara dances in a big tube that’s suspended above the ground. It’s made of Spandex, so your body feels like you’re walking on the moon when you move around in it.

You’re also interested in Butoh and neuroscience. What are you hoping to find out?

I grew up with science. My father is a scientist, a paleontologist. In a way, the relationship between science and Butoh is natural, because in Butoh you become intimately aware of physiology and anatomy. But I’d like to know what goes on in the brain. I think Butoh dancers enter an altered state of consciousness, somewhat like meditation. Neuroscientists have studied the brain waves of Buddhist monks while they meditate. I wonder if we’d observe the same kind of brain waves with Butoh. It would also be interesting because Butoh evokes so many raw emotions—we tap into violence and aggression, and it would be interesting to see if that’s reflected in the brain. It would even be interesting to measure the brainwaves of the dancer and the audience watching the dance to see how they relate.

You teach Butoh to prisoners. Are they different from your regular students?

One difference is that people in prison don’t have any room for dishonesty. Their dancing is so deeply truthful that it’s always a lesson for me to watch them. Otherwise, I don’t really see much difference. The conditions are different—they’re in prison and we’re not. But we’re all prisoners of something. They are literally prisoners, but people can be imprisoned by other things. We can be imprisoned by our past, our possessions—even our freedom. Some people come to my class and are almost paralyzed by their freedom of having so many choices.

How do you imagine Butoh will change in the future?

It’s an interesting time in the development of Butoh. Right now, there are more non-Japanese Butoh performers than Japanese dancers, like me—I’m born French, living in America, and teaching Butoh in the Japanese tradition. I think the 21st century is a time of hybridity and global connection, and that Butoh is becoming an international art form. This raises questions about cultural ownership and identity, but my teacher, Tetsuro Fukuhara, and other Japanese teachers think that the encounter of Japanese Butoh with the West is fascinating. Their attitude is that Butoh belongs to everyone.